Rarer Gems

The Rarer Gems

By George A. Bruce, International Import Company

Atlanta, Georgia

The text that follows was published in two installments in the December 1957 and January 1958 editions of Lapidary Journal. Most of the photographs are by Mia Dixon, Pala International's resident photographer.

Perhaps the most fascinating study in the field of gemology is that of the rarer gems. As with the stones themselves, there is a glaring scarcity of information concerning them and this article can by no means accomplish more than a few revolutions of a lap on a dopped stone in this regard. However, if it can serve as an impetus for others to cover more fully this highly interesting subject, it will have fulfilled its purpose.

Since language is a complexity of semantics, there justly is a wide variance of opinion as to the meanings of words. What, precisely does one mean when he denotes something as rare? If so-and-so is rare, then why not some other thing, etc? These are fair questions; for, manifestly, it is impossible to talk about or write on any subject with any degree of common understanding unless that subject first be defined. Therefore, rarity, in this article, is taken to mean the lack of the known abundance of materials suitable for cutting gemstones, particularly faceted ones.

The term known is used, for who is to say that in the future some sizable discovery of one or more of these minerals will not be made? All too often such concepts have been either ignored or taken for granted. This is unwise and we may take the example of [how] the famed amethyst jewelry of Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, was valued highly in her day; for there was no known abundance of it. Today it is much more common, yet it has lost nothing in beauty, but the value of that jewelry is now only a fraction of what it was in her time, vastly inflated prices notwithstanding. This, then, is not so facetious a point as it may at first appear.

Then we are confronted with the fact that the finest or largest extant specimen of even common material is rare, since there is only one of it in the world. This is true; for without regard to what may be the finest amethyst (to use that gem as an example again) very high-grade amethyst can be costly. It is a fact that this material has brought $15.00 per carat wholesale in New York this year, yet to many hobbyists this would seem preposterous. It is simply that it never appears on the hobbyist's market, hence he is innocently ignorant that it exists at all.

Example after example could be cited as to what is rare, so we must necessarily limit the scope of this article to those gems whose species is scarce and not consider the uniqueness of the best or the largest specimen of each gem material. Occasionally we will find that some variety is rare while its species is not. Such examples would be the alexandrite which is a chrysoberyl, a not uncommon material, and the padparadscha, an orange or aurora-red sapphire, a second material which is reasonably bountiful. These and others will be discussed.

A third point to be eliminated is the rare and unusual colors occasionally encountered in common substances, or the infrequent flawlessness of a gem popularly said to be always flawed. In the first instance we have such examples as fancy-colored diamonds (red, blue, green, etc.), vivid red zircons of great brilliance, star rubies and star sapphires exhibiting 12 rays rather than 6, topazes in the finer madeira and pink tints, etc. However, none of these substances per se are rare but quite the contrary, and so they are eliminated by definition and with this explanation. Inclusion of the chrysoberyl, alexandrite, and the sapphire padparadscha, is excused on the ground that the variety, or sub-class, is known by a name totally devoid of reference to its species. Regarding flawless gems usually accepted as always flawed, the emerald represents the best example. A perfect one is, of course, rare in the common sense of the word, but emeralds, as such, are not of uncommon occurrence despite their costliness.

Again, there are those stones so rare that they are true oddities of nature. There are so few that often the best authorities must profess ignorance of their existence and no reference to them is made even in the most comprehensive text on the subject. Although absolutely rare they are better called "brag" stones. They never appear on the market and it is quite impossible for any, save a few fortunate collectors, ever to acquire any. Such a gem is dickinsonite. A friend of the author has a specimen; it will weigh no more than a carat, if that. The existence of only two stones can be positively stated, but that a few more may exist is most probable. However, that such gems as these would ever be advertised is doubtful in the extreme and to compile a mere list of them would be an impossible task. Their omission, then, is solely due to these reasons.

Lastly, no description of tektites, particularly the rare and fabled billitonite (also known as agni mani and "fire pearl"), will be given as there is at present much argument as to what they really are, etc. and the theories pertaining to these are diverse and in disagreement. To describe their nature would be to predicate as true some facts which have not yet been proved conclusively. However, many varieties are rare and the interested reader would do well to investigate this highly interesting subject through the various texts and articles covering them.

The factors governing the price of rare stones are somewhat different from those which determine the price of popular ones. The latter are controlled in part by the dictates of fashion, demand, hardness, birthstone charts, etc. as well as flawlessness, depth of color, size, etc., while the former involves intermittent supply, the superstitions of the natives in foreign lands as well, etc. For example, the alexandrite is highly prized in the Orient and, since the supply is small and the demand great, there is no necessity for them to export the gems unless the price paid definitely warrants it.

