Avarice and Alienation: Jewels of the Romanoffs

Avarice and Alienation:

The Jewels of the Romanoffs

Not long ago, by chance I ran across Associated Press accounts dated July 24, 1929, with one titled "Americans Eager to Buy Crown Jewels, Gasp at Price," regarding an unofficial American delegation touring Russia on a fin-de-décennie shopping spree. As the story in the Atlanta Constitution reported, "Although members of the [delegation] today purchased many thousands of dollars worth of paintings and other art objects from the soviet government, they came to one place where even American wealth was powerless." The Americans were allowed to view a portion of the Russian crown jewels, which were then appraised at $264 million, including Catherine the Great's coronation crown and the 190-carat Orloff diamond given to her by her former lover of that name. The Russians, being strapped for cash, wanted "to convert these gems into plough shares, locomotives and tractors." But when the Americans expressed interest in purchasing, they were told that the cheapest item would cost $1 million. That soured the deal, but it may not have killed it.

Intrigued, I did a survey of major newspapers regarding the crown jewels, beginning with the 1917 revolution to see if there had been such offers before. There had, or rather there had been kinda-sorta offers reported in the press. The jewels, or portions thereof, were forever (and somewhat contradictorily) being stolen, sold, smuggled, pawned, publicly displayed, and privately hoarded. What follows are some of the highlights that caught my eye, and I quote liberally from the wiggly words of these organs that for many would have been their only source of news on the subject. This is not a comprehensive account, but rather the sort of thing that the papers' browsers would read over the years.

We begin with coverage of the crown jewels during the first five years following the removal of the Romanoffs, 1917 to 1922.

— David Hughes, September 2015

Part 1

No Sale

As early as May 16, 1917, just two months after the start of the Bolshevik revolution, the Russian crown jewels were being discussed by columnist Marquise de Fontenoy (Marguerite Cunliffe-Owen), a Kitty Kelly of her day. No stranger to empire and royalty, she led off that day's column with, "If the socialist and ultra radical element of the provisional government at Petrograd has its way some of the very finest jewels in the world will shortly be placed on the market, for its leaders are anxious to convert into cash and, above all, get rid of the magnificent crown jewels, so as to be able to convince people at home and abroad that there will be no restoration of the monarchy in Russia." Appropriately enough, as described by La Marquise, the royal jewels had a power beyond their beauty. Speculation on their sale, however, was made complicated when the St. Louis Post-Dispatchreported on September 2 that "the Romanoff crown jewels, a hoard which no other collection in Europe can approach for magnificence—have disappeared."

One-stop shopping? This likely is the first photograph ever taken of the Russian crown jewels, from an album issued in 1922, and included in the collection of George F. Kunz, now at the U.S. Geological Survey Library. The album ostensibly was crafted to create interest amongst buyers. Or was it? Click for very large zoom. (Photo courtesy U.S. Geological Survey)

According to the Post-Dispatch account, officials of the revolutionary government in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) were charged with performing an inventory on the jewels in a vault in the Hermitage museum. "It was opened, and apparently every piece was in place, with the exception of a few decorations and minor jewels." Well, not so fast...

The sight which seemed to meet the eyes of the commissioners was the most imposing which the rejoicing eyes of a connoisseur of precious stones and pearls might ever hope to behold. In the midst of the heap appeared to glimmer the Orloff diamond […]. There were more than 40 strings of what appeared to be the finest and largest pearls in the world, outside of India, besides many of the biggest and purest rubies and emeralds known.

But when experts were summoned the astounding revelation came to light that every jewel and pearl remaining in the safe was simply paste and imitation.

The same had been done with many of the masterworks of art that had hung in the museum and Winter Palace. It was surmised that Czarina Alexandra Feodorovna (Alix of Hesse) had spirited the valuables out of the country—likely to her German homeland. She never was really liked, the article said, even by the aristocracy.

Render unto Caesar what is Caesar's

Nine months later, a June 5, 1918 AP story reported on a plot to smuggle the jewels into the U.S. Seized were $150,000 of $2 million worth of jewels, with federal agents being "on the trail of the rest." Two days later, federal authorities removed from a New York safe deposit box $350,000 worth of what were alleged to be Russian crown jewels, according to the Boston Daily Globe. But as late as May 2, 1919 a Post-Dispatch editorial asked, "Where Are the Russian Crown Jewels?", mentioning the Orloff diamond once again. "If the Russian jewels are in Hesse-Darmstadt"—the "ancestral seat" of the czarina—"they may fall into the hands of the German revolutionaries; if in Russia, into the hands of the Bolshevists. In either case, it is possible they may be broken up and sold and the jewels that once adorned the Princes of an imperial line may eventually glitter on less aristocratic fingers in London, New York or San Francisco." Just who deserved ownership of the jewels is a theme that would sounded over the years.

Market Mess

A July 29, 1919 article in the Washington Post, regarding the global diamond market, dropped this little tidbit: a Chicago importer just back from Europe was told by Russians that "there was a big demand for the gems in their country despite the chaotic condition of finances and society there. They said that at least $200,000,000 worth of diamonds had been taken out of Russia by the exodus of the noblemen after the bolsheviki came into power." And this didn't include the crown jewels—still missing and worth millions. (The article's market details are of interest: American demand for diamonds couldn't be met; Japan, Argentina, Germany and Austria were big buyers; Brazil had taken up production from faltering India; returning World War soldiers were thought to be heating up the market as they contemplated marriage.)

Three months later, on October 16, several papers including the Atlanta Constitution reported, "Crown jewels of Russia in possession of Prince Youssoupoff, in whose palace in Russia the notorious monk Rasputin was killed, have been stolen from his flat in the West End, of London. The theory is that the theft was the work of bolshevists who traced the crown jewels to England, burgled the flat of the temporary possessor and intend to send them back to Russia to swell the soviet's depleted coffers."

Diamonds from the Romanoffs were back in the news in mid August 1920 when customs agents in New York seized 131 pristine stones intended for Ludwig Martens, "self-styled Soviet Ambassador to this country," as reported by the Post-Dispatch August 13. Government officials theorized that the "loot" was to be sold in the furtherance of Bolshevist propaganda efforts here. But Assistant U.S. District Attorney John Walker laughed at the notion, as did Martens, who said that the crown jewels were under lock and key in the care of the Soviets, per the New York Times the next day.

On January 16, 1922 the Times had it "on good authority" that German war profiteer and politician Hugo Stinnes had the crown jewels in his possession. "They have been 'pawned' to him for 60 percent of their 'estimated value,' an amount that is kept secret."

Two months later, the Los Angeles Times reported on March 12, 1922:

South African newspapers in close touch with the diamond trade state that $10,000,000 worth of stolen Russian diamonds were thrown on the market in the months [sic] in 1921, and the crown jewel collection of Russia, was particularly rich in diamonds.

The diamond production industry has been seriously disturbed by the large number of these gems coming out of Russia, but now the situation is reported as more stable. Some South African mines that stopped producing to await a demand for their stones are at work again.

The article then quotes Los Angeles gem expert W. C. Shaw, who said he'd possessed two snuff boxes from the royal collection.

These boxes have gone to swell the collections of American connoisseurs.

Mr. Shaw explained that while very little is known of the fate of the Russian crown jewels, agents of the soviet government are known to have sold jewels in Turkey, Holland and other places.

"Jewelry of wonderful workmanship," he said, "has been sold by peasants, in some cases, for ridiculous prices. A piece that was worth $100,000 has sometimes been sold for $50 in the first trade. […]

"The greatest part of the jewels that have come from Russia lately have gone to London. Many diamonds, however, have been sent to Holland to be recut. There does not seem to have been any fear of pieces being identified. […]

"Moreover, the artistry of the Russian settings enhances the value of the gems. The niello work, patterns of black alloyed metal on white, and the beautiful enamelling are too much admired to be recklessly destroyed."

