Buried Treasure

Buried Treasure

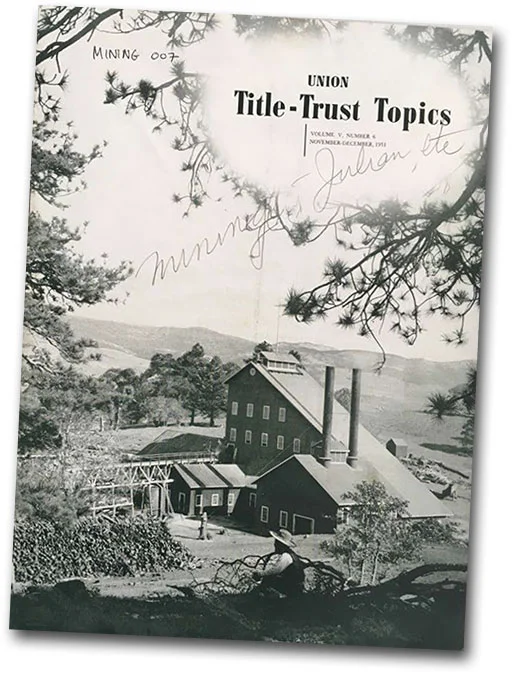

The Story of San Diego County's Mining Industry

The following article appeared in Union Title-Trust Topics, Vol. V, No. 6, November–December 1951.

Even twenty years after Jim Marshall's discovery of gold on Sutter's Creek, Californians weren't cured of their Forty-Niner-brand of gold fever…they were only convalescing and, with the night follows day sort of inevitability, talk of a new Gold discovery brought back the fever in full force.

San Diegans weren't immune and the gold bug swept in their town, in all but epidemic proportions, early in 1870.

It all started when rumors of a gold discovery began to filter in to San Diego. "Mike and Webb Julian found placer gold north of Cuyamaca," went the tale…and the story grew.

In fact, so rapid was the growth of the Gold story that the "San Diego Weekly Union," on February 10, 1870, thought to quiet the rumor with a brief matter-of-fact announcement, "We do not wish to see any rush of excited miners to San Diego on account of the rumors, nor even in view of the facts which have as yet been developed. We shall rejoice in the discovery of mineral wealth within our borders; however, we believe the growth of San Diego as a city will not be gratefully promoted by mining enterprises. Our true source of strength has been in our natural advantage as a commercial port."

The Union's plea for a safe and sane approach to talk of gold must have fallen on deaf ears, for a week later the paper rather grudgingly admitted that there were "75 prospectors on the ground" in the back country "gold strike" area.

The February 24th issue of the Union leveled off at the opposition paper, "The San Diego Bulletin," with the charge that the Bulletin's editors were reporting gold discovery rumors as fact and were helping create an unjustified gold rush into the mountains of San Diego County.

"This week, 1500 pounds of rich, gold-bearing quartz…came in from Cuyamaca," was the story in the Union on March 10th, and the rush was on!

The rich haul, examined and described by the Union's editor, came from the George Washington Mine, discovered on February 22nd by H. C. Bickers, who had been prospecting six miles north of Cuyamaca with J. B. Wells and J. T. Gower. Theirs was the first of the truly rich gold strikes in the country and their 1500-pound shipment of rich quartz kindled the gold fever in all but the most moribund San Diegans. In fact, even the heretofore anti-gold-rush leanings of the Union's editor evaporated and the paper began an enthusiastic series about the gold discovery, reporting in the March 10th issue that the population of "Julian City," the principal mining camp, was "600 persons and the number is daily increasing…"

By the middle of March, the Union had a correspondent at the mines, who wrote, "Probably 800 people are in camp in the Julian District and about 150 at 'Colmera City' (3 miles west of Julian)." The correspondent, who woefully complained of his own ill fortune in locating a valuable "ledge of gold," wrote, "…I believe that I am warranted in saying that no richer quartz district than this has been opened in California…"

