American Travels Of A Gem Collector, part 1

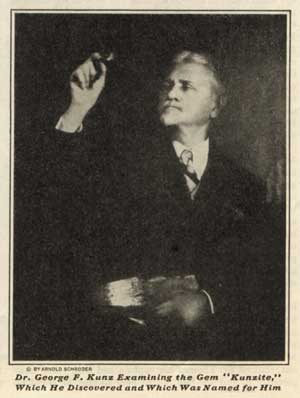

Webmaster’s Note: We are pleased to reprint the reminiscences of George Frederick Kunz (1856–1932), arguably the greatest gemologist the world has ever seen. At age 23, Kunz was appointed vice-president of the famous New York City jeweler, Tiffany & Co., a position he held for much of his life. But he is best remembered for his prolific writings on precious stones. Perhaps there is no greater testament to his work than the fact that many of his books have been reprinted and all remain in high demand in the collector market. Such works include Gems and Precious Stones of North America, The Curious Lore of Precious Stones, Magic of Jewels and Charms, Rings for the Finger, Book of the Pearl and Ivory and the Elephant.

According to mineral dealer, Lawrence Conklin, late in his life, Kunz granted a series of interviews to a reporter which appeared “as told to Marie Beynon Ray” in The Saturday Evening Post, as follows:

- American Travels Of A Gem Collector – November 26, December 10, 1927

- The Gem Collector in Europe – January 21, 1928

- Trailing Gems in Europe – March 10, 1928

- The Indestructible Value – May 5, 1928

These interviews, long out-of-print and practically impossible to acquire in their original format, are reprinted here verbatim, with the original illustrations. For those readers who wish to delve further into the Kunz oeuvre, see Lawrence Conklin’s The Curious Lore of George Frederick Kunz. In our opinion, the Kunz reminiscences are among the most readable and interesting in the realm of gemological literature. After having read them, we trust you will feel likewise.Part 1. Reprinted from the Saturday Evening Post, November 26, 1927, pp. 6–7, 85–86, 91.

To read Part 2 of this article, click here

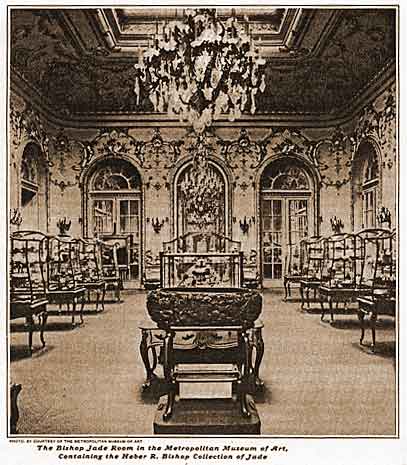

THE GREAT collections of gems are perhaps even more interesting in the making than in the seeing or the owning. At any rate, I should much rather be in possession of the experiences, adventures, travels and friendships collected while I was gathering what are often spoken of as the greatest gem collections of our time than of the gems themselves. I have made in all some dozen collections, including the J. Pierpont Morgan Collection, which is considered the finest in the world; the Chicago Exposition Collection, now in the Field Museum in Chicago, surpassed only by the Morgan Collection; and the Dr. L.T. Chamberlain Collection. Not the least interesting part of my work were the additions made to other men’s collections as, for instance, Mr. Clarence S. Bement’s, Mr. Heber R. Bishop’s collection of jade; Colonel Roebling’s collection, and many others.

And yet I, too, have set out in quest of gems, have known the thrill of pursuit and capture and, above all, the thoroughly satisfying experience of adding one rare gem to another in the ever-growing collections that even Time perhaps will not destroy.

A private collector is, of course, in a somewhat different position from mine. On the whole, things come more naturally to me, and I would not compare my adventures in search of treasure with those of men like Mr. Bishop, for example, who, not having agents all over the world at their beck and call, set forth themselves, not once but many times, to the far corners of the earth in search of some coveted bit – always, at that moment, the most coveted bit in their entire collection – and experience veritable Arabian Nights’ adventures by the way. And yet I, too, have set out in quest of gems, have known the thrill of pursuit and capture and, above all, the thoroughly satisfying experience of adding one rare gem to another in the ever-growing collections that even Time perhaps will not destroy.

In a Small Boy’s Pockets?

The beginning of this lifelong devotion to gems was in my childhood. You are to imagine one of America’s first meek attempts at a Coney Island – the tinny tempo of The Blue Danube being suffocated by a German band; little shrieks as hooped skirts billow upward and women’s feet clear the floor, bonnets askew, faces blazing; beyond the rough dance floor, tables on which mugs of foaming beer beat time to the music; and in the green and still beautiful distance, raucous yells from a ball field and the criers of those poisonously brilliant ices known as “hokeypokey, penny a lick; the more you eat the more you kick” – such were the Elysian Fields on the plains of Hoboken in the late 1860’s.

On the outskirts of the crowd pauses for a brief moment a small boy whose pockets bulge with lumpy mysteries. Even the ball game claims but a perfunctory glance and he passes along, on sterner business bent. Arrived at a secluded spot, he kneels and empties the contents of his pockets on the ground, sorting them carefully, muttering their names and an occasional affectionate word: “Good old quartz! Oh, you beauty! Fine bit of ore.” A litter of stones – not stones whose smoothness and roundness made them pleasant to the touch, not seashore pebbles picked for their glistening beauty, not small hard stones to fit neatly into the deadly sling shot. No, these delectable bits of shale and rock would have interested no other small boy, and no adult of his acquaintance would have given them house room. When away from home he trembled for their safety, tucked beneath his mattress, furtively hidden under loosened boards in the floor, concealed hither and yon like a squirrel’s hoard of nuts. All his holidays were devoted to collecting them, crawling at risk of life and limb over fresh excavations and down into new railroad cuts.