Shaw went on to say that 90% of the diamonds in old collections, like that of the Russian crown, suffered from "old-mine cutting," performed by hand, and that they could benefit from machine cutting in terms of brilliance, even with the loss of about 20% of material in the process. Shaw said that the Russian crown collection was considered the most tasteful in the world and, excepting for pearls, probably the finest. "The oriental strain which the Russians inherit from the Tartar invaders accounts for the Russian love of jewels," he said. "It is a common trait in peasant and prince. The Russians of all classes have a way of saving their money by investing in jewels, and the crown collection represented the greatest expression of that Russian trait."

The Los Angeles Times then provided a list of some of the 1600 objects in the royal collection: "golden goblets, innumerable gold plates, some encrusted with gems, a chalice cut from a single great amethyst, jewels of famous orders, Tiaras, coronets, necklaces and thrones, all blazing with the sparkle of rubies, sapphires, emeralds and diamonds." And the crowns of the czars, including that of Peter the Great, "brilliantly ornamented with 900 diamonds and had for its piece de resistance a great ruby surmounted by a cross of diamonds." And, of course, the Orloff diamond, which was added to the imperial scepter by Catherine the Great.

On June 11 that same year of 1922, the New York Times itself discussed a postwar "world market flooded by gems." Production of precious stones had slumped during the World War (1914–1918), and just as production was to ramp up, Russians and others saturated the market. "Ruined by the war and Bolshevism, members of noble Russian families, likewise other Russians who had grown wealthy under the Czarist régime, found themselves with no assets of real value except their holdings in jewelry," the Times wrote. "The jewel traders were aghast" when the market was flooded. "They had laid their plans, counting almost entirely on the regular output from the mines; the sudden stream out of Russia swept away all their hopes and brought some of them face to face with ruin." That was followed by a second wave—"and there is danger of still another flood!" That third wave was heralded by a July 14 Times headline, "Soviet Has Thrones for Rich Americans: Also Has Crown Jewels for Sale, but They Will Come High […]."

Up to the present it has been impossible to ascertain exactly what jewels the Soviet delegates brought with them from Russia, but [Soviet diplomat] M. Litvinoff has stated that his Government still has jewels, which have been nationalized, amounting to millions of dollars, and that it intended to make a detail [sic] catalogue of these jewels with photos so that people from all over the world will be enabled to come and purchase them in Russia or buy from the catalogue.

Among the treasures are diamonds from crowns of France, which had long been lost and, as Litvinoff said: "There are even thrones for millionaire Americans, but these will be very expensive, in fact, everything will be expensive."

Czars Catalogue

Six weeks later, the catalogues were issued, as reported in the August 23, 1922 Post-Dispatch. [1] The crown jewels were either to be sold, or pledged for a loan. The gems were estimated to be worth $500 million. Surprisingly, according to the Post-Dispatch, it was writer Maxim Gorky who was "one of the custodians investigating the possibilities of selling the jewels abroad." After being critical of the Soviet government, Gorky had agreed to exile himself in Germany the previous fall. Stateside, feelers were being put out by former Indiana governor James Goodrich, who had been appointed by President Harding to the Russian Relief Commission.

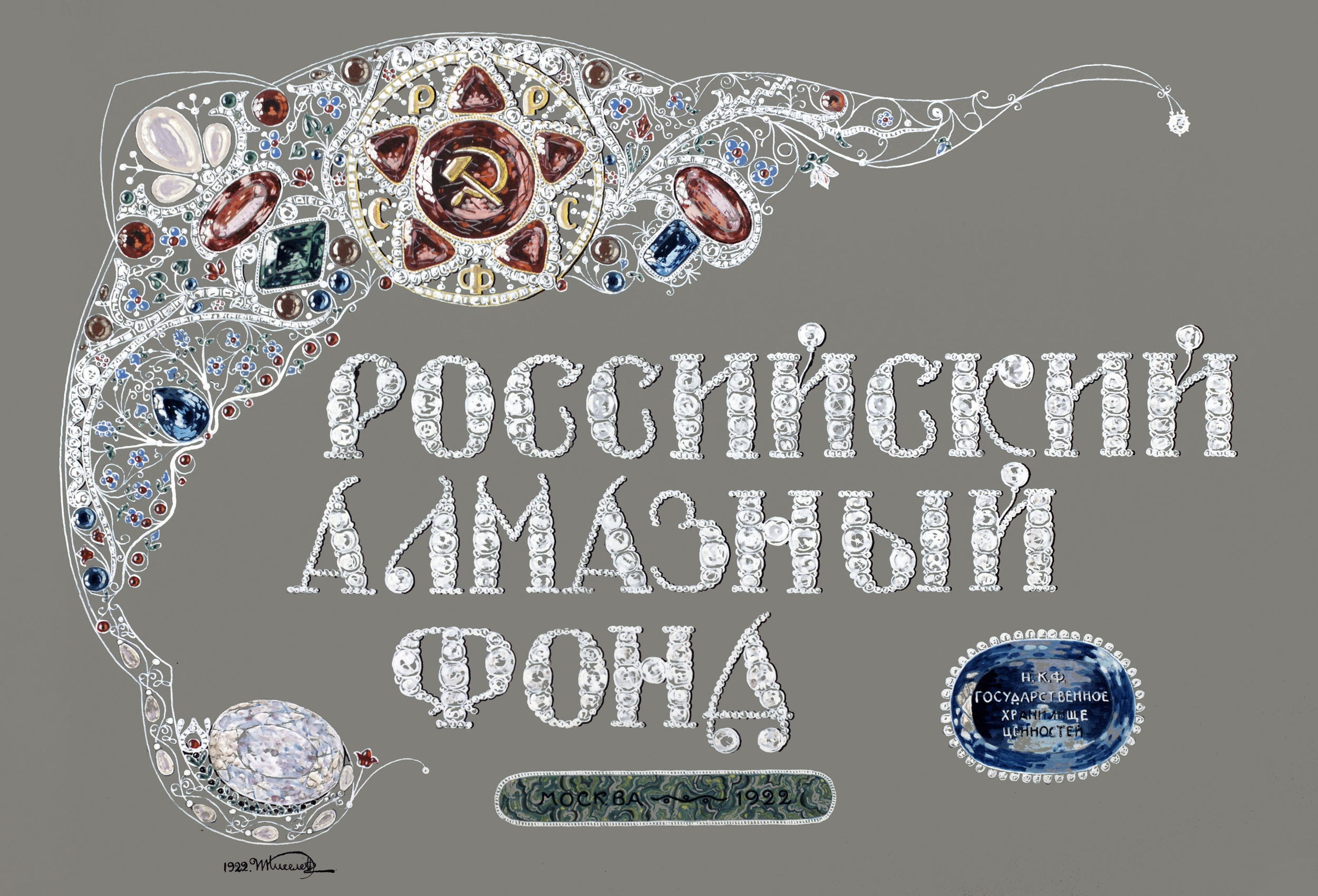

Not Russia's "noblest jewel." Hand-colored title page from the 1922 album, Russian Diamond Fund, from the Kunz Collection at U.S. Geological Survey. It is believed to be the only copy in existence. Click for very large zoom. (Photo courtesy U.S. Geological Survey)

Highlights from the article: "emerald-sprinkled breast-plates"; the "imperial crown bears in the center a glowing rose diamond of 265 carats, surrounded by Brazilian rubies"; "a bouquet of diamonds, colored by some secret process never duplicated, so that they resemble natural roses"; "the Shah seal, with Persian inscriptions which never have been deciphered"; and "a magnificent dog collar of emeralds and rubies." Previous reports notwithstanding, the entire collection "is practically intact," it having been guarded since the czar's fall. As tantalizing as the above descriptions were, the catalogue images were monochrome. They had to be seen in living color.