The end of March saw the population of Julian City totaling "perhaps 1500," according to both the Union and the Bulletin, then in complete accord about San Diego County gold discoveries. It was the Union of March 31st that told of the discovery of what proved to be one of the richest mines in the area, the Stonewall Jackson, reported to have produced some $5,000,000 worth of gold. This mine, said the Union, was discovered some ten miles from Julian City by Charles Hensley, who located "…a well defined ledge two feet wide. The ore there is of great richness, every piece being studded with gold." The report continued, "…ten hours after Hensley's discovery, there were 500 people on the ground…"

And so it went. Discovery piled upon discovery and more and more miners swarmed into the mountains to seek their own mines to work in one of the 30 producing mines in the area.

Nothing was missing in the gold region…the picture was complete. Julian and its sister mining towns boasted of swarms of tents, hardware stores, saloons, and Julian even had a "Vigilance Committee." In reporting on the activities of this committee, the Union's hard-working mine correspondent wrote, "…several horses were missing and Crawford was suspected of working with a gang of horse thieves. The Committee took him out and hauled him up to the limb of a tree once or twice when he confessed to stealing a saddle and that he was 'in' with two or three other horse thieves." Crawford, thus intimidated, was run out of town and warned never to return to Julian. The vigilantes had one more job to do that day, according to the reporter, who wrote, "The Committee passed a resolution to hang the first man to commit a murder here."

New mines continued to be developed during the two decades that followed the initial discovery of workable quantities of gold in San Diego County. Between 1870 and 1880, over $10,000,000 worth of gold is said to have been taken from mines in the Julian-Banner-Cuyamaca region. Best known mines of San Diego's gold rush era included, in addition to the famed George Washington and Stonewall Jackson mines, the Golden Chariot, Redman, Kentuck S., Ready Relief, Ranchita, Elevada, Blue Hill, High Peak, Helvetia, Pride of Julian, Ella, Gypsy, Cincinnati Belle, Valentine, Mary Emma, Pride of the West, Hubbard, Antelope, and Shamrock.

Profitable operation of San Diego County's gold mines continued until about the turn of the century, when the king-size batch of troubles descended upon the miners. First, and perhaps most important, was the general decline in the value of gold ore taken from the mines. This fact, however, might not have spelled the end of major gold mine operations in the region, because volume production of even lower grade ore would have enabled most miners to continue operation and show a profit. But adding to the declining values of gold was the serious problem of greatly increased mining costs. Chief among these problems with the never-ending battle to prevent underground springs from flooding the mines. Pumping plants were built, pipe lines laid deep underground, and water was pumped from the mines. Then, as the mines went deeper, greater quantities of water were encountered and two more pumps were required to stem the flood. The "more water, more pumps" cycle continued until the early 1900's, when mine after mine began to shut down.

Flooding wasn't the only factor that caused once profitable mines to be abandoned. In addition to flooded workings, mine operators had to contend with increasing costs for milling their ore and extracting the gold it contained. Then, too, the Gold Reserve Act of 1900 pegged the price of gold at $20.67 per fine ounce—a matter of a dollar or so less than the miners could get for their gold on the previously "open" market.

Rise of Other Mining Activity

However, the decline of San Diego's gold mining industry in the early 1900's didn't mean that San Diegans would never again enjoy the frenzy of another Bonanza-like mineral discovery.

