Eve and Her Jewel Casket

Eve and Her Jewel Casket

By Herbert P. Whitlock

The following is a reprint of an article published in the June 1938 edition of Natural History, the Magazine of the American Museum of Natural History (Vol. XLII, 7–11). The article later was published as a stand-alone volume; headings are taken from the original article. Herbert P. Whitlock was the museum's Curator of Minerals and Gems. See also Whitlock's "The Collection of Minerals in the American Museum of Natural History" on our sibling website, Palaminerals.com.

There always has been and there always will be an element of mystery in the appeal of the bits of bright and colored stones that we call gems. I am loth to believe that this appeal is solely to the sense of beauty although beauty has very much to do with it. Nor is it entirely a question of value although again the sentiment of value is very closely linked to the lure of gems. In many things, but especially in the buying and wearing of gems, we desire most that which is rare, that which other people cannot afford to have, that which proclaims our opulence. This is, of course, a more or less barbaric heritage, like boasting and shaking our fists in peoples' faces and generally making a spectacle of ourselves.

Real gems vs. synthetic

It is undoubtedly this element of our barbaric heritage that impels the man or woman of today to pay many times the value of a synthetic sapphire or ruby for a natural stone of the same kind. And this in spite of the fact that in all essential characteristics the two gems are identical, and no eye but that of a trained gemmologist can discern the difference between Nature's product and that which is made of the same substance by man.

But back: of all these considerations I am convinced that there lies a subconscious appeal, something psychic and primitive that moves us ofttimes to lie, murder and steal for the sake of some sparkling shred of mother earth.

And we have every reason to believe that this appeal swayed men and especially women before the beginning of history. The subtle charm that renders a modern woman spellbound before a jeweler's showcase is the same that urged her earliest forebears to hang bright colored stones about their persons before it occurred to them to adopt any other means of adornment. Jewelry is probably older than dressmaking.

Appeal of color

When we attempt to analyze the appeal of gem stones to our conscious rather than to our subconscious selves we find that much of our feelings toward them is linked with reactions to color. And color is by no means simple in its psychological responses. I once heard the story of a child that had been born blind, and who, upon reaching early manhood, was by some miracle of modern surgery, restored to the world of shape and color. So unusual was the situation involving someone who had lived hitherto in a darkened world and who was suddenly restored to sight, that people were interested in his first reactions to various colors. He was shown a piece of red stained glass, upon which he exclaimed directly, "That is like the sound of a blast upon a trumpet."

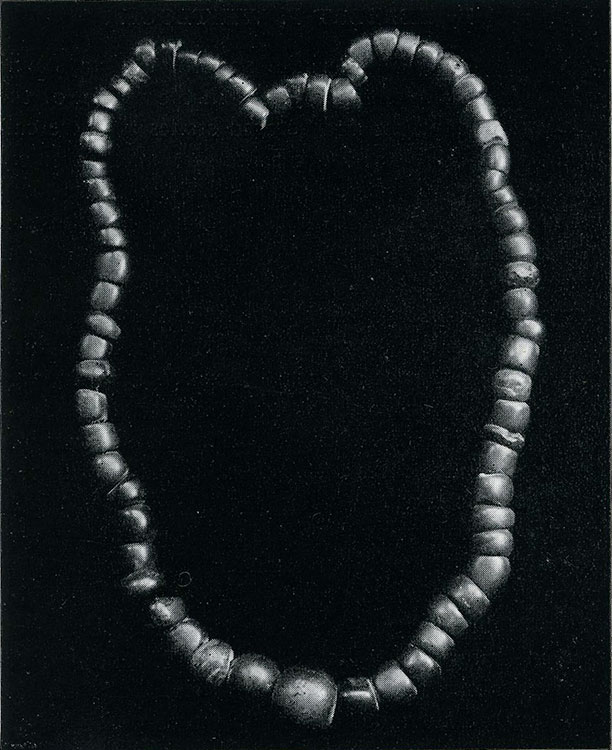

Ancient Amber Necklace. Such rough shaped beads as these, made from Baltic amber, were largely circulated throughout Europe in pre-Christian times. This necklace is from a grave in Hallstadt, Austria, and dates from about 300 B.C. (Morgan Gem Collection, A.M.N.H. Photo by Julius Kirschner)

Red gems, such as rubies and garnets, belong with fiery, passionate people. Among the medieval astrologists ruby was associated with Aldebaran, the red star, in the constellation Taurus, and garnet with the heart of the star group Leo. Many old legends make use of rubies and garnets indiscriminately as luminous stones, as instanced in the Talmudic story of the huge garnet which furnished light to the ark of Noah.

According to a Hindu folk-tale that recounts the birth legend of the ruby, this fiery stone was once a diamond whose color was changed to red by the life blood of a Maharanee slain in anger, disappointment and envy. The stone was subsequently placed as the red glowing eye in the image of Siva, the destroyer. The garnet was the favorite gem of Mary Stuart, that tragic queen whose life was swayed by passion, and whose blood in the end stained the headsman's ax.