Seeing Is Believing

Three days later, on August 26, 1922, New York Times correspondent Walter Duranty reported that he and Sam Speewak of the New York World had seen the crown jewels in person, calling the experience an "Arabian Nights vision of the Romanoff treasure." They viewed "diamonds as big as walnuts, rubies, emeralds, bright, blooded or vivid green, large as a pigeon's egg, pearls like nuts set in row after perfectly matched row, platinum, gold and flashing diamonds shimmering like running water with the rainbow colors of a fountain in the sunlight. Over all and through all flash diamonds, rose diamonds, black diamonds, blue, white, yellow, even greenish diamonds, thrilling and throbbing as if alive with inner flames: jewels of Golconda, jewels of Indian emperors for each of whose flashes gallons of human blood flowed like water, jewels of wars of dominion and triumph, jewels without a price or equal in all the known world." (See if you can match a given object in the photo above with its description that follows.)

Lifting a wooden box from a steel chest stamped with the crown of Imperial Russia, the correspondents were shown the real deal: "a square foot of incandescent fire." An unnamed jewelry expert who was present explained, "Thirty two thousand eight hundred karats [sic] of diamonds. […] Please note the unrivaled rose diamonds, twelve of them, averaging thirty karats each. There are fifty big diamonds altogether. The big one which is polished but not cut is Balai, a ruby really, a sort of red diamond. It came from Peking in the seventeenth century and weighs 389 karats." [2] When placed upon Speewak's head, "his face flushed dark, then went ivory pale," Duranty wrote. "For this was the symbol of the world's biggest white empire, the Imperial Crown of Catherine the Great, designed by Pauzier Mauer, jeweler of Geneva, and without peer in his art today." [3]

Catherine II (the Great) desired a contemporary coronation crown, in contrast with the traditional sable-trimmed Cap of Monomakh shown below. If Peter the Great is credited with Russia's cultural and political sea change, Catherine was inspired by her predecessor. In the portrait above, painted by Aleksey Antropov about three years after her 1762 coronation, the empress holds the imperial scepter, not yet set with the diamond she received from her former lover Grigory Orloff. The diadem she wears echoes the design of the full-size, five-pound crown at left. Painting by Alexei Antropov, ca. 1765.

After being shown the Orloff diamond in its scepter setting, the New York correspondents viewed an orb, "an ordlasie gold ball, six inches in diameter, surmounted by a sapphire of 100 carats supporting a diamond cross, 173 carats in all." Next was a "crown of 1,933 diamonds made for Catherine the Great […]. There are 487 carats altogether in this crown, set with diamonds so as to quiver like a mass of jelly." Also shown "was a truly imperial diadem of the style one sees as a laurel wreath gracing the brows of royal Caesars, but here the laurel leaves' weight was as of leaves on the trees of jewels Aladdin saw in the wonder garden beneath the earth. In the centre there was a pear-shaped diamond an inch and a half long of seventy carats with a round stone of twenty carats above it. Of all the jewels we saw this was the most regal." The diadem of Empress Elizabeth, daughter of Peter the Great featured a "huge oblong rose diamond in the centre [that] weighs 125 karats [sic] and is without peer outside the fabled treasures of an Indian Rajah. Its full fire is lost because it is set in a gold locket, which the tradition of the imperial dynasty forbade to alter. Above it there is a row of diamonds as big as a finger nail and below a second row of pear-shaped pendants, of which one is missing."

A photogravure of the Cap of Monomakh, dated to the 13th or 14th centuries. It was used to crown the rulers from Ivan Vasilievich (the Terrible) in 1547 to Ivan Alexeevich in 1682. (Image: Sherer & Nabholz, before 1884, Archives of the Moscow Kremlin Museums)

A diadem fashioned to mimic "ears of wheat," with "fat chunks of diamonds gleaming in the harvest sun" aroused the enthusiasm of the communist officials. "This is the true wealth of Russia," said the head of the jewelry commission, "not platinum, or diamonds wrung from the sweat of workers, but Russia's own natural grain—her noblest jewel." Indeed, crown jewels cannot be eaten, and a month after this article appeared, a Times headline on September 21 warned that "1,000,000 Face Starvation in Russia." (Duranty himself wrote in the October 16 Times that as many as eight million might perish within five months.) More wealth followed, of the gemmy sort: eleven uncut emeralds each an inch long, roughly polished, pierced and dangling from a diamond pendant necklace; the 1.5-inch-long Shah diamond (the "Shah seal" mentioned above?), looking "like the cut glass stopper of a decanter," inscribed in Arabic but otherwise uncut and unpolished; two brooches of diamonds surrounding enormous sapphires, one measuring 1.5 by 1 inches, 250 carats, and the smaller about an inch square, 142 carats, "and deep azure blue"; Empress Elizabeth's neck ornament with rubies that a workman called "big as the signal lamps of a liner," but this was "outshone by an emerald brooch with two huge oval stones like giant green eyes," weighing 174 carats, "and another beneath them as a pendant [of] 226" carats; a Cossack-style suit of 22,000 diamonds weighing more than 5,000 carats; and "two brooches, the first a light water green aquamarine of the Urals as big as the palm of the hand, and the second item a larger Brazilian aquamarine, the blue of sky and sea, both set in diamonds." About these last two, the expert exclaimed, "For such as these men go mad," adding "with an obvious effort at calm," that "the blue stone is over 1,000 carats. We cannot compute its value, for it is utterly unique."

For his part, Duranty felt that the "most beautiful of the lot" was a jeweled snuffbox, "a tabatière of the fifteenth century, probably Italian, of black enamel on gold with perfectly harmonized flowers, sprays and insects on rose, white, yellow and blue diamonds."

No Sale (Again)

If Duranty's sumptuous verbal depictions on August 26 extended expectations that the Romanoff jewels would be sold off, such hopes were dashed the next day by his mouthpiece, the New York Times. "Charles Recht, the legal representative of the Soviet Government in this country, said yesterday that he received no word of any intention on the part of the Soviet Government to sell the vast treasury of gems in its possession, described yesterday morning in a cable dispatch to The New York Times from Walter Duranty in Moscow." Recht couldn't even discuss the gems being used as collateral for a loan.

Nevertheless, the Times reprinted portions of its June 15, 1922 article about a sale in Paris by Cartier of the "largest known emerald in the world," which "once had adorned the neck and shoulders of Catherine the Great of Russia." Pierre Cartier, in the June article, had said that the Russian revolution had brought into private hands many of the world's most important jewels. "I cannot escape a certain feeling of sadness," he had told the Times while holding up the stunning necklace, "at the thought that this historic work must be destroyed and the stones parted with singly. But the last rightful owner is dead and all he has left his descendants is the title." Ironically, it was French emigrants, fleeing that country's revolution, who had sold their jewels to Russian aristocrats; now the tables were turned.

Besides Recht's rejection of the notion of a gems sale, there was some good news in the August 27 article. "The market has since recovered" from the gem glut of the previous three years, "although a general dumping of Soviet treasures would cause a tremendous break, it is believed." In May it had been reported by gem experts that $80 million worth of jewels had been sold to French jewelers by Russian, German and Austrian nobility during those same three years. Others put the figure at $200 million. And many a charlatan was thought to have passed off a bauble or two as having royal provenance. "There exists in Europe a large number of 'easy-money' individuals of suave manner and pleasing address who make it their business to sell gold bricks of this kind," New York Jeweler Julius Wodiska told the Times. "A not unusual performance for them is to burst into tears and tell how the plight of their family forces them to sell their heirlooms."