Every boy has his passion – his collection of stamps or coins or marbles or what not, and the only difference between another boy’s and mine was that I never outgrew it. Given a fresh excavation today, I am just as apt to go down on my knees and begin grubbing about as I was at the age of ten. Each one of those treasured stones contained its nugget of pure gold for me – its zeolitic minerals, green quartz, pectolite, iron ore; and I called them all by name as other boys spoke of their reals, their agates, their alleys and their pures. The Elysian Fields, the new excavation for the Bergen Tunnel, the many developments on Staten, Long and Manhattan islands, including the Fourth Avenue cut and the extension of the New York Central Railroad – all the pioneering engineering of our great city offered virgin soil to the collector of minerals – and a collector of minerals too poor – and too proud – to buy from dealers, I already was. I hadn’t acquired this passion from any acquaintances; I certainly didn’t inherit it, yet I can’t remember the time when I wasn’t solitarily and unbearably thrilled by the sight of a spot of ore in a bit of rough rock.

I first became conscious of this strange passion one day when, aged ten, I dropped into Barnum’s Museum on Ann Street and Broadway, opposite the old Astor Hotel, just a few weeks before it burned down. The collection of minerals formed by Mr. Bailey was on exhibition and I hung, suffocated with pleasure, over the cases. Since then my eyes have looked upon more wealth in gems, I suppose, than any other living eyes, yet nothing has ever seemed to me more thrillingly beautiful than those not-even-precious stones in old Barnum’s Museum. The only person who even understood this curious passion of mine was Mr. Benjamin Chamberlain, a man when I was a boy, who devoted twenty-five years to making the finest collection of minerals from Manhattan Island ever gathered, a collection that is now in the Museum of Natural History.

Every boy has his passion – his collection of stamps or coins or marbles or what not, and the only difference between another boy’s and mine was that I never outgrew it.

Acclaimed

Shortly after the Barnum Museum fire my family moved to New Jersey and I was able to start collecting minerals from the vicinity of Bergen Hill and the Elysian Fields, gradually, as I grew older, extending my excursions to include Franklin, Staten Island and New York City. At the age of fourteen I started sending specimens abroad for exchange, and had already begun that unending stream of correspondence on mineralogy which now inundates the vaults of several museums, the cellars and several of the rooms of my home, my private offices, and heaven knows what outlying territories. It all seems to me very interesting and important, though I suppose its custodians would gladly see it heaped in a pyre on the Mall of Central Park, its flames licking the sky.

Between working days and studying nights at Cooper Union, with a few holidays in the summer, I managed to complete my first collection, and whatever else may be said of it, it was, from the point of sheer bulk and weight, the most considerable I have ever made. It contained 4000 specimens and weighed two tons! It now became my great and consuming ambition to sell this collection, not so much for the money it might bring but to mark myself in the eyes of the world as a real collector.

Between working days and studying nights at Cooper Union, with a few holidays in the summer, I managed to complete my first collection, and whatever else may be said of it, it was, from the point of sheer bulk and weight, the most considerable I have ever made. It contained 4000 specimens and weighed two tons!

Of course such collections are of value only to museums, their interest being purely mineralogical and geological. A mineralogist collects everything that Nature produces, and those things with the least commercial value often have the greatest value in his eyes. Already my collection was so good that I was able not only to exchange abroad but even to sell duplicates here, some to Dr. Harvey Wiley, the pure-food expert; and when I finally received an offer of $400 for the lot – it was, of course, worth much more – from the University of Minnesota, I was smothered in pride. Not I think, when I received the honors of Officier de la Légion d’Honneur, of a Knight of the Order of St. Olaf, or Officer of the Order of the Rising Sun of Japan, did I experience the same thrill as on that day that officially placed me among recognized mineralogists. [This jade bowl pictured in the top photo is now in the collection of Pala International.]

Not all my childhood was a delectable grubbing for minerals. I remember less passionate but not less happy hours spent in walks – before we moved away from New York – with my father, who was a great lover of Nature, in search of various wild flowers through the fields and lanes and little wooded stretches of New York City. Everything north of Forty-second Street was an open cut, and at Fifty-ninth Street the city broke into a turbulent wilderness. Below that, one house to a block was a good average, horse cars and carriages were the only means of getting about, and it took three-quarters of an hour to go from Canal Street to Fifty-ninth.

Then, in Jersey, I had a playground it would be hard to beat – one that had cost almost $5,000,000. At the foot of Third Street in Hoboken lay the bulk of one man’s magnificent but impractical dream. In 1861, when the war broke out, Edwin Stevens, founder of the Stevens Institute of Technology, had a beloved daughter in the South. He couldn’t face the torture and suspense of being separated from her during the uncertain duration of the war, nor any perilous attempts she might make to win her way north. So, like the lordly gentleman he was, he built her a ship of her own to sail south for her and carry her home in triumph. No ordinary passenger ship was this – no gentleman’s pleasure yacht – but, killing two birds with one stone, this amazing man – who feared as much for the safety of New York as for that of his daughter, and always maintained that any properly guarded enemy ship could enter the harbor and blow us to pieces – built a submersible gunboat for our defense.

A mineralogist collects everything that Nature produces, and those things with the least commercial value often have the greatest value in his eyes.