Most primitive piece of jewelry

I once held in my hand the most primitive, if not the oldest, piece of jewelry that it has been possible to trace. It was a small group of garnet pebbles from the grave of a Bohemian woman of the Bronze Age, pebbles pierced so that they could be strung together, but each stone blazing with the rich fire that prompts the Bohemian peasant woman of today to desire these same red stones.

A Moslem Dagger. The Persian blade of Damascus steel is set in a jade hilt embellished with rubies by Hindu craftsmen, and is inscribed in Arabic rimed porse [prose]: "Thanks be to Allah. Praise be to Allah. Patience is of Allah." (Drummond Collection, A.M.N.H. Photo by Julius Kirschner)

Blue stones call to mind truth and constancy. There is something of divinity, something of heaven, in the deep blue of the sapphire or the opaque ultra marine of lapis lazuli. In the Veddic tale of the churning of the ocean, the sapphire was born from the last concentrated drop of Amrita, the drink of the Gods "whose shadow is immortality." And because this legend originated in India where Kashmirian or Singhalese sapphires must have been known in very early times, we have every reason to assume that the writer of the Rig Vedda referred to the blue stone that we know by that name. The sapphire mentioned many times in the older books of the Bible, on the other hand, was in reality lapis lazuli. This latter is the blue stone referred to in the Talmud legend as being the material upon which the ten commandments were engraved.

Many and various are the legends involving blue stones, but always their symbolism points to immortality, to divinity, to heaven. It is significant that the human-headed falcon that in Old Egypt represented the soul had its feathers beautifully inlaid with little slabs of turquois [sic] and lapis lazuli.

A Jade Ring Tray. The ladies of the Hindu harems, being themselves strictly confined, had no need to safeguard their jewel caskets with locks. Finger rings and toe rings were kept in dainty trays, such as this one, which was carved in China. (Morgan Gem Collection, A.M.N.H. Photo by Julius Kirschner)

The green color embodied in the emerald invariably calls to mind the verdure of spring; the budding of life; victory over the cold of winter; faith in the fruition of plenteousness which comes with summer. There is something kingly, something of power over mundane things, something steadfast in the symbolism of this gem. It dominates. By the early Christian writers, the emerald together with the green jasper was the one among the Apostle stones ascribed to Saint Peter. To quote from Andreas of Caeserea, "The jasper which like the emerald is of greenish hue, probably signifies Saint Peter, chief of the apostles, as one who so bore Christ's death in his inmost nature that his love for Him was always vigorous and fresh." This apostolic symbolism has persisted in the Greek Church from the fifth century to our own time. Recently I saw a beautifully executed cameo head of St. Peter carved in a splendid Russian emerald which was probably the work of an eighteenth or nineteenth century lapidary. As to legend, there is the wonderful story of the mighty emerald which dropped from Satan's crown when he fell from Heaven. Up to the beginning of our era the mystical history of this gem is shrouded in obscurity. It may have been the emerald which was one of the four stones possessed by King Solomon, and which gave him power over all demons. It became the San Graal, the cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper and in which later his blood was caught. From this legend emanated that remarkable cycle of myths which dominated romance of the Middle Ages; a veritable storehouse of symbolism.

Cleopatra's favorite

Emeralds were the favorite gems of Cleopatra, the embodiment of royalty and probably the most gem-bedecked queen of all time. Many of the green stones such as chrysoprase were often called, "victory stones" by the old writers. Such a one was reputed by Albertus Magnus as having been worn by Alexander the Great in his girdle.

A Persian Chalcedony Seal. The intricate and beautiful lettering engraved on this Mohammedan amulet form Arabic words taken from the Koran. It was worn suspended from the neck and protected the owner from ills, real or imaginary. (Morgan Gem Collection, A.M.N.H. Photo by Julius Kirschner)

The well known purple gem, the amethyst, as its Greek derivation indicates, was regarded as an amulet which would prevent intoxication. Dr. L. J. Spencer in his recent book, "A Key to Precious Stones," comments in a somewhat satiric vein on the use of this gem in episcopal rings. He says, "For this reason bishops, whose duties take them to public function of all sorts, wear an amethyst in the episcopal ring." Without doubt the medieval connection of the amethyst with Bacchus, god of the wine cup, comes from the story of the nymph named Amethyst one of those who followed in the train of Diana. Bacchus in order to fulfill a drunken vow was about to offer her to be devoured by the tigers that drew his car. The goddess in order to save her protégé from this horrid death, turned her into a white stone. And Bacchus, repentant of his cruelty, poured the juice of the grape over the stone figure, thereby dying it a rich purple.

The keynote of this birth myth is sorrow, repentance mingled with tragedy. And that is the feeling our minds associate with the color purple. More obvious is this color association when we consider the myth of Hyacinthus, the youth accidentally killed by Apollo, who caused a purple flower to spring from the ground where his life blood had been spilt. The purple gem which commemorated this sad event among the ancients was variously assumed to be either an amethyst or a purple sapphire.