"Ensanguined stones"

We'll close our look at the fate of the Romanoff jewels during the first five years of Soviet Russia with the following, the New York Times' own supercilious commentary on Walter Duranty's effusive prose regarding the gems, and regarding the Russian workmen's demeanor in the presence of treasure. From the August 28, 1922 editorial:

These jewels have a heightened lustre and brilliance in the contrasting setting they give to the plain, drab, indifferent Bolshevistic régime with which they are now associated. Communist officials handle them with an unconcerned air and with hands that do not itch though they tremble [quoting Duranty] "ever so little" over the crown of the Emperor. A Russian peasant in his smock holds for the moment a sceptre that has lost all but its innate beauty and power. Workmen sit down to their lunch in the midst of this surpassing spectacle with no more avaricious wish—even if this one comes into their thoughts—than that those stones might be commanded to be made bread. and the Soviet head of the jewel commission with careless gesture tosses into its place the "most wonderful and historic stone civilization has known," the diamond that hung before the throne of Akbar the Great, Mogul of Hindustan, under whose mild rule (ending in 1630) India was as well governed as France, Spain, Italy, Germany or Russia. To Akbar every ruby of price was "the magnificent ruby." To the Communist the most magnificent seems to have become the commonplace.

These stones would, heaped together, build such a "cairn of remembrance' as no other collection in the world—remembrance of glory, of romance, of misery and of hideous death; for some are such as the Duke of Clarence dreamed of in his imprisonment in the London Tower, all scattered in the slimy bottom of the sea: "Wedges of gold, * * * heaps of pearl, inestimable stones, unvalued jewels." Some of them lay in dead men's skulls; and in the "holes that eyes did once inhabit" there had crept "reflecting gems." So one cannot look upon these imperial jewels, which the Bolsheviki have guarded so scrupulously, without seeing them all turned to rubies—not, as Akbar's, to "magnificent rubies," but to ensanguined stones.

While acknowledging the bloodshed that comes with empire, the Times is critical of the jewel commission head, not to mention the "peasant," in their refusal to quaver before its emblems, and in their defiance: "that those stones might be commanded to be made bread." This having taken place five years since the revolution, it would be five more years before the 1927 publication of Karl Marx's 1844 unfinished manuscript on the subject of the very alienation exemplified by the workers with whom Duranty interacted. In that famous essay, "Alienated Labor," Marx wrote, "Just as [man] creates his own production as a vitiation, a punishment, and his own product as a loss, as a product which does not belong to him, so he creates the domination of the non-producer over production and its product. As he alienates his own activity, so he bestows upon the stranger an activity which is not his own." If only, the Times suggests, the workmen had felt American avarice, rather than universal alienation.

Part 2

In the second installment of our newspaper survey we cover the years 1923 through 1926.

King Tut in Brooklyn

The year 1923 began with more goofiness from the press, with the New York Times on January 5 claiming: "In the forgotten grave of an American seaman buried in the National Cemetery, Brooklyn, Federal officials expect to find within the next two days some of the Russian crown jewels which are known to have been smuggled into the United States in September, 1920, according to a copyrighted dispatch from New York printed in The Chicago Daily News this evening […]." On the 6th, the Timesreported that "no application was made to the Adjutant General of the army for a permit to open the grave […]. Before going so far as to request the exhumation of the body, the Federal investigators will endeavor to trace the source of the report that the jewels were hidden in the coffin and smuggled into the United States." That same afternoon, an armed guard was posted near the grave of Seaman James Jones, in order to discourage looky-loos.

By the time the coffin was opened, on Valentine's Day, the grave was guarded by a detachment of the Eighteenth Infantry "armed with rifles and machine guns," as reported the next day by the New York Times. The body of Jones, "a humble navy messman," was disinterred. "The Romanoff crown jewels, valued at $4,000,000, […] were not there and one of the most fantastic canards of the war was dissipated." The Times wrote that the "bleak section" of the cemetery that housed Jones's grave had been "a sort of Tut-ankh-Amen tomb to the residents of the neighborhood." William B. Williams, special agent of the Department of Treasury, theorized that the jewels might have been removed from Jones's casket on the ship that sailed to the U.S. from Vladivostok. Williams "corrected an impression that the jewels involved in the story had been referred to by him as the Czar's jewels," the Times wrote. "He had alluded to the jewels as belonging possibly to a wealthy Russian."

Ivan IV, Czar of Russia, wood engraving in Harper's Monthly, 1883, v. 67, p. 99.

Jones had died August 30, 1920, and the government received a letter the next spring from an Edward Roe, care of General Delivery, Chicago, which gave details of the smuggling. Another letter told where Jones's casket had lain during transport. This was evidence sufficient to pursue the disinterment. When Williams first was asked about the smuggling story he wouldn't confirm or deny it, but said, "We are always looking for the Russian crown jewels. They are hardy perennials and bloom the year around. We count the day lost when we don't get some new information about them."

Pearls from a Prince; Bijoux to a Baron?

In January 1924, a remarkable necklace of forty-two black pearls was purchased by Mathilde Gerry, heir and daughter of Richard Townsend, granddaughter of Erie, Pennsylvania mayor William L. Scott, and wife of Senator Peter Goelet Gerry (D-RI)—but not for long; they divorced the next year. The necklace came from the family of Prince Felix Youssoupoff (mentioned above) and was sold via Cartier. "Customs officials said that part of the great collection of jewels brought here by the Prince were still being held by the Government pending appraisal," the New York Times reported on January 25, "but that many of the pieces had been released at the time of the Prince's arrival on the payment of duties." The pearls might have escaped duty had they been strung. "The pearls were recognized as among the most interesting items in the collection." Ms. Gerry bought the necklace for $400,000.

Ten days later, the Chicago Tribune reported from Paris that the Russian crown jewels were to be purchased by U.S. oil baron Harry Sinclair, who had been involved in the Teapot Dome bribery scandal of a couple years before. Sinclair had formed an American corporation for that purchase as well as to obtain large quantities of platinum for the New York jewelry market. Quoting the Tribune article on February 5, the New York Times added, "The price of platinum has been mounting steadily since the war because all known deposits of platinum are in the Ural Mountains and the exports from Russia, which have steadily decreased since 1914, stopped altogether with the advent of the Bolsheviki into power, except for small amounts smuggled out." No follow-up reports on Sinclair's designs appeared in either paper.

Primrose and the Blue Diamond

A storied blue diamond came on the market at summer's solstice that year of 1924. "The Russian gem," weighing in at 43 carats, "according to tradition, graced thousands of years ago the statue of a god in an Italian temple," the New York Times wrote on June 22. It came into the possession of Suzanne Thuillier, "well known at the Nice, Monte Carlo and Cannes casinos under the name of 'Primrose,' and famous for her magnificent jewelry and wealth, [and who] lived for several years in Petrograd." She was given the Blue diamond by Czar Nicholas. "Driven from Russia by the arrival of Bolshevism, Mlle. Thuillier brought the diamond to Nice, where, after heavy card losses she pawned the stone for 200,000 francs." By the time she came to claim the stone, liens in the amount of 200,000 francs had been attached to it. She arranged with jewelers to pay the liens and to offer the stone for sale by a group of Nice bankers. Again, no follow-up reports on the Blue diamond's fate.

Jewels Intact

If the sale of the Blue diamond might have rekindled fears that the Russian crown jewels would be whittled away piecemeal, two reports that summer of 1924 provided reassurance. Writing on June 24 from London, the Christian Science Monitor interviewed MP Sir Martin Conway, who had been an art professor at University College, Liverpool, and Cambridge University. He recently had visited Moscow and Petrograd to investigate the state of art treasures there. (In 1925, Conway issued Art Treasures in Soviet Russia [London: Messrs Edward Arnold & Co.].)