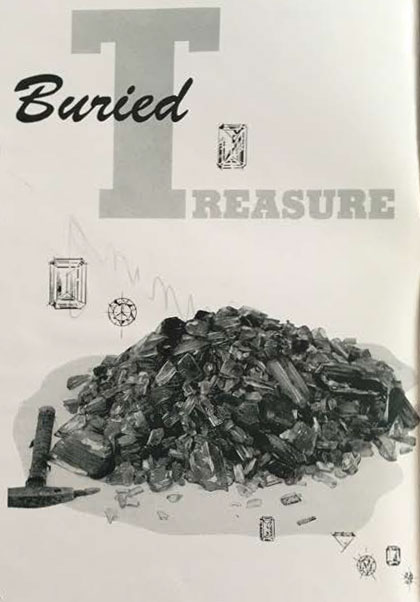

The frenzy did hit again—this time in the early 1900's—following discovery of the gem stones in the northern part of the county. The gems, while not including diamonds, rubies, and other extremely precious stones, did comprise a number of somewhat less valuable gems—a glittering array that included tourmaline in its wide, rainbow-like the assortment of shades, plus the equally beautiful kunzite, beryl, and topaz.

The article title is accompanied by the photograph of a pile of kunzite, valued at more than $15,000, which George Ashley discovered in the mine shown below.

In one of his mines near Pala, George Ashley, right, points out mineral specimens to Roy M. Kepner, Jr., of the County Division of Natural Resources.

Beginning of the Gem Industry

The story of tourmaline and other precious stones in San Diego County's gem-producing areas goes back thousands upon thousands of years when, from the core of the earth, streams of molten rock were forced up through cracks and fissures in the granite mountains of this region. Cooling, this lava "froze" in pockets, layers and seams, and in the cooling and "freezing" process, minerals crystallized to form the gem stones found today in San Diego County gem mines. The gem-bearing deposits, generally known as "pegmatites," are found at several places along the broad band which sweeps from the northern boundary of San Diego County, through the Pala region, on through Ramona and Julian, and to the southernmost part of the county near Jacumba.

The pegmatites, usually identified by their light color, generally are found in the roughly parallel bands or "dikes" which run along the sides of mountains and which, occasionally, may be seen where a highway follows a cut through a hillside. However, not all pegmatites have gem-bearing pockets. To be a source of gem stones, pegmatites must have contained certain essential elements during their volcanic formation.

Another clue to the location of gem deposits in the pegmatites is the occurrence of lepidolite, a lithia-mica mineral that is a source of the lithium and is supposed to be the agent that gives tourmaline its most common pinkish hue. Soda feldspar is another mineral that is an important clue to the location of San Diego County gem stones, for in most cases tourmaline and some of the county's other precious stones are found in so-called "gem clay," a spongy mass of decomposed feldspar.

First Gem Discovery

The first hint that Southern California ultimately might become one of the world's gem-producing centers came during the heights of San Diego County's gold rush and was all but overlooked in the furor surrounding the rapid sequence of gold strikes in the Julian area. It was in 1872 that Henry Hamilton, prospecting in what is now Riverside County, made the first discovery of gem-tourmaline in California.

Presumably, tourmaline was discovered in San Diego County's Pala region, west of Palomar Mountain, the following year, but, according to a publication of the California Bureau of Mines in 1905, miners weren't particularly anxious to reveal their finds. This publication reported, "…the parties who knew of the occurrence (of the gems) did not make it public for some years, and the earlier specimens were taken out quietly and their locality not divulged…"

It wasn't until nearly 20 years later that real publicity was given the gem deposits in the county. This, in 1892, followed Charles R. Orcutt's discovery of tourmaline near Pala.

Orcutt, and quite possibly Hamilton, were searching for lepidolite, for the lithium-bearing mineral was then in demand by the glass manufacturing industry. Both Orcutt and Hamilton found their tourmaline crystals surrounded by flaky, lilac-colored lepidolite.

While both early discoveries of tourmaline revealed only the deep pink crystals of the gem, tourmaline soon was found in a wide range of colors, including red, salmon, green, dark blue, and black. Also discovered was a multi-colored tourmaline which has bands of different colors appearing within the length of a single crystal. Tourmaline crystals generally are shaped like short lead pencils, with a diameter from about an eighth of an inch to as much as four or five inches.