Alas, though at his death he left an extra million to complete it, it was never finished and was finally scrapped and sold in 1875 for $55,000, never having fired a shot in defense of the city. When I was a lad it was the $5,000,000 playground of the Stevens boys and their friends, and better caves, mines, pirate holds or thieves’ dens I defy any boy to find. They had no luck with their boats, those Stevenses. There was an earlier Stevens who built a single and double propeller boat before Robert Fulton built his, but the name of Fulton, not that of Stevens, is the one that has come to be commonly associated with early steam navigation on the Hudson.

Why are They Precious?

I made other mineralogical collections after that – better if not bigger – and sold them to various museums, so that it was natural that I should eventually become connected with the Museum of Natural History in New York, which at that time modestly occupied two floors in the little old red brick Arsenal Building in Central Park. Later I was offered the directorship of the National Museum at Washington, but I had already begun to look in another direction. I wanted to continue working at one thing only as long as I felt I could better myself, and though I still employed my leisure in studying mineralogy and chemistry I had become interested in another phase of the science.

At that time the jewelry profession was strictly confined to precious stones, of which there are but four – the diamond, ruby, emerald and sapphire – and – not a stone but none the less precious – the pearl. These were, as a matter of fact, the only gems that were really seriously considered, although cameos had a certain less solemn vogue, as also the onyx and bloodstone. Up until the middle of the nineteenth century, coral, opal and turquoise had been considered precious gems, but due to the change in fashion, to the great quantities of inferior material put on the market and to increased understanding of the nature of gems, they had by this time been ranked with the semiprecious gems.

Now in my mineralogical investigations I had from time to time come across many beautiful minerals that had all the qualities of gems, being of great hardness, tenacity, brilliancy, transparency, purity and exquisite coloring. Cut and polished, many of these stones rivaled in beauty the precious stones. They were indeed, in every acceptance of the term, gems, even though denied the epithet “precious.”

This question of preciousness is an interesting one. Just what is it, I am often asked, that ranks a gem as precious? What excludes it? It is no one quality but a combination of several. The opal may certainly lay claim to be as beautiful as the ruby; yet the ruby is precious and the opal is not. The zircon is as brilliant as the diamond, yet not precious. The beryl is as hard as the emerald, yet not precious. The tourmaline is as durable as the pearl, yet not precious. The hiddenite is more rare than the sapphire, yet not precious. Here are the prime qualities that determine the rank of a gem – all of them possessed by stones ranked as semiprecious. But preciousness is like the beauty of a face it is not alone a fine pair of eyes or a lovely complexion that constitutes beauty, but a combination of several qualities.

At that time the jewelry profession was strictly confined to precious stones, of which there are but four–the diamond, ruby, emerald and sapphire – and – not a stone but none the less precious – the pearl.

Therefore it is only when a gem possesses to the nth degree, first, hardness – the principal qualification – then brilliancy, then beauty, then durability, then rarity, that it is given the brevet of preciousness. As in a horse or a dog, it is a question of the highest number of points. That is why the diamond outranks all other jewels. It really possesses the qualities of all other stones – the greatest hardness, an unsurpassed brilliancy, an unrivaled beauty – due to its play of color and its fire – an unexcelled durability and extreme rarity. But, above all, it is its supremacy in hardness that places it beyond all other stones. It is the hardest known substance on earth and, as far as we can judge, on any planet.

Rubies and sapphires come next in hardness – they are one and the same stone, except for the coloring matter – and emeralds rank third, being, even though third, yet so hard that nothing will scratch them but a precious stone.

The pearl stands alone. The diamond is king, the pearl, queen – with just that touch of feminine frailty that is part of a woman’s charm. For the pearl is less hard than many even of the semiprecious stones; yet – again like a woman – it has as much endurance as the masculine gems. I have myself tried its feminine durability by the severest tests. I once took a number of pearls weighing two grains each and, placing them on pine, oak, mahogany and rosewood boards, pressed them in with my heel, and none of them was broken or scratched, though they sank clean into all the boards, with the exception of the rosewood, into which they sank only halfway. It is this quality of the pearl that raises it unquestionably above the opal, which is more or less fragile.

In those early days, as I have said, no so-called fancy stones were on sale in any jewelry store in the country; one could scarcely find them in a lapidary’s shop, yet, reviewing those that I had gathered, it seemed to me that many ladies, even those who could afford the gesture of diamond tiara and pearl choker, would be happy to array themselves in the endless gorgeous colors of these unexploited gems. As I looked over a collection of them, with the sunlight imprisoned in the sea-green depths of the tourmaline, lapping at the facets of the watery blue aquamarine, flooding the blood-red cup of the garnet, glancing from the ice-blue edges of the beryl, melting in the misty nebula of the moonstone, entangled in the fringes of the moss agate, brilliantly concentrated in the metallic zircon, forming a milky star in the heart of the illusive star sapphire – how, I thought, could a woman ever resist their subtle appeal?

A New Gem

So one day, buckled in youth, I wrapped a tourmaline in a bit of gem paper, swung on a horse car, and all the way to my destination rehearsed my arguments. Arrived there, I was finally received by the managing head of what was even then the largest jewelry establishment in the world, and showed him my drop of green light. I explained – a very little; the gem itself was its own best argument. Tiffany bought it – the great dealers in precious stones bought their first tourmaline from me. The check which crinkled in my pocket as I walked home in the late afternoon, forgetting there were cars, stargazing, tripping over curbs, meant very little in comparison with the fact that I had interested a foremost jeweler of that time in my revolutionary theory and made the acquaintance of a man who was later to become my close friend.

So one day, buckled in youth, I wrapped a tourmaline in a bit of gem paper, swung on a horse car, and all the way to my destination rehearsed my arguments. Arrived there, I was finally received by the managing head of what was even then the largest jewelry establishment in the world, and showed him my drop of green light.