The kyanite is another gem highly prized in India. This stone is a good example to use in showing that the utter flawlessness of rare gems may be in part disregarded, for kyanite nearly always has visible inclusions of hematite. Since the Indians cut for maximum weight in preference to maximum clarity, we may expect kyanites to contain inclusions. In purchasing one, color is far more important than flawlessness; for one may search all his life without ever finding a specimen free of these inclusions. Kyanites of good color are difficult enough to obtain; to ask more is often next to impossible.

The main controlling factor on price, however, is the rarity itself, particularly for a quality stone of good size. Prices may often exceed those of some of the precious stones. On the other hand, small gems are available from time to time and can meet the budget of the small collector. Small, faceted alexandrites, for example, can be had for $5.00 per stone, but these are not high-grade gems and when another is priced at between $100.00 and $200.00 per carat, it is not to say that this gem is not a bargain. It need not be ten or twenty times better than the $5.00 stone to cost many times as much; for it may be fifty times more rare in some quality than the less expensive one for its respective quality.

The mysteries of nature, deep in the bowels of our Earth, are exhibited in various degrees in all gemstones and the fascination, lore and romance which accompanies them is legend, but the rarer gems abound in even greater mystery. The search for them often involves adventures never to be forgotten and rivaling the most imaginative fiction ever written.

Few collectors ever satiate their desire in adding the unusual to what may already be a representative assortment of gemstones; for each jewel is an individual entity distinct from every other one. Each, in Keats' words, is "a thing of beauty" and "a joy forever." But for all their beauty, they are both educational and practical. They give us firsthand knowledge of many of nature's secrets and the means of adding attractiveness to our attire should we decide to use them in jewelry. By and large, they enhance in intrinsic value as well and have through the ages been recognized as excellent investments and easily portable wealth in times of distress. Their ratio of value between nations is almost constant; whereas, currencies fluctuate greatly. This is highly applicable to rare gems as well as common ones; for as long as man shall inherit the Earth, he shall also seek the rare and unusual to satisfy his desire for distinctiveness.

Before going into a discussion of the stones themselves, the author would like to take this opportunity to invite any interested readers to correspond with him in regard to rare gems. Further, any information tendered regarding new "finds," species, etc. would be most welcome.

Brazilian alexandrite (daylight at left; incandescent at right), emerald cut, 3.18 ct, 9.06 x 7.23 x 5.1 mm. This stone has been sold.

Alexandrite

One of the most interesting gems, and certainly the most sensational, is the alexandrite. The very time and place of its discovery alone almost defies credulity.

In the wilds of the Ural Mountains, approximately 57 miles east of Ekaterinburg (then Russia, now U.S.S.R.), on the right bank of a small stream called Takovaya, this gem was first found. Emeralds and other minerals had been mined there for years. Yet only on the very day of the coming of age of the Czarevitch Alexander Nicolajevitch, thereafter known as Czar Alexander II, in 1830, did this extraordinary stone add itself to the host of known gems. It appears only natural, then, that this variety of chrysoberyl would take its name from that ruler.

This would seem quite enough in itself to make an interesting story, but the alexandrite seemed destined to engage fully in the festivities accompanying the Czar's birthday; for in sunlight it is green, but under artificial illumination, it is red,—the national military colors of Russia! It is no wonder that the stone is so highly prized in that country. But its popularity is world-wide and it enjoys a great demand in America.

It was considerably later before this mineral was found in other locales, again in Russia. This time it was uncovered in the Southern Urals by the Sanarka River. In the first instance, it was discovered accidentally in mica-schist near a strata of granite; whereas, the second location consisted of auriferous sands. Usually it shows three crystals trilled together, but twin or single crystals are sometimes found, though rarely.

These Ural stones quite frequently exhibit a very deep raspberry red, and are preferable to the Ceylon stones which were found years later in the seemingly inexhaustible gem gravels of that island. Also, the green (the true color of the alexandrite) of the Ural stones generally surpasses in beauty the green of the Ceylon gems. A number of large gems have been mined in Ceylon, some exceeding 60 carats. Such large specimens are far from commonplace but the vast majority do exceed 4 carats in the rough. In some instances, the Ceylon alexandrites show chatoyancy when cut as a cabochon. These alexandrite cat's-eyes are as fine as their brother, the cymophane (the true chrysoberyl or oriental cat's-eye ), and display a well-defined "eye" as well as a change of color. The writer has one weighing 2.90 carats.

Quite recently, alexandrites and alexandrite cat's-eyes have ·been uncovered in Brazil, but usually the change of color is to a brownish-red and not nearly so attractive as the other two.

This change of color is due to pleochroism. It is highly trichoic, with a wide absorption gap between the green and red in the spectrum. The reason for the latter is that daylight contains a great deal of blue light which suppresses the red and enhances the green. In artificial light there is much infrared, such as tungsten filament, and the red is therefore enhanced and the green suppressed. Within this gap is that part of the spectrum to which the human eye is most sensitive. A deeply cut stone greatly enhances this effect.

All fine museum collections contain excellent examples of this rare gem. In the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C., a very fine stone is displayed from time to time that is said to be the largest in the World.