Sir Martin said he found almost all the stories of vandalism and acts of wanton damage done during the revolution to be untrue. The art collections had not only been preserved, he said, but were greatly extended. Even the famous Romanoff crown jewels which have been reported sold, were intact. Sir Martin saw them himself, he said, even held in his hand the famous scepter with the Orloff diamond, Catherine II's crown and many other well-known treasures.

Reporting from Leningrad on July 14, New York Times correspondent Walter Duranty, who had seen the crown jewels the summer of 1922, [4] echoed Conway after visiting the Hermitage and being shown many of its holdings in its "strong-rooms and cellars." "The only 'looting' the Hermitage suffered from the Bolsheviki," Duranty was told by a local Communist official, "was the recent request from Comrade Trotskaya [Trotsky's wife, head of the Federal Museum Commission] that we select 200 of our pictures for the Moscow galleries." The official hoped the Hermitage would become the world's finest museum. Duranty then proceeded to describe the treasure to which he was treated.

The door of an immense safe swung back and there came a veritable explosion of multi-colored light as the rays of the midday sun struck the treasure within. Here, in a prosaic twentieth century strong-room, were amassed the gifts Aladdin's genie of the lamp brought high-piled on the heads of Ethiopian slaves to buy the Emperor's consent to his daughter's marriage to Aladdin—literally the same gifts, for this glittering brilliance was made up of the masterpieces of Oriental goldsmiths from Persia and the lands beyond. Throughout long centuries the rulers of Russia received tribute from or exchanged presents with those of Central Asia. Here was a part, a mere fraction, of their hoard.

Slowly, carefully, piece by piece, golden Persian wine-vessels, their squat bodies and long necks so studded with emeralds and rubies as to be more green and red than yellow, were set on a wooden table in the centre of a room lined with glass cupboards.

Duranty was shown Persian plates from Peter the Great's collection. "You know the Hermitage collection of Persian art is four times larger than those of the rest of the world put together," he was told.

The wine vessels on the table were now joined by a bewildering display of jewel-encrusted golden bowls, mirrors, swords, daggers, cups, plates, stirrups and horse-trappings, ornaments and head-dresses. There was a long-necked golden pot about a foot high set with a thousand square-cut emeralds of an average weight of three or four carats. Around the middle ran a line of emeralds of twenty carats or more each, carved—not cut—flower-like, as the Chinese carved jade. Next to it there were an immense sabre hilt and sheath ablaze with hundreds of close-set diamonds. Others, no smaller, shown with rubies, emeralds, pearls and sapphires. A bowl of pure white Chinese jade glittered with thousands of jewels—red, green, blue and white. There was a dagger ornamented with enamel and gold and set with two huge white diamonds, cut square and engraved with Arabic letters.

Duranty described a gold saddle cup, long-handled, inlaid with a hundred rubies. Even the fly-whisks were set with seed pearls and "fat emeralds."

At last the large table was completely covered with gold and jewels. There were round hats of the finest sable with plumes and rubies and emeralds so thickly clustered upon gold as to resemble red and green flowers. There were gold inkpots and incense burners of seventeenth century Persia embellished with turquoises and eggshell porcelain enamel. There were jade seals and reliquaries whose green was offset by rubies and white jade thumb-protectors of Mongol archer princes, with an inlay of gold and diamonds.

Next, Duranty was taken to a room and shown the contents of a huge steel casket containing a few hundred of Catherine the Great's three thousand snuffboxes. His guide, Hermitage director S. Troynitzki, took one, "plain, flat, oval" and "badly dented on one side," Duranty wrote. "Here you have the weapon," said Troynitzki, "which killed one of Russia's Czars." Emperor Paul I had been struck in the temple with the object by Count Nicolai Zuboff in 1801. It was bequeathed to the Imperial Treasury nearly eighty years later by Zuboff's daughter.

Then came other heavy cases of jewelled ornaments, canes, watches and notebooks of Russia's rulers. Imagine a green dove nearly two inches long by half an inch wide with a diamond olive branch in its mouth carved from a single Colombian emerald, 300 carats in weight, and presented to the Romanoff dynasty by a Portuguese king. There was a tortoise shell cane belonging to the Empress Elizabeth, whose golden handle contained a diamond-studded watch and music box, which still plays a delicate old-fashioned air.

Before ending with a description of "score upon score of gem-bedecked watches," Duranty described an Easter egg—not Fabergé, but beautifully crafted.

And there was an Easter egg of gold and enamel and diamonds which the peerless jeweler Pausier of Geneva [5] presented as a surprise to his royal patron, Catherine the Great. On top there is a tiny watch which still keeps perfect time. The sides open to show the golden boxes for rough [sic], powder-puff and face-patches. The bottom unhinges to reveal a little box of pencils and a note-book.

Seven months after Walter Duranty's sumptuous description of the Hermitage holdings, the New York Times reported on February 19, 1925: "Some of the Crown jewels of Russia were recently sold publicly in an open-air market on a Sunday morning in the East End of London, according to evidence given today in the trial of Joseph Betts for burglary." Betts said the jewelry in his possession was not stolen, but had been bought by him at Duke's Place in the central ward of Aldgate in London. Hundreds of dealers—sometimes as many as a thousand—would give Sunday shoppers a lot to choose from, according to Betts. There were no further reports on the trial in the Times. But the next day, both the Wall Street Journal and Washington Post reported that "part" of the Russian crown jewels had been sold for 500,000,000 lire in Paris to the Banca Commerciale Italiana, having been offered by the Soviet government.

Five weeks later, on March 29, the New York Times wrote from Paris that a Soviet envoy had arrived there "on a mission to negotiate the sale of the remainder of the diamonds that had been stored in a secret underground chamber of the Kremlin." The stones were worth about $500 million, but that likely was inflated. Yet, eight of the article's nine paragraphs discussed a litany of hoaxes, concluding, "The theory is that the sales abroad of alleged Czarist treasure represent nothing but loot and that the Soviet Government has no intention, for the present, of disposing of the treasure that came to it through the sequestration of imperial or Church property."

Back in the old country, Soviet agents on June 27 found a secret stash in the former home of Prince Youssoupoff. Associated Press reported that the loot was found in a steel vault concealed behind a brick wall. "They consisted of hundreds of gold, silver and platinum articles of great beauty, many of them adorned with diamonds, pearls, sapphires and rubies." The house had been turned into a museum, and its caretaker and janitor received a reward for helping to find the treasure. "Among the articles found were two gorgeous necklaces weighing a pound and a half each and consisting of a multitude of diamonds and rubies.

Cross and Gospel. Gift from Czar Mikhail Feodorovich (1596–1645). In the vestry of the Assumption Cathedral in the Kremlin, 1911. Following the 1917 revolution, churches across Russia had their holdings transferred to the Soviet treasury. (Photo: Prokudin-Gorskiĭ, Sergeĭ Mikhaĭlovich, 1863–1944)

Whetting the Appetite

On August 30, 1925 the New York Times published a lengthy article by the aforementioned S. Troynitzki, director of the Hermitage Art Gallery, in which he provided highlights of Russian crown jewels, which had been assembled in the National Museum. While it gave more historical context regarding the collection, Duranty's 1922 description covered roughly the same ground. Less than a month later, on September 23, a thief who appeared to have secreted himself in the Hermitage treasure room made off with a snuffbox, a fan, and other small objects that contained 108 carats of diamonds and emeralds. The jewels were estimated to have been worth 250,000 rubles, but the thief and/or accomplices unloaded the stuff for 4,500 rubles, as reported in the New York Times on October 6.