Thereafter I sold Tiffany’s many other semiprecious stones. Then one day came the offer to join the firm as their first gem expert, and ever since I have held that position. In those first days very naturally a large part of my interest was engaged in this problem of discovering and introducing, one after another, as the public gradually became interested, these lovely, unknown semiprecious stones in which no jeweler of the time was even slightly interested. Of course, with the backing of such a firm I was in a commanding position to do this. Naturally, at first the public was skeptical. I not infrequently heard such withering remarks as: “A zircon? What’s a zircon? It’s just an imitation stone, isn’t it?… You mean it grows like that?… Oh, no, thank you, I’d feel as if I were wearing something false.” Or, “Well, of course it’s pretty, but I’d feel like a gypsy. I’d just as lief wear a lump of colored glass. It has no real value.” And the poor little blob of sunlight would dwindle in my palm till even I had some difficulty in maintaining my respect for it – the zircon that today sells as high as forty dollars a carat and a single fine gem of which has brought as high as $2000, not to mention the tourmaline, fine examples of which sell for thirty dollars a carat, and a very fine cat’s-eye for more than $100 a carat.

A Crystal Rainbow

Bucking public opinion, or rather, prejudice, is a heartbreaking task when it touches people’s purses. However, in those early days I had some encouragement. I invariably found that it was those who eared least for money and most for beauty – in other words, artists – who needed no persuasion to my way of thinking. It was sufficient to show a handful of these lovely things to a lover of color to hear unstinted praise of my pets. I remember once showing some of these gems to Oscar Wilde, who was himself a connoisseur and had a not uninteresting collection of his own.

“But, my dear Kunz,” he said, “these are exquisite, charming! I believe I admire them even more than the precious stones for among them, except for rarities, we have only the four obvious colors, but here – why, there’s not a color on land or sea but is imprisoned in one of these heavenly stones! What wonderful jewelry could be made with these subtle phrases of color such things as only the ancients and the barbarians made – work of Egyptians, Persians, Greeks and Romans – such beauties as we moderns have never conceived. My dear fellow, I see a renaissance of art, a new vogue in jewelry in this idea of yours!”

“And for those of conservative taste these stones can be as handsomely mounted in present-day settings as the precious stones,” I added.

He snapped his fingers, shook that mane of hair.

“Bah! Who cares for the conservatives! Give them their costly jewels and conventional settings. Let me have these broken lights – these harmonies and dissonances of color. Can you price beauty by the carat?”

Helping the Movement

That was an artist’s point of view, and Wilde, whatever his faults, was an artist. And that prophecy of his concerning a new genre of jewelry, which I had only vaguely sensed at the time, has come amazingly true. Not the least popular cases in the great jewelry shops of today are those where the fantasy of the artist; escaping from the conventionalities of platinum and precious stones in their delicate frost and lacework designs, runs riot in turquoise amethyst, tourmaline, topaz, chalcedony, peridot, baroque pearl, rose quartz, obsidian, sunstone, amazonite, coral, opal, starlite, lapis lazuli and a hundred other once rare but now quite usual gems, worked not only with platinum but also with that metal of many shades – gold. And no lady with a quarter of a yard of diamond and emerald bracelets up her arm or three yards of Oriental pearls about her pretty neck would today scorn a great star sapphire for her finger or a beryl bracelet for her less formal moments.

It’s odd and amusing how sometimes a little, inconsequential accident somewhere in the world will give impetus to some distant movement, just as a sudden shock of sound sometimes precipitates an avalanche. About the time I was most worried about the launching of this new vogue in gems the Duke of Connaught, way off in England, took a fancy to marry and, without fear and without reproach, selected for his fiancée, not the conventional and lordly diamond but a humble little cat’s-eye. Well, when the Duke of Connaught can do that – With that as an opening wedge, I soon found greater favor for my hyacinths and my jacinths, my jasper and my jade.

Now, when it comes to semiprecious stones, America is not so poor a country as one might imagine. We are no great shucks so far as the precious stones are concerned, though they are all four, and the pearl, found in not-to-be-sniffed-at quantities within our borders. Strange that when Columbus sailed all the way to the New World to open up a new India, richer in precious stones than the old, we should have turned out to be the poorest of all the continents in this kind of wealth. However, when it comes to the semiprecious stones there is not a state in the Union that can’t hold up its head. About the time I was making my initial efforts to launch these semiprecious stones commercially, the United States, awakened by the Centennial collections, began to take an interest in itself mineralogically and to institute scientific researches for gems. Naturally all this helped my cause and I, too, began to go out upon those excursions of exploration and discovery that have acquainted me so thoroughly with the gem resources of America. From that time on, for twenty years I was in charge of the precious-stones department of the United States Census, visiting practically every state in the Union.

Gems In Your Dooryard

I think that we in America don’t realize in what close proximity we are all living to buried wealth in gems. Do you, Mr. Maine, know that some of the finest tourmalines in the world are found not a hundred yards from your doorstep in the vicinity of Paris? Do you, Mr. North Carolina realize that the second largest emerald in the world was found within a few hours’ ride of your home? Have you ever heard Mr. California, that a beautiful green gem named for you was discovered in your back yard and that two other brand-new gems, never before heard of, were discovered in your own mountains? And you, Mr. Montana, do you know that sapphires are found in your back yard, and you, Mr. New York, do you know about your beryls; and you, Mr. Utah, about your topazes and your garnets? Not one of you but has some beautiful and valuable gem close at hand, often several. Have you heard the story Mr. New Jersey, of your famous pearls? Of one in particular, the most famous of all? Quite a romance.