Its major characteristics are identical, of course to chrysoberyl since it is a variety of that mineral. Chemically it is beryllium aluminate BeAl2O4. Its hardness is 8½ (surpassed only by corundum and diamond); luster, vitreous; refractive indices, 1.745 and 1.754; specific gravity, 3.71; refraction, biaxial, positive; dispersion (B-G), 0.015; color, emerald green to olive green, Russian stones tending toward blue-green. In popularity and demand, it surpasses all rare gems and there is every indication that it will continue to reign supreme.

So frequently are the crystals cloudy and abundant with fissures that little faceting area remains. This factor further contributes to the costliness of fine Alexandrites.

Amblygonite

Two Greek words meaning "blunt" and "angle" give us the name for amblygonite. The brilliant and the modified brilliant are two cuts generally used in faceting this interesting gem.

Most faceting material comes from Brazil, but in the U. S. small deposits were found atop Mt. Plumbago in Newry, Me. in 1940–41. Large euhedral crystals were found there in pegmatite pockets about 200 yards east of the old Nevel pollucite quarry.

It is also found at Hebron, Me., in association with lepidolite, quartz, albite, apatite and tourmaline (red, green and black) in masses of granite. Eight miles away in Paris, Me., it is found at Mt. Mica together with tourmaline. However, Maine has no monopoly; for it occurs in Saxony at Arnsdorf and Chursdorf, again in granite and in association with tourmaline as well as garnet. It has also been uncovered at Montelras, Creuze, France and Arendal, Norway.

It comes in several hues, e.g. white (colorless), bluish, brownish, grayish, greenish and yellowish. The pastel shades of green, and particularly yellow, are those most often encountered in faceted stones.

It is a rather brittle substance with a hardness of 6; specific gravity, 3.01 to 3.09 and of a vitreous luster. The chemical formula is Al2F62 (R3PO4-Al2P2O8).

Analcite

Again the Greeks give us the name of another rare gem, analcite. It is a derivative of their word for "weak." The reference is to its weak electrical power when heated or rubbed. It is well known that the Greeks experimented with amber towards this end with excellent success.

Like the fabled arguments of the Greek philosophers, this mineral caused great debate concerning the correct class to which it really belonged. Men such as Brewster, Mallard, Ben Saude and Rinne conducted innumerable experiments regarding its optical properties.

It has been found on the Cyclopean Islands, off Catania, Sicily, the Fassathal in the Tyrol, Kilpatrick Hills, Scotland, Glen Farg, near Edinburg, in Ireland, Iceland, Bohemia, Norway, Greenland, Japan, etc. In the United States, it has been seen at Bergen Hill, N.J., Yonkers, N.Y., Perry, Me., Table Mountain near Golden, Colo., etc. Excellent specimens have been uncovered at Cape Blomidon, Cape d'Or, Five Islands, Martial's Cove and Swan's Creek, Nova Scotia.

It is usually colorless or white, but sometimes is grayish, greenish, reddish or yellowish. It is found transparent to opaque with a vitreous luster. The hardness is 5 to 5.5, specific gravity, 2.22-2.29, 2.278. Like amblygonite, it is brittle.

Anatase

Anatase was not the first name for this gem. It was first called octahedrite by De Saussure because it was usually found in octahedrons, then oisanite by Delametherie. Finally, Hauy gave it its present name from the Greek word, loosely translated as "extension". It is closely related to rutile and brookite.

It occurs most commonly in various shades of brown, but also deep blue and black. It appears a greenish-yellow by transmitted light.

Bourg d'Oisans produces this gem together with another rare material, axinite. It is also found in Bavaria, Norway, Ural Mountains, England and Brazil. In America, it occurs at the Dexter lime rock, Smithfield, R.I. and at Brindletown, N.C.

Some fine examples are among the displays of the leading museums and in private collections.

It is a brittle stone with a hardness of 5.5 to 6, of an adamantine luster, a specific gravity of 3.82 to 3.95 (lower than rutile) and refractive indices of 2.493 and 2.554, also lower than rutile. It is doubly refractive to a degree, 0.061 as compared to the extremely high 0.287 for rutile. The chemical composition is Ti O2, titanium dioxide.

1.79-carat natural Brazilian oval andalusite. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Andalusite

The rare gem andalusite most nearly competes with the alexandrite in displaying sensational phenomena. However, rather than changing color, it displays two colors at once. This marked pleochroism is more beautiful when exhibiting green and red, but quite attractive when showing green and yellow.

It is seldom found in as large a crystal as the alexandrite for faceting purposes, but faceted gems in excess of 20 carats are known. Large and even huge crystals are found, but are, unfortunately, opaque and unattractive in color.

When particularly fine, some andalusites have been sold for the more expensive alexandrite. On the other hand some types of tourmaline, when properly cut, so closely resemble andalusite that testing