News of the early discoveries of tourmaline and other gem stones didn't particularly excite San Diegans—they were more impressed by the potential value of the county's lepidolite-lithium deposits, for lithium was bringing a good price. It was natural, then, that while literally hundreds of prospectors were searching for lithium-bearing minerals, they discovered a number of worthwhile deposits of tourmaline. It was these lithium-tourmaline mines that gave the county's gem mining industry its first real boost.

By 1905, scores of mines, large and small, were being developed or worked in the Pala, Julian, Mesa Grande, and Jacumba regions. Perhaps the most spectacular of the group was the famous Himalaya Mine, some 11 miles south of Palomar Mountain, which has been labeled "…the greatest producer of gem tourmaline in North America" by Dr. Richard H. Jahns, Caltech scientist and one of the world's leading authorities on pegmatite formations.

The Himalaya, whose output has been estimated to have been worth well over a million dollars, was the site of the pegmatite formation well laden with beautiful pink tourmaline. Strangely enough, this mine owed much of its prosperity to the demand for the pink gem in China, where it was much favored by the reigning empress. Literally tons of the San Diego County gem were shipped to China, there to be carved into figurines and ornaments. Another unusual aspect of the Chinese demand for the pink tourmaline was the fact that the rather opaque stone was more highly prized in the Orient then the brilliant crystals so much in demand throughout the world today.

During their search for the opaque pieces of tourmaline for the Chinese market, the Himalaya's miners discarded clear, colorful crystals of tourmaline. In later years, the Himalaya's dump became a veritable treasure trove, so heavily was it laden with once discarded gem tourmaline.

Left, members of the Convair Rockhounds Club are shown cutting and polishing San Diego County gem stones in their clubroom lapidary shop. Center left, the entrance to the Vanderberg Mine, scene of George Ashley's $15,000 kunzite discovery. Center right, skilled worker prepares to split black granite boulder taken from quarry near Escondido. After rough splitting, granite goes to the slabbing machine (at right) which actually saw the stone into slabs prior to final polishing. Right, onyx, mined in Baja California, is brought to San Diego to be cut and polished into desk pen bases.

A New Gem

While tourmaline had been discovered and mined commercially in other parts of the world, notably Brazil and in parts of New England, San Diego County gem prospectors did establish a "first" with the discovery of a gem peculiar to this region.

The discovery occurred when M. M. Sickler and his son Frederick were working on a lepidolite deposit northeast of Pala. As Dr. Jahns described the discovery in Engineering and Science Monthly, "the Sicklers encountered numerous transparent masses of the mineral colored in delicate tints of pink, lavendar, lilac, and blue-green. These were subsequently identified as a rare, remarkable clear variety of the lithium-bearing mineral spodumene. The pinkish to lilac-colored types were given the name 'kunzite' in honor of Dr. G. F. Kunz, who first identified the gems in his capacity as mineralogist for Tiffany and Company of New York. Kunzite thus is one of California's own minerals."

It wasn't long after the Sicklers' discovery that additional spodumene and kunzite deposits were located in the Pala area by such pioneer gem miners as the late Frank Salmons, Bernardo Hiriart, and Pedro Feiletch. Then, in short order, came the discovery of transparent quartz crystals and of an unusual peach-colored beryl. This local beryl, a truly beautiful gem stone, was named "morganite," honoring J. P. Morgan.

By 1905, the mines in San Diego County's pegmatite formations were producing a wide variety of minerals and gem stones. Chief among the commercial minerals taken from these mines were the various ones yielding lithium compounds, which were used in glass and ceramic industries. (Lithium, for example, is used in glass to increase luster, electrical resistance, and strength. Glassware containing this element is currently used in high pressure gauges, electronic tubes, and in similar products that are subjected to shock or sudden temperature changes.)

Lepidolite was mined for its lithium content for many years, with peak production occurring just before 1920. In that year the local lithium mining activity was all that halted because of the development of larger and better lithium deposits in New Mexico. With a decline in the production of the lithium-bearing ore, gem mining, too, slumped in San Diego County. The decline of the gem mining industry at that time doubtless was helped along by the over-production of gems, particularly tourmaline, during the 1905–1920 period.