The first awakening to the value of freshwater pearls in America – which, by the way, though ordinarily less lustrous and therefore less valuable than Oriental sea pearls, bring extremely high prices, occasionally up to $16,000 apiece – came in 1857. A shoemaker of Paterson, New Jersey brought home a mess of mussels from one of his regular excursions for shell fish in Noteh Brook which he proceeded to fry with the usual abundance of grease. As he took one of the succulent bits into his mouth his teeth closed on a hard round object which he was later informed by an authority was a pearl weighing 400 grains and which, had its beauty and luster not been destroyed by heat and grease, would probably have proved to be the finest pearl of modern times, worth doubtless more than $25,000. This was also probably one of the most expensive dinners of modern times.

So then the hunt was on, and men, women and children with trousers and skirts rolled up went wading in the shallow waters of the little stream for the wonderful pearls that must surely be there, for no belief in the world, except the gambler’s belief in the next turn of the wheel, is stronger than the gem hunter’s belief in his find Lost hours and years are counted as nothing when, or if, finally the illusive gleam drops into his palm.

And then one evening a New Jersey carpenter, sitting at his fireside, opening the oysters he had gathered that day, gave a little cry and jumped up, holding in his hand something that shone with the unmistakable effulgence of the true pearl – a frighteningly large pearl. Almost as soon as he found it, after he and his wife had taken one long, seared look at it, he hid it, and slept not at all that night. The next day at dawn he hitched the oxen to his cart, and crossing the river on a ferry, came riding slowly and solemnly through the streets of New York, not so strange a sight in those days, though queer enough, as it would be today.

The Vanished Queen Pearl

At that time there was but one possible destination for so rare a find, and straight to Tiffany’s, then a low brick building on the corner of Chambers Street and Broadway, our epic carpenter rode, hitched his team outside and strode, leaving sly clerical smiles in his wake, down the aisles to the president’s office. Wonderfully enough for he would open his palm to no one else, he saw the president, who for the moment was only less frightened than the carpenter. For a true pearl of monstrous size, beautiful luster, and exquisite pink color it undoubtedly was; but the president’s fright was of a somewhat different nature from the carpenter’s. A true pearl of great price! But suppose where it came from – not seventeen miles from where he sat – and in other streams of this wide land, there should now be found dozens, hundreds, thousands like it – what then of the price of this great pearl?

Here were both a promise and a threat. Here were a financial problem and one of ethics. If there were but the one, this pearl might be worth to him and the carpenter almost anything; but if, as was more likely, there should be great numbers it might be worth very little to them.

“Tell me about this pearl,” he said slowly.

The carpenter shuffled.

“I found it in Noteh Brook yesterday,” was all he found to say, adding nothing to the sum total of the president’s knowledge. Then he added suddenly: “My wife and girl want some jewelry.”

The president smiled. He paused another moment for an equitable adjustment and then said, “I’ll pay you $1250 in cash for this pearl and give you $250 more in trade. Does that satisfy you?”

The carpenter shuffled his feet in satisfaction and together they passed out into the showroom to select the jewelry for the wife and girl.

And so the great Tiffany Queen Pearl, weighing ninety-three grains – few, if any, ladies in America today have a pearl of that size in their necklaces – came into the market. It was sold first to the lovely Empress Eugenie, later came into the possession of Herr Hansel von Donwermark the great industrialist of Germany, and then suddenly disappeared. To whom it was next sold is not known, nor where it is today, but doubtless somewhere in Europe, as it is seldom that great gems pass out of existence. They may be for a while among the missing, and then suddenly they turn up in some unexpected place. It is just possible that this mention of it here may bring us some word of this missing pearl. To its story we have only to add that, although pearls amounting to $300,000 were eventually found in Noteh Brook by the hordes of visitors and local laborers who rushed there, no others of its size and beauty were ever brought to light, making this an important item in American gem history and its present value, if it is still alive, about $10,000.

“Tell me about this pearl,” he said slowly.

The carpenter shuffled

“I found it in Noteh Brook yesterday,” was all he found to say, adding nothing to the sum total of the president’s knowledge. Then he added suddenly: “My wife and girl want some jewelry.”

The president smiled. He paused another moment for an equitable adjustment and then said, “I’ll pay you $1250 in cash for this pearl and give you $250 more in trade. Does that satisfy you?”

The carpenter shuffled his feet in satisfaction and together they passed out into the showroom to select the jewelry for the wife and girl.

And so the great Tiffany Queen Pearl, weighing ninety-three grains – few, if any, ladies in America today have a pearl of that size in their necklaces – came into the market.

Pearls Before Swine

Though this one important pearl came from New Jersey, Noteh Brook is completely overshadowed as a pearl fishery by a dozen other sources within our boundaries, and many extraordinary pearls, some even more valuable than the Queen, have in the past sixty or seventy years come from our waters. A negro near Marley, Illinois, found – not while pearl fishing but while raking over the muck of a hogpen where the discarded mussels had been thrown as feed – a pearl weighing 118 grains for which he received $2000 from a St. Louis buyer and which was later sold for $5000. This was literally a case of casting pearls before swine. A pearl weighing 103 grains, found in Arkansas, was sold for $25,000 and one of 68 grains, found in Wisconsin, was marketed at $15,000, and there are many others. When a simple American pearl can bring such prices as these it isn’t difficult to figure to what prices may run a two-yard necklace of many strands of perfectly matched Oriental pearls. There is one necklace I know of which is valued at $1,000,000.