On December 12, Associated Press reported that representatives of the Soviet government would visit the United States regarding a "sale of surplus articles from the old imperial collection of jewels." The article mentioned that a just-completed appraisal of the entire collection came in at about $250 million, but did not reflect "any historical or sentimental value the articles may possess." Catherine II's famous crown was valued at $52 million; her scepter with the Orloff diamond at $30 million. The gold and diamond imperial emblem, containing a 157-carat sapphire was valued at $24 million. Two of the Empress's coronets, each set with a thousand carats of diamonds, were appraised at $4 million apiece. The Shah's diamond, which Duranty had likened to a glass decanter stopper, was valued at $14.5 million, and a 258-carat Indian sapphire at $11 million.

By January 31, 1926, Associated Press was reporting the collection being worth $264 million. "Soviet Russia is ready to turn her crown jewels into American plows, tractors and machinery." AP quoted one high-ranking official as saying, "We want to turn the glitter of our 25,000 carats of diamonds into the glitter of American steel." Continuing, "The Associated Press obtained today the first complete and accurate description of the regal emblems from official sources. The jewels date from Peter the Great to Nicholas II. They comprise 406 separate pieces of jewelry. The total weight of the diamonds alone is 25,300 carats; pearls 6,300, sapphires 4,300, emeralds 3,200 and uncut rubies 1,300, and also a great variety of miscellaneous stones." Oh, and by the way: "The collection does not represent all the Russian crown jewels, only those covering the last 200 years. The jewels worn by Russian potentates prior to the Seventeenth Century are still in the Kremlin at Moscow or the Hermitage Gallery at Leningrad." The story even included estimates of how much each ruler had contributed: 20% by Peter the Great 20%; 40% by Elizabeth, Catherine II and Paul I; 25% by Alexander I and Nicholas I; 10% by Alexander II and Alexander III; and 5% by Nicholas II. "So, contrary to general belief, the last Czar and Czarina were relatively moderate in their expenditures for crown jewels. During the last years of her life the Empress was so absorbed in mysticism that she regarded the wearing of jewels as unlucky and cast them aside."

AP on February 5, 1926 upped the number of crown jewels to "496 separate objects, [which] have been recorded in four elaborate volumes published today by the jewel department of the Soviet Government" and issued in Russian, English, French and German under the editorship of S. M. Troynitsky [sic] and Russian mineralogist Prof. A. E. Fersman. "Government authorities say the purpose of these books is, first, to repudiate the rumors abroad that the crown jewels have been sold or broken up; second, to make a contribution to the Science and History of Mineralogy; third, to leave for future generations of Russians an accurate and authentic description of the gems which the Government expects soon to convert into cash; fourth, to acquaint intending foreign purchasers with the details of the collection, which is described as the greatest aggregation of regal jewels in all history." And AP dropped this little bombshell: "Today, for the first time, it was disclosed that the Bolsheviki lost all trace of crown jewels valued at $264,000,000 for four years after the Bolshevist revolution of 1917. For a time it was feared that Kerensky, head of the Government overthrown by Lenin and Trotsky, had sent them secretly out of Russia. After an incessant search, however, they were found late in 1921 in the armory of the Kremlin, stored in wooden cases in an obscure corner. They had been sent hurriedly from Leningrad to Moscow late in 1917 when the German forces occupied Riga and were threatening Leningrad." This, then, led to rumors that the jewels had been sold or dispersed. The same February 5 article stated that gem experts from seven countries were vying for the jewels. "Americans are the most active bidders, closely followed by French and British experts." The story stated that "Rudolph Oblatt, representing a syndicate of American diamond firms, today made a bid for the entire collection of unmounted emeralds, which is valued at several million dollars and comprises stones up to 65 carats in weight."

Emperor Nicholas II crowning Alexandra Feodorovna in the Uspensky Cathedral in 1896.

Finally, a Sale, and Another

A New York Times story datelined February 10, 1926 read:

A large consignment of the imperial Russian jewels was recently disposed of in London. Much secrecy is preserved in Hatton Garden, the centre of London's jewel trade, but it is admitted that one man who rents a tiny office made $200,000 in commissions as the agent in selling some of the jewelry.

One emerald included in the consignment is said to have been valued at $1,250,000, while $500,000 was asked for a rope of pearls. One diamond ring was sold which was described as Alexander I's diamond wedding ring.

On February 12, the New York Times reported that $5 million worth of the jewels already had reached London. A roadblock was set up, however, by the Russian Lawyers' Association in New York. "It will be alleged that the jewels are stolen property, that the Soviet Government never acquired lawful title to them and that they legally belong to the heirs of the House of Romanoff, to other Russians of every class and, in some cases, to churches, public, social, benevolent and other institutions of the old régime." Individual jewels described in the lot were an emerald once belonging to Ivan the Terrible worth $1.25 million and a pearl necklace valued at $2.5 million.

The Russian Lawyers' group needn't have worried, at least for the time being, since American efforts to purchase the jewels failed. A Times story datelined February 22 noted, "Twoscore jewelers flocked to Moscow from New York, London, Antwerp and Paris" for an entire parcel of the crown jewels. Given that the Soviet government had decided not to divide the parcel, ultimately only two groups vied for the prize, "the French jewelers' group represented by M. Frankiano and the American-British group, consisting of Rudolph Oblatt and Adolph Pressels of New York and Norman Weiss and Solomon Himmelblau of London." The French finessed the deal, outbidding the American-British group by $130,000 (£540,000 over £525,000) before the Americans had time to counter-offer. "An American lawyer appealed to the Kremlin on behalf of the American-British group maintaining that opening the bids without all the bidders being present was manifestly unfair." The government agreed, annulling the sale, but insisted on sealed bids; the ranking, however, remained the same, £603,000 to £575,000. "The parcel consists of diadems and the last Czarina's crown, also 30,000 carats in loose diamonds, many emeralds and sapphires. They were sold at their intrinsic value, not at the antiquarian or historic value," the Times wrote. The article closed with: "One of the largest Amsterdam diamond brokers, who saw the whole collection two years ago, afterward declared in London he would not guarantee to dispose of a third of it in less than five years without breaking prices throughout the world."

The Last Empress. Alexandra Feodorovna, 1908. (Photo: Boasson and Eggler)

Only a Rubellite

Later in 1926, one of the most famous of the Russian crown jewels, a 250-carat ruby once owned by the Swedish Crown, was downgraded by none other than Prof. A. Fersman, who had co-edited the four-volume catalogue earlier in the year. Writing in the Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Science, Fersman wrote, as quoted by AP on November 13, "It was, as a matter of fact, a light red tourmaline from Burma (rubellite)—Genuine [sic] rubies are always dark red—weighing 250 carats, of irregular shape and representing nothing exceptional either as to size or quality." The stone had been given to Catherine the Great in 1777 by Swedish King Gustavus III, who had removed it from his own crown collection illegally. Interest in having the stone repatriated "has cooled," AP wrote.

Jewels Sold, Challenged

The next day, November 14, AP reported that the American-British group, which in February had failed in its attempt to buy a parcel of the Russian crown jewels, had succeeded in purchasing the following: Catherine the Great's "nuptial crown," containing 1,520 diamonds, worn when she married Peter III in 1745, and valued at $52 million; a baby rattle of gold and ivory used by the last Czar, valued at $5,000; a diamond-studded three-edged sword studded with "1,000 diamonds of the first water and ancient cutting" that belonged to Paul I, "it being [his] practice to single out whole regiments with this sword for Siberian exile if they failed to gratify his caprices"; a hat of pure gold studded with diamonds, rubies and emeralds created for Paul's pet monkey; a gold snuffbox containing two thousand diamonds used by Peter the Great's daughter Elizabeth, valued at $15,000; and a bodice ornament worn by Catherine II at her 1762 coronation, "consisting of huge clusters of many-hued Brazilian diamonds, Indian emeralds and other stones."