So it was that the gem mining industry, except for the limited production of a few scattered mines, was dormant by the middle 1920's, not to be re-awakened for a decade.

Then the "Rock Hounds"

Searching for unusual mineral specimens has been a popular hobby for many years, but the activity did not become of major importance until the early 1930's, when thousands found it an entertaining—and often profitable—pastime.

The steady growth of this interesting hobby has brought about the formation of a number of mineral societies in San Diego County. Included are the San Diego Mineral and Gem Society, the Convair Rock Hounds, the San Diego Lapidary Society, the Tourmaline and Gem Mineral Society, and the de Anza Society.

As "rock hounds" the nation over began to collect unusual mineral specimens and, in many instances, to cut and polish their more beautiful gems and other mineral specimens, the demand for the unusual San Diego minerals began to grow.

By World War II, there was a nation-wide demand for such local gems as tourmaline in its wide range of colors, kunzite, spodumene, beryl, and clear quartz crystals.

To meet this demand, some of the country's original gem and lepidolite mines were reopened, old mine dumps screened time and time again in search of gems that might have been missed by earlier miners, and a stepped-up search for new mines begun.

This, of course, suggests a picture of the large-scale mining activity, with hundreds of men working with powerful machines to bore deep into the earth in search of valuable mineral material. This is not the case at all. Actually, gem mines in San Diego County are not particularly impressive. Little expensive equipment is required and in most cases the mine owners are their own "crews," working in their mines on weekends or holidays. As one Pala-region mine owner said, "It isn't a mine—it's just a damn profitable part-time gopher hole."

Recently, another mine owner, who was showing a party of geology students through his rather unimpressive diggings said, "Y'know, this old mine doesn't look like very much. But," he added quietly, pointing to a two-foot-square hole in a tunnel wall, "I got almost $8,000 worth of kunzite out of there a few months ago."

The booming hobby and the stepped-up activity in the gem mining business also has brought a re-birth of the ancient art of highgrading, a skilled and larcenous calling that had many nimblefingered practitioners during the gold rush days.

Highgrading, quite simply, is a rather energetic brand of thievery which calls for the highgrader to enter a mine (not his own) while the owner is away and then to spirit away any minerals of value.

Most of the gem mines of San Diego County are relatively easy pickings for highgraders, who risk their lives to prowl through unfamiliar mines in search of specimens they covet. However, while highgrading sounds simple, actually it requires hard work, plus a thorough knowledge of mineral formations. Although highgrading is a serious problem, it does have several amusing sidelights.

Take, for example, the told and retold story of the six or eight highgraders who stole into a mine at night. None of the gem thieves knew of the presence of the others and one slightly larcenous miner had the audacity to blast loose a promising section of the mine wall. Before the roar of the explosion had stilled, startled highgraders poured from the various entrances of the mine and went streaking into the night.

Gem Values Rise

Sparked largely by the demands of the nation's rock hunters and amateur lapidaries, prices for San Diego County gem stones have begun to rise. Many gems are sold "in matrix," the natural state, where the gem stones are still attached to the minerals that surrounded them in their pegmatites pockets. These "in matrix" items, of course, are eagerly sought by collectors, while the facet-cut gems from the local mines find ready markets with the nation's manufacturing jewelers. Current prices for facet-cut tourmaline range from about $5 to $25 per carat, kunzite demands prices of from $5 to $35 a carat, and the colorless to blue topaz from the Ramona and Aguanga regions gets from $5 to $15 a carat.

Obviously, with these prices currently being paid for facet-cut stones, the gem mining industry in San Diego seems destined for some degree of expansion in the years ahead.