When the pearl fever strikes, it is like a pestilence. Thousands go down before it and whole sections of the country are swept bare of humanity. Crops wither, villages are deserted, and learning languishes as the countryside is drained of its labor, diverted to the new get-rich-quick fisheries. More than once I have visited these fever-ridden districts in quest of scientific data rather than of pearls, for the important buyer need never go out in search of his game; it finds its way with great alacrity into his net. But merely for my own satisfaction I went to one after the other of the most important of our pearl fisheries.

I remember when the Arkansas pearl fever broke loose in 1896. As seems usually to be the way in a place where pearls have always been known in small and unimpressive quantities, the lovely gems were given to the children as playthings – “See pretty bead!” – and rolled about the floor and stuffed down dolls’ throats, and even carried about by the adults as lucky stones. But in 1896 all that was changed, for quite suddenly many large and rich pearls were found in the White River. Trouser pockets were searched, tea canisters turned out button bags emptied, children robbed of their playthings to recover the beads that might now turn out to be of untold value. Farmers deserted their plows, schoolteachers closed their doors, shoemakers left their benches, and all Arkansas turned to pearl fishing.

A negro near Marley, Illinois, found – not while pearl fishing but while raking over the muck of a hogpen where the discarded mussels had been thrown as feed – a pearl weighing 118 grains for which he received $2000 from a St. Louis buyer and which was later sold for $5000. This was literally a case of casting pearls before swine.

There I saw thousands of people daily fishing the waters of the Black and White rivers, putting out in any kind of craft with any kind of implement they could get their hands on. I frequently saw several hundred people, all intent on making a fortune in the next half hour, their faces flushed, their hands fairly shaking with excitement, congregated at one bar or racing like madmen to the spot where the latest find had been made. The children, on an indefinite holiday, were often as fortunate as their elders and brought up many lustrous, beautiful gems. It was as though the Stock Exchange had suddenly, one fine morning, decided to open on the river. The result was that in three years, more than $500,000 worth of pearls were found. Yet it has been estimated that if the total amount of money realized for pearls in America were divided by the number of men and days invested in their search, each man would have earned not more than a dollar a day. However, not this man but he who finds in his first shell a pearl worth $1000, is the one upon whom all eyes are turned.

Another valuable pearl locale is Wisconsin. Several million dollars’ worth of pearls have come on the market from Southwestern Wisconsin – pearls remarkable for their beauty, luster and diversified coloring. In 1901, Tennessee was the scene of a pearl rush – a rush having all the thrill, picturesque quality, adventure, and pathos of the Klondike affair – easy-going, pleasure loving people of the happy-go-lucky sort who give up steady positions and sure incomes for the uncertain profits of a rush, living in tents and shanties or newly built house boats along the banks of the Clinch River, subsisting on the fish they catch, dancing and singing at night around camp fires to the music of the banjo, and hurrying off every Saturday afternoon to the nearest town to sell their catch of pearls. Ohio and Iowa have likewise contributed importantly to the pearl industry, and in all about $15,000,000 worth of pearls have, in the past seventy-five years, been realized from American sources.

In the main, wherever we have limestone soil and a river we are apt to get pearls. One of the finest necklaces ever assembled from American pearls was that matched by Tiffany in 1904. This was later exhibited at the St. Louis World’s Fair, sold to a London merchant, and finally purchased by a Spanish nobleman for 500,000 francs This necklace consisted of thirty-eight pearls weighing 1710 grains, an average of 45 grains for each pearl. The central gem, however, weighed 98.5 grains and the rest were graduated down to the last of 20 3/8 grains. A ninety-eight-grain pearl would be about half an inch in diameter. Of course, as pearl necklaces go, this one is nothing so extraordinary, for frequently Oriental necklaces of that length are valued at $500,000. It is impossible to assemble a perfect or almost perfect pearl necklace from American pearls, as they are not sufficiently uniform in color, though very fine necklaces have been made here.

Richer Than a Gold Mine

To the Morgan Collection, as well as several others, I added pearls which I obtained from these interesting sources; for I felt that the finest Oriental specimens would not make up for the absence of pearls found in our national streams.

Perhaps it’s because of my close association, through the United States Census Bureau, with American gem localities, perhaps it’s because of my many opportunities for studying gem mineralogy at first-hand here, or perhaps it’s just my natural prejudice, but my travels through the United States in quest of gems and gem lore have always been more interesting to me than my travels anywhere else in the world. I can’t speak here of all the gem mines from coast to coast and from Canada to Mexico which I have visited – some of them eight or more times – and whenever possible immediately after their opening but there are some that won’t bear slighting.

To the layman it would perhaps seem improbable that, sitting at a desk in New York, one should be able to discover a gem mine in Montana; yet that is just what happened to me once.

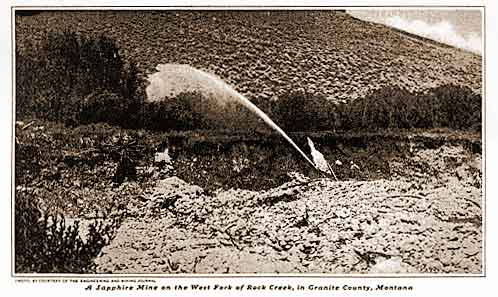

One day some years ago I received by mail – which reminds me that the Cullinan diamond, which one would naturally expect would journey under armed guard, was sent for safety all the way from the Premier mines in Africa to London by ordinary registered mail – one day I received some specimens in which occurred grains of gold. These had been mined in Yogo Gulch, Montana, on a property bought as a gold mine. As a matter of fact very little gold was ever located there. But among these specimens I found certain crystals to which little attention had been paid, but which, on examination, I discovered to be fine blue sapphires. When this information was conveyed to the owners they immediately began to search for other specimens, and soon brought to light the fact that, in purchasing a mere gold mine, they had acquired the most valuable sapphire mine in America, yielding more wealth than all the other sapphire mines in America put together – and a finer quality of gem.