Diamond lacks romantic mythology

When we think of a white stone we instinctively visualize a diamond, because this gem among the galaxy of brilliantly colored stones is notably without color. However, we should not attempt to analyze the appeal of the diamond in terms of its white color because it is the brilliance of its reflection that constitutes this appeal and not the color of purity and innocence which white suggests. The appeal of the diamond is one of ostentation, of blazonry, of display. In the Occidental world at least the wearing of diamonds belongs to a culture already well advanced, There are no European myths that link the diamond with romances of early centuries. It is by far too sophisticated, too hardly brilliant in its glitters to measure emotions in primitive terms.

For the true color imagery of the diamond, we must turn to the Hindu folk tale in which the first diamonds fell from the lips of Krishna, when in the form of a swan, he chose this means of rewarding an act of self sacrifice, charity and mercy. But the diamonds that constituted "Krishna's Gift" were not the scintillant gems of the Rue de la Paix, but Indian cut stones with little fire and sparkle.

In marked contrast to the cold glitter of the diamond is the warm serene glow of a pearl of fine luster. There is something of life, something vitally individualistic about pearls. It is as if the one who wore them wore part of herself suspended from her neck. The fabulous and much discussed draft of Cleopatra was not a meaningless gesture. She seemed to drink something that pulsated with her own vivid vitality.

Chinese Glass Beads. These are made from glass that has assumed an iridescent patina from having been buried for a long time. They were made in the Tang Dynasty (620–906 A.D.) and were found in a grave in Honan. (Morgan Gem Collection, A.M.N.H. Photo by Julius Kirschner)

And what of the opal? How can one analyze the appeal of color in something which has all colors and yet whose colors forever shift and mingle? My answer would be that this rainbow stone should be dedicated to such of us who, like great actresses, great musicians and great poets, have the gift of stimulating human emotions by our art.

Turning once more to the folk tales of India, there is one that tells of the wandering flute player, who, when he was summoned to the heaven of Indra, played his Golden Song before the congregation of the gods, and received as his reward for rendering them dumb with ecstasy, the Opal.

As to the tradition of ill luck that has become associated with the opal, it is enough to say that this hoodoo, together with those assigned to all the other so-called unlucky stones, is founded upon such a commonplace principle as the law of averages. Some of us remember a time when the proverbial "red-haired girl" was a rather rare sight, whereas horse-drawn vehicles were very common, and among them, one in every ten was sure to be connected with a white beast of burden. And thus originated the saying, "If you see a red-haired girl, you will immediately see a white horse," simply because the former was uncommon and the latter common. So it is with ill luck, that commonest of all human experiences, we are reasonably certain to find some uncommon possession with which to connect it. And if we do not happen to have an opal or a blue diamond, then our misfortune becomes just that.

When the woman of the twentieth century of our era dons her string of raw emeralds or aquamarines or lapis lazuli, she no doubt considers that her taste is ultra modern. Yet the women of the twentieth century B. C. wore much the same kind of necklace. Stroll through the Egyptian gold room in the Metropolitan Museum if you are curious to see what can really be done with roughly fashioned emeralds. Or notice the magnificent string of primitive necklace beads fashioned from old Persian lapis lazuli in the Morgan Hall of the American Museum. These things far transcend in barbaric appeal anything that has thus far been produced to meet the demand of ultra modern taste.

Forgotten stones

And there are many semi-precious stones used in the crude but very beautiful jewelry forms of long past eras about which we seem to have forgotten.

There are soft neutral colors in the agate beads of Merovingian France, and charm in the roughly rounded aquamarine beads that are still to be found in the bazaars of North Africa, and no one knows how old these are. Even such a prosaic thing as glass can be made a material of supreme though barbaric beauty, as anyone can testify who has seen Chinese glass ornaments of the early Han Dynasty.

If we must return to simplicity in our jewelry, by all means let us mould that simplicity along lines freed from the shackles of sophistication. If you must be barbaric, madam, why not select a classic model of barbarism?

The following image appeared in the original version of Whitlock's article; it was absent from the reprint.

Jade Neckpiece. This finely carved plaque, enlarged here to about twice actual size, was probably worn as a breast pendant or the central figure of a collar by a member of the mysterious Olmec race who lived in Mexico around the 10th century. Since no formal excavation has been undertaken in the Olmec area in southeastern Mexico, nothing is known of their beginnings or of their relations to other cultures. Traditions in the region often describe a highly civilized people by this name, but the Olmecs moved across the pages of history like mere shadows. That they may have differed in facial type from other tribes is suggested by the characteristic features which this piece, in common with the handful of other known sculptures ascribed to them, exhibits. (Loaned from a private collection, A.M.N.H. Photo by Charles H. Coles)

![A Moslem Dagger. The Persian blade of Damascus steel is set in a jade hilt embellished with rubies by Hindu craftsmen, and is inscribed in Arabic rimed porse [prose]: "Thanks be to Allah. Praise be to Allah. Patience is of Allah." (Drummond Col…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/531546a7e4b004de19791ef4/1500262544462-7F3GMZQLHFRD41XK7FXV/Dagger)