A couple of mines are in regular production now and several others are scheduled to begin production in the near future. As these mines get into operation, the gem industry, from time to time, again buzzes with news of new discoveries. The single most exciting discovery of recent years was made in July, 1951, when George Ashley, long-time gem miner, discovered a "pocket" of kunzite in his Vandenburg mine near Pala. The mass of kunzite he discovered has been valued at more than $15,000. Interesting enough, Ashley's recent find was made not far from the site of kunzite's original discovery.

Still another discovery of a major kunzite deposit was made in May, 1949, when Charles Reynolds found about 300 pounds of high quality kunzite in the San Pedro mine, near Pala.

Other Mining Industries

For all their drama and interest, the gold and gem mining industries of San Diego County must take a back seat—at least dollar-wise—to a group of more prosaic but far more important mining activities—such as the one which mines and processes plain rock!

The "rock" industry, actually a three million dollar business last year, produces gravel and crushed rock for the building industry, and rubble and riprap for highways and for installations like jetties at the entrance to Mission Bay.

In 1950, according to a report issued by the Division of Natural Resources of the San Diego County Department of Agriculture, the total value of the output of the County's metallic and non-metallic mining industry amounted to $4,869,092.00. Of this sum, the gem mining production accounted for an estimated $52,000 and the combined output of gold, silver, and tungsten mines totaled about $3,500. The balance, a whopping $4,762,000, was the value of the County's output of sand, rock, granite, clay, and miscellaneous products such as filter pebbles, poultry grits, pyrophyllite, roofing granules, and terrazzo.

Left, J. C. Cloutman rolls an empty ore cart into the main tunnel of the Pawnee Mine, near Pala. This mine produced scheelite (source of tungsten) during World Wars I and II and now is being enlarged. Right, new milling equipment being installed at the Pawnee Mine will help boost tungsten production in San Diego County.

The County's "sand" industry showed up as a large one in the 1950 report with production valued at some $895,000. This industry produced concrete and plaster sand, and a specialized sands used in industrial molding, and in glass and ceramic manufacturing.

Clay products used in manufacturing fired brick and tile and adobe brick accounted for nearly $300,000 in 1950.

Of the miscellaneous products of San Diego County's mining industries, one of the most interesting is pyrophyllite, a grayish chalk-like material taken from a deposit between Rancho Santa Fe and Escondido and processed in a large plant in Chula Vista. The material, when finely ground, is used as a "carrier" for insecticide dusts and in particular for the type of insect-killing chemicals sprayed by crop dusting airplanes.

From open pit mines near Lake Hodges comes pyrophyllite, a chalk-like mineral that is ground to fine powder at this Chula Vista plant. The mineral becomes a "carrier" for chemicals spread by crop-dusting airplanes.

Silica sand, produced from sand-clay deposits east of Oceanside, is another interesting San Diego County mineral product, for this material finds widespread use as a filter element in large water-filter systems, as "blasting" sand for industrial use, and as high-quality sand for stucco and plaster.

From the feldspar deposits of the Campo-Jacumba region and from the limestone deposits in Dos Cabezas Canyon and on Coyote Mountain come both soluble and insoluble poultry grits used throughout Southern California. In addition, these mines, all located in the southeastern corner of the County, also supply feldspar and limestone roofing granules.

Plant of the Campo Milling Corporation, at Campo, where feldspar, limestone, and other minerals from the southeastern part of the County are refined.

San Diego County granite quarries and processors have received a boost from governmental restrictions on the use of bronze in monuments and as a decorative material. Their output, in ample supply, is finding greatly increased use in monument and construction work. Improved quarrying and processing methods have enabled the County quarries to compete on a more equal basis with midwestern producers. Chief product of San Diego County quarries is black granite which, when cut and polished, has a beautiful and distinctive luster. Granite from a quarry in the Ramona area is used in manufacturing insoluble poultry grit.

Another unusual product of San Diego County mines is montmorillonite, a non-swelling type of the earth that is used in oil filter systems. Largest deposits of this mineral are found near Otay.