Size and Not Perfection

I later visited these sapphire mines and noted the peculiar way in which Nature had aided the miners in tracing these veins of sapphire-bearing rock. Certain portions of the rock, not more than two or three feet wide were everywhere bored into by that too prevalent pest, the prairie dog, in his search for a home. Wherever the rock had undergone an alteration that softened it sufficiently for the gophers to enter it, there, the engineers found, was a sapphire bearing vein. By means of these despised gophers the vein was traced for nine miles across the country. An English company bought six miles of these veins and is still mining the sapphires in quantity. There will be sapphires for fifty years to come in Montana. These sapphires are of a peculiar quality. The Oriental are larger and finer, but the American are of beautiful quality and hold their color at night – an important point – better than any sapphires except those found in Ceylon. They have sold as high as $100 a carat. Up to the present time this mine has produced more than $10,000,000 worth of sapphires.

One hears a great deal of the size and magnificence of the jewels in the possession of Oriental and Russian potentates, and certainly many of these famous jewels are as fine as they are large; but not so many as we in the West are apt to believe. The greatest part of the wealth of the world in gems today is right here in America – an astounding proportion of it; I should say between one-third and one-half – and we not only possess the greatest quantity of gems and the largest proportion of big ones, but our standard of quality is far higher not only than that of the East but even of Europe.

Many of the celebrated gems of the East are stones which an American lady would not buy, let alone wear. Some of the emeralds in the Russian crown jewels, for example, instead of being what is properly termed a gem, are the whole large crystal – that is, when an emerald crystal some four inches long is found, some of the foreign lapidaries will facet and polish the whole enormous thing, although it may be uneven in color, with fissures and inclusions. It is the size that impresses them, and one overpowering stone of not very good quality appeals to them more than a small but perfect jewel. A more discriminating taste demands that the one beauty spot in that great crystal – the tiny, unflawed, intensely green bit that constitutes the true emerald be cut out for use as a gem and the rest discarded. That is why emeralds, if they approach perfection, can command almost $1,000,000 an ounce – not a high price when one realizes that perhaps only one ten-thousandth part of the original crystals cut to produce that ounce is here represented. However, no stone varies more in quality – from the most worthless at $5 a carat up to gems worth well over $5000 a carat. A warning to the amateur buyer to watch his step.

There will be sapphires for fifty years to come in Montana. These sapphires are of a peculiar quality. The Oriental are larger and finer, but the American are of beautiful quality and hold their color at night – an important point – better than any sapphires except those found in Ceylon.

America produces some very fine emerald crystals. I have visited the emerald mines in North Carolina many times and obtained wonderful specimens for the various collections I have made. I was particularly interested in these mines, as a friend of mine, Mr. Stephenson, was chiefly responsible for the discovery of emeralds in that state. If other public-spirited men throughout the country would devote themselves as whole-heartedly to the exploiting of the natural mineral resources of their part of the country as he did, perhaps many other such discoveries might be made. For more than twenty years Mr. Stephenson conducted widespread investigations for local minerals. When he began, the county was mineralogically a blank. He, an amateur mineralogist, offered rewards to all the farmers for miles around who would bring him interesting specimens of minerals.

The Romance of the Squid

Thus he discovered, among other things, some lovely grass-green beryl; and finally, as he urged the farmers to intensify their search for clear and perfect specimens of dark-green beryl – the emerald – he brought to light many veritable emeralds, among them one of the most famous emerald crystals in the world. This crystal, which originally belonged to Mr. Stephenson, was eventually placed in the Bement Collection. This remarkable emerald has only one rival in the whole world – the famous Duke of Devonshire emerald, which is only a quarter of an ounce heavier. Our American emerald weighs nine ounces and is eight and one-half inches long. A second crystal of five ounces I added to the Harvard Collection, and other very beautiful ones to the Morgan Collection, the British Museum and the Imperial Museum in Vienna. Yet, though the mines were at first worked with flattering success, in the end they did not prove financially profitable.

Tourmalines I drew primarily from two sources, adding them to the Morgan Harvard and other collections. And here again one sees what the enthusiasm of one man has done and can do again in the future if, like Mr. Stephenson, he will devote time and energy to the work and above all arouse the interest of the farmers in the resources of their own fields and hills. Not all the emeralds and tourmalines in America have yet been discovered. Wealth may still lie at our back door and any day a new vein of gems may be opened up by the native who searches earnestly and intelligently. A nephew of Elijah L. Hamlin devoted the entire spare time of his life to gathering the wonderful tourmalines his uncle had originally discovered near Paris Maine; eventually amassing a collection so important that part went to the American Museum of Natural History, but the greater part to Harvard. One of the most interesting types of tourmaline here discovered is that which looks for all the world like a miniature watermelon – green on the outside and, when cut open, white and then watermelon pink on the inside. Nothing is lacking but the black seeds.

It’s not always the most valuable stones that are the most extraordinary. Agate for example. Here is a stone which, but for a peculiar property it possesses, would scarcely be considered a gem. It comes in such huge masses from so many liberal sources that, like alabaster or porphyry, it is commonly used for decorative purposes; but there’s a certain proportion of it which, unlike any other stone, can be transformed to something lovely enough to be called a gem.

Not all the emeralds and tourmalines in America have yet been discovered. Wealth may still lie at our back door and any day a new vein of gems may be opened up by the native who searches earnestly and intelligently.