And the Russian Lawyers' Association? The buyers weren't worried. "There is no legal obstacle to the sale of the Russian crown jewels in the United States, Rudolph Oblatt […] declared yesterday," as reported by AP on November 15. "The Russian Lawyers' Association could not interfere, [Oblatt] said, as he had ample authority for all the transactions involved." One troubling detail: the jewels could be sold as-is in their settings, Oblatt said, but they could be dismantled. "This was done in a recent sale of some of the crown jewels amounting to $3,000,000, to save the 12 per cent French duty on mounted gems. Expert setters were brought to Moscow from Paris and the pieces were all destroyed. The gold was melted and the unmounted jewels taken to France." In case Oblatt received legal objections that carried weight, he reminded AP that his partner Norman C. Weiss was a British subject; Oblatt could purchase the jewels from Weiss rather than from the Soviet government. For its part, the Russian Lawyers' Association was not amused. Its Secretary J. J. Lisstzyn issued a statement saying the group stood ready to render support to the legal owners of the jewels. It was keeping its legal options open.

Part 3

We left off in Part 2 with an American and British consortium of dealers having successfully purchased a parcel of Russian crown jewels in mid November 1926, to the distress of the Russian Lawyers' Association. If the Association went to bat for the "rightful" owners of Russian jewels, it was not reported by the New York Times. Just before the end of the year, articles in the press discussed the Soviet government's money troubles.

Brother, can you spare a loan?

An AP story datelined December 29, 1926 stated that, following the American-British sale the month before, the Soviet government "yesterday sent several million dollars' worth of royal and other gems to Berlin for disposal there." The key phrase, of course, is "and other gems," since as we've seen so far, much of what the Russians unloaded was gemstones amassed from private hands by the Soviet government after the 1917 revolution. The consignment was to be handled by Gregory Swanson, the Soviet financial agent in Berlin. Swanson had been "instructed to accept payment either in cash, machinery or goods," AP reported.

On January 2, 1927, the New York Times, with its own Moscow correspondent, looked at Russia's options, as Leon Trotsky appeared to be in decline and Joseph Stalin ascendant. In a routine that would become familiar up to the present, the Times wrote in its op-ed piece that day that Russia required funds to stimulate its "languishing" industries. The Trotsky bloc urged taxing "the peasantry"; the Stalin faction want foreign cash. "Capital is not prejudiced in favor of any political régime," wrote the Times, "but demands stability and security." Just what exactly Capital considered to be stable and secure would become apparent during the rest of the 20th century. "It will not trust itself in Russia so long as the conflict of parties and expediencies is reflected in a cat-and-mouse policy toward private enterprise." That cat-and-mouse policy also would manifest itself until the Soviet Union's unraveling began in 1989. The sale of Russian jewels—royal or not—was due to a failure of the Soviets to obtain foreign loans. Even a $75 million line of commercial credit sponsored by Germany in the summer of 1926 had only been partially tapped, for reasons unknown; no loans had been secured from the United States. Stalin's faction "continues to invite foreign capital while reasserting its mission to overthrow the 'capitalist world'." The Times concluded that, when Stalin, "or any one who may take his place, feels himself strong enough to inform the faithful that the Communist midsummer night's dream is over, that the outside capitalist world is there to stay, and that Russia badly needs capitalist money, there will be a chance of funds for Russian industry from other sources than the sale of the Romanoff jewels."

Ten days later, on January 12, AP once again pointed out that nearly $1 billion in precious stones "piled up by the Czars of Russia in a thousand years of the nation's life, remain in the steel vaults of the Kremlin, and the Soviet authorities say they will not be sold except as a last extremity." The Berlin sale, AP stated, would "embrace only those worn by Emperors and Empresses during the last 200 years." Whew! The jewels had been sent to Berlin because Americans were no longer in the market for them, having maxed out at the purchase already of gems worth $300,000. "The [Soviet] Government still has nearly 400 separate pieces."

Carl Fabergé (1846–1920), Fabergé workshop, Mikhail Perkhin (workmaster). Imperial Peter the Great Easter Egg, 1903. Egg: gold, platinum, silver gilt, diamonds, rubies, enamel, watercolor, ivory, rock crystal. Surprise: gilt bronze, sapphire. Egg: 12 x 7.9 cm, Surprise: 4.7 x 6.9 cm, Stand: 7.7 x 6.9 cm, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest of Lillian Thomas Pratt. This was featured in Faberge, Jeweller to the Czars last year at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. (Photo courtesy The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts)

The same Easter egg, with its "surprise" exposed.

Christie's Catalogue

A New York Times article datelined February 21, 1927 announced a sale on March 16 by Christie's of some of the jewels heretofore described. A nuptial crown, "which is entirely composed of a double row of fine brilliants in borders of small stones and surmounted by a cross of six large brilliants"; "a diamond tiara designed as wheat ears and foliage and set with briolet and oval brilliants, the largest centre stone being a white sapphire"; and "a court sword of which the hilt and guard are entirely composed of brilliants, […] said to have belonged to Paul I." The jewels were being offered via Christies by a British syndicate that had purchased them, but wished to close out a partnership account.

A New York Times follow-up on the Christie's sale noted that although it brought in $400,000, it was not a record for the auction house, and the "jewels disposed of were not the most famous handled there, nor were they the cream of the Russian imperial collection."

Brother, can you spare a tractor?

As I mentioned at the outset of this look at the Romanoff jewels, an AP article datelined July 24, 1929 was what originally caught my eye regarding the attempt of the Soviets to sell. An alternate version of that story appeared in the New York Times, stating that an unofficial American delegation had been touring Russia, buying up artworks and being offered jewels. They "viewed today a part of the $264,000,000 collection of crown jewels. They were told that the Soviet Government would like to convert these gems into ploughshares, locomotives and tractors. Some of the Americans expressed a wish to buy some of the jewels, but they withdrew their offers when told that the least expensive item in the collection was priced at $1,000,000."

Carl Fabergé (1846–1920), Fabergé workshop, Saint Petersburg, Carl Faberge (work master). Scarab Brooch, about 1900. Garnet, gold, diamonds, rubies, enamel, silver. 2.8 x 3.8 x 1.9 cm. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest of Lillian Thomas Pratt. Also featured in Faberge, Jeweller to the Czars last year at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. (Photo courtesy The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts)

The next mention of Russian imperial jewels, in my admittedly unscientific survey of 20th-century newspapers, is of a robbery on May 10, 1935 of Imperial Art Treasures on New York's Fiftieth Street. A man about thirty years old visited the gallery a few days before, asking for a catalogue. Apparently having made his selections, the man returned and drew a pistol, tying up the manager and helping himself to, amongst other things: "eight gold snuffboxes in the form of crowns, a pair of gold cuff links marked with the imperial crown and a gold brooch mounted with the imperial Russian eagle in sapphires and diamonds." The loot was valued at $10,000.

More loot was taken in early 1939, this time legally via transfer to Poland from the Soviet Union according to a 1921 debt agreement. Per that agreement with Poland, Russia was bound to pay the Poles roughly 30 million gold rubles for treasure taken from their country. Being cash-poor, Russia deposited imperial jewels worth about half that amount for fifteen years. The jewels were forfeited by default when the debt was not paid. They were to become the property of Poland on January 1, 1939 as reported by the New York Times a week later.