What About Radioactive Minerals?

The world-wide search for radioactive minerals hasn't missed San Diego County. For several years, prospectors equipped with Geiger counters have swarmed all over the county, seeking minerals that might be sources of uranium. To date, no such deposits have been found, although a number of "uranium-less" radioactive ores have been located. Included among those ores which excite Geiger counters (and prospectors) are radioactive thorium, and such rare earth minerals as alleviate, cyrtolite, xenotime, and monazite. In addition, mildly radioactive specimens of iron have been located in San Diego County.

Needless to say, the search continues, and almost daily the County's Division of National Resources is called upon to examine possibly radioactive samples brought in by eager prospectors. These tests, as yet, haven't turned up any uranium, "But," cautions Roy M. Kepner, Jr., chief of the County's mining department, "let's keep looking!"

"Strategic materials," generally those in which the domestic supply is not enough to meet the demands of military and civilian users, are coming in for ever-increasing attention these days in San Diego County. Chief among these materials stirring up excitement at present is tungsten, which occurs in San Diego County in the form of scheelite. Mined here on a limited scale during both World War I and II, tungsten production is scheduled for a rapid upswing in the near future. Reopening of the Pawnee tungsten mine, between Warner's and Oak Grove, is the first step in increased local production of this strategic material. The Pawnee, an active producer during World War II, is being expanded and outfitted with new milling equipment.

The Palomar Scheelite Mine, located a few miles from the top of Palomar Mountain on the old grade, currently is producing a good grade of scheelite and shipping the tungsten-bearing ore to Lindsay, California, for processing.

Another of the strategic materials receiving more than passing attention is crystalline quartz, once used as a semi-precious gem and now in demand as a vital part of modern electronics equipment. Small amounts of this radio grade quartz are found in the pegmatites in the Pala region, from where, during World War II, several hundred pounds of the glass-like material were mined. San Diego County quartz, however, probably will continue to be largely a "by-product" of regular gem mining operations.

Mica, too, falls into the strategic materials classification, as it is vitally important in radio and other electronic equipment. Sizable local deposits of the flaky material had been found in the Jacuba region where mining and milling operations were carried on during World War II. Local mica production has been confined largely to processing this so-called "scrap" mica which, when ground, is used in rubber and paint manufacturing.

Although San Diego County boasts some sizable deposits of nickel, copper, and molybdenum, none are of such consequence as to warrant major developments at the present time. Larger deposits of higher grade ore are to be found throughout the United States and Canada, so local production of these metals doesn't seem probable in the immediate future.

San Diego county has the distinction of having within its boundaries workable deposits or recognizable traces of more different minerals than any other region of comparable size in the world, according to many mineralogists and geologists.

Who knows, then, when another major gold discovery will be made in San Diego County, or, perhaps, when copper, cobalt, lead, silver, asbestos, bismuth, or a host of other valuable minerals will be found here in bonanza-like quantities? There's no question about it. All these minerals—and many more—are to be found in San Diego County. Perhaps tomorrow a youngster will wander home carrying a chunk of heavy black rock that might set off the exciting, staccato chatter of a Geiger counter that means uranium! Perhaps next week a rancher will haul samples from a rich gold ledge to a San Diego assay office. And maybe before too long a rock hound, pawing through a mass of gem clay, might hit the jackpot of nature's treasure trove—diamonds…or emeralds…or rubies!

Exciting? Certainly. The mining industry is exciting, and as man has but scratched the surface in San Diego County in search of precious stones, valuable metal, and the more prosaic mineral products, there's no foretelling what remains to be discovered. It's anyone's guess.

The dynamic growth of the San Diego County area has placed heavy demands upon the rock, sand, and gravel industry. These important construction materials accounted for the largest part of the County's entire mineral output during 1950. The sand and gravel plants shown here, owned by the G. R. Daley Company, Is located in Mission Valley.