I don’t know of any drama in Nature more interesting than that of the agate – the agate and the opal, for they are one and the same stone, the opal merely containing more water – about 5 per cent – and therefore being less hard. So many centuries and so many upheavals of Nature – volcanic eruptions, Cretaceous periods, sinking of continents, removals of mountains – have gone into the making of the jewel that a lady wears so carelessly in her ear. “Pretty thing,” she thinks, and that’s the end of it.

Pretty thing! There’s the opal on her little finger, for example. Look at it, madam. Once a live fish wiggling joyously through crystal waters: but a world-rocking invention which man has just recently developed was conceived by this clever little squid some aeons ago. He is shooting merrily through the water. Suddenly danger appears – a bigger fish, headed murderously in his direction. Instantly the little squid squirts a flood of inky liquid into the water and under cover of its murkiness, like our modern man-of-war in its smoke screen swiftly escapes.

Well, when, one place and another, the waters of the earth dried up, millions of these little squids were left gasping on dry land. Then came convulsions of Nature; gases were belched forth, lava streamed out, volcanoes erupted, heated waters spouted, rocks were hurled forth; and the little squid skeletons were caught in the lava and embedded in the rocks. So then the heated waters containing soluble silica came creeping over the rocks and began to eat their way into the bones of the squid, mingling with the lime, with which they had a natural affinity, rather than seeping into the harder rock. Slowly throughout the centuries the waters ate away the bone forming a deposit which leaped in the sunlight like living fire – the opal. Sometimes, when there was not a bit of bone or wood or shell embedded in the rock, the waters found a crevice – a narrow opening leading to a wider cavity. The gases and boiling waters trickled through this crevice, depositing silica. Gradually the narrow neck of this natural rock bottle was closed by these deposits, and today, when we find one of them, it is completely sealed over. But shake it and you will hear those century-old waters aswish inside. Smash it, and there, lining the bottle with beauty, is the jewel agate or opal. In New South Wales much opal was thus formed, and in Yellowstone Park, Oregon, and other places in the United States agate was so deposited.

Drawn in its Own Ink

Oh, but about the squid! Not all of them underwent this divine transfiguration to gems, and many remained as fossils in the rock. I picked up a whole cigar box full myself in Jersey, for New Jersey, parts of which were once a sea, had its Cretaceous period, and near Freehold, for example, one can find today shark’s teeth, sea-reptile skeletons – some five feet high – and other remnants of sea life, making this soil unusually rich for agricultural purposes. And last act in the drama of the squid: A naturalist recently opened the bone of one at the place where the ink with which it clouded the waters was concealed, and there found a minute deposit of black powder. With this powder, merely adding water, the naturalist re-created ink and drew a picture of the squid in his own ink – ink thousands of years old. This same little squid – cuttlefish or devilfish – is still a favorite food among the Italians.

Look again at your opal, madam. Isn’t it now something more than just a pretty thing?

The opal, though of the same chemical composition as the agate – barring the higher percentage of water – is much more beautiful and, like the cat’s-eye, star sapphire, moss agate, and a few other gems, is never faceted; merely cut and polished. I think it is the favored stone of most artists, who delight in its unmatched play of color. But the agate – the less attractive of these two sister stones – makes up for this by the peculiar property of which I spoke. You know those exquisite cameos that come down to us from the ancient Greeks, marvels of the lapidary’s art, a delicate goddess’ head, perhaps, carved in white on a marron ground? The agate transformed!

Look again at your opal, madam. Isn’t it now something more than just a pretty thing?

One of Nature’s Masterpieces

This stone is built up by Nature in layers, alternately pervious and impervious, and this characteristic the ancients discovered. Onyx, consisting of one black and one white layer, does occasionally exist in Nature, and this was doubtless what was first used for cameos. But later lapidaries discovered that if certain agates were boiled in sugar and water or blood and water till the pervious layers had become saturated, and then immersed in sulphuric acid, the liquid drawn up into the stone would turn a velvety black, thus forming one black layer, while the other layer remained totally unaffected and as pure as the driven snow. So there was a little discovery – a treatment that can be applied to no other stone – that instantly raised the plebeian agate to the ranks of a gem.

Even today, when cameos are no longer so fashionable as formerly, they are in high repute as works of art, and many wonderful collections – certain single pieces valued as high as $10,000 and more – are in private hands as well as in museums. Carnelian and sardonyx are not natural gems but are likewise created by dyeing the bluish-gray agate in different solutions. The black stone commonly called onyx really should not be so called, but should have a name of its own; for onyx, properly speaking, means a stone of two layers of different colors, whereas what is commonly asked for as onyx – in especial demand by those in mourning – is in one layer only. However it would be practically impossible to change this popular misconception.

One of the most beautiful natural agates I have ever seen – and I paid its weight in gold for it – is a bit about two and one-half inches long and one and one-half inches wide. In it Nature, for once a Christian has formed a lovely Madonna – no doubt about its being a Madonna. As clear, as exquisitely colored – soft reds and blues on a gray ground – as droopingly tender as an Italian Primitive, it glows in the cloudy agate, miniature features delicately marked tiny prayerful hands, a robe beautifully fashioned – a miracle to make one believe in divine intervention. How we ask, could an accident be so perfect even to the sacred droop of the head?

Editor’s Note – This is the first of several articles by Doctor Kunz and Mrs. Ray. The next will appear in the issue for December tenth.

To read Part 2 of this article, click here

For further information on George F. Kunz at Palagems.com, see also:

- California Gem Mining: Chronicle of a comeback by David Federman

- On Kunz & Kunzite by Lawrence H. Conklin