The Luck of the Irish

At least by 1948, revelation of the pawning of another parcel of what may have been Romanoff jewels came to the public's attention, via an August 4 article in the Irish Times. "What is to be the ultimate fate of the Russian jewels given to the Irish Government in 1920 as security for a loan of about $20,000 to the Russians and never redeemed?" the article asked. Without reporting on how the loan came to be, the jewels were described. "The set comprises four pieces of diamonds with topaz, mounted on platinum, with safety locks. One piece is a big cluster, which may have been part of a crown; the others are earrings and a pendant." The article discusses how the jewels might be appraised and then sold, whether an existing ban on export of gems and antiques might apply were the jewels to be sent to London for auction, whether Russia might buy them back, whether an heir might claim them, etc.

In an AP story datelined April 1, 1950, it was reported that "Russia has repaid $20,000 it borrowed from Ireland 30 years ago and has received in return the collateral—jewels which may once have belonged to the czar." A history of the transaction followed, but its description of the jewels themselves differed from the 1948 report.

A soviet delegation in the United States seeking American recognition ran short of cash. An Irish group also was in the United States trying to get American recognition of Ireland as an independent republic.

The Russians approached the Irish and got the loan in return for the jewels, which included pieces set with sapphires, rubies, and diamonds. Harry Boland, a member of the Irish mission, brought them back to Ireland.

He was killed in the Irish rebellion and his mother turned the jewels over to the Irish treasury. Gossip around here was that the gems came from the murdered czar's crown collection. Russia never said where they came from.

The loan's terms called for repayment upon demand, a demand that presumably had been made about the time of the 1948 article. The payment was made "on the barrelhead—in dollars," the AP story said, which was fortunate for the Irish government, whose information bureau concluded, "The jewels had been valued here by people in the business, who advised that the government would be lucky if they got up to 2,000 pounds [$5,600 at the present devalued rate] for them."

Carl Fabergé (1846–1920), Fabergé workshop, Mikhail Perkhin (workmaster). Miniature Easter Egg Pendant, about 1900. Chalcedony, gold, white gold, diamonds. 3.2 x 2.2 cm. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest of Lillian Thomas Pratt. Also featured in Faberge, Jeweller to the Czars last year at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. (Photo courtesy The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts)

Museum Quality

The New York Times and other dailies were mute on the subject of the Romanoff jewels for years. In a Times story datelined November 9, 1967, it was a announced the crown jewels had gone on display that day in the Kremlin. The exhibition included the Orloff diamond, Catherine the Great's coronation crown, and the Shah diamond. "Some of the diamond treasures now on permanent display were last shown in 1924," the Times wrote, "when the Soviet Government invited foreign diplomats to inspect them to dispel rumors of pilferage, sale abroad or loss during the revolutionary upheaval of 1917." (Not mentioned was the fact that the jewels indeed had gone missing until 1921, as noted above.) Along one wall, the Soviet diamond industry was mapped via large color transparencies, and photographs showed work at a major diamond-cutting plant in Smolensk, employing 2,400 workers. "'Fifteen years ago,' an official of the diamond display said today, 'no one in the West would sell us diamonds for industry. We were forced to go find our own diamonds. We did, and now we are among the world's leaders in diamonds'." This recalls the fact that post-revolution Russia had influenced the diamond market decades before, by virtue of the sheer numbers of the stones that were offered by Russians wanting to divest themselves.

Twelve years later, the imperial jewels traveled stateside, as reported by the New York Times on May 13, 1979. "Now for the first time an exhibition of 100 of the Kremlin museums' most precious objects—the 'Crown jewels'—has come to the West and will open Saturday at the Metropolitan Museum of Art." The exhibition, titled "Treasures from the Kremlin," "chronicles Moscow's spectacular rise from an obscure backwater town to the political and cultural center of a modern nation."

Carl Fabergé (1846–1920), Fabergé firm, St. Petersburg, Henrik Wigstrom (workmaster), Vasili Zuev (miniaturist). Column Portrait Frame with a Miniature of Nicholas II, Imperial presentation gift, 1908. Gold, silver, diamonds, ivory, watercolor. 15.2 x 5.5 x 5.5 cm; miniature: 3.1 x 2.5 cm. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest of Lillian Thomas. Also featured in Faberge, Jeweller to the Czars last year at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. (Photos courtesy The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts)

In late January of 1997, "Jewels of the Romanovs: Treasures of the Russian Imperial Court" graced the rooms of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. This time, however, there was a bit of a snag, causing Russian and American curators to work non-stop to install the exhibition. The minor objects (relatively speaking), "including royal portraits, letters and photographs; examples of court gowns and military dress and numerous ecclesiastical objects in gold, gems and mother-of-pearl, had arrived more or less on schedule," the New York Times wrote on January 29. "But the imperial jewels from the Russian State Diamond Fund that formed the heart of the show were a different matter. After all, they include a 19th-century brooch incorporating the world's largest sapphire, a bracelet in which the world's largest table-cut diamond in the world serves as a pane of glass, and a blue diamond stickpin whose stone is rumored to have come from the Hope Diamond, just a few blocks away at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History." According to the article, since the Kremlin began public viewing of the jewels in 1967, the Diamond Fund had only allowed five or ten jewesl at a time to be lent from the Kremlin. (This calls into question just how precious the "100 of the Kremlin museums' most precious objects—the 'Crown jewels'") of the 1979 MoMA exhibition actually were.) The present exhibition was to include 115 pieces.

What ensued was comical. "At first the fund curators were reluctant to transfer the jewels from the Russian Embassy to the museum, which meant that when they finally arrived on Friday, Corcoran staff members had to rush to make the brass mounts to hold them upright in their cases. The installation was further delayed when the Russians decided that the cases themselves needed thicker glass. Anyone who saw the state of the galleries late Monday would not have believed that the show would be ready for today's press preview." James Symington, chair of a show sponsor, the American-Russian Cultural Cooperation Foundation, called the whirlwind mounting of the exhibition, "a miracle on 17th Street," in reference to the Corcoran's location. The crown jewels were stars of the show, of course, but "the Russian curators who selected the exhibits wanted to highlight jewelry making in Russia today," and this was a flop. "Thus near the show's finish is an anomalous vitrine containing several contemporary brooches, earrings and necklaces, none of which have the visual presence or historic credentials of the earlier pieces." If only they'd been able to include "three exceptionally complex pieces produced by Diamond Fund jewelers in the 1980's and 90's and based on jewels sold during the Communist era [that were] nearly as dazzling as anything here, especially a sparkling diamond tiara from which an intricately cut yellow diamond shines forth like a not-so-little headlight." And this, if you'll recall, is just the sort of metaphor used by the workman in 1922 who showed to New York newspaper correspondents the Empress Elizabeth's neck ornament with rubies "big as the signal lamps of a liner."

Notes

1. The Post-Dispatch stated that the "soviet authorities are issuing this week three elaborate albums containing photographs of the Russia crown jewels," but the catalogue in the personal library of George F. Kunz, now housed at the National Geological Survey Library, consists of a single volume.

2. See Richard W. Hughes, Ruby & Sapphire (Boulder: RWH Publishing, 1997), pp. 234, 247, 282, for identification of the stone as a spinel weighing either 414.30 ct or 398.72 ct.

3. Prince Michael of Greece, Jewels of the Tsars: The Romanovs & Imperial Russia (New York: Vendome Press), p. 14, states that Catherine II commissioned Swiss jeweler Jérémie Pauzié to create the crown, for which he selected the imperial treasury's largest stones.

4. Duranty begins his story, carried in the 16 Jul 1924 edition of the New York Times, "A year ago my eyes were dazzled by the splendor of the Romanoff crown jewels at the headquarters of the Moscow Jewel Commission." I am unable to find any reportage in the Times by Duranty that he had a repeat viewing of the jewels the summer of 1923. I believe this is an error not caught by his editors.

5. See Note 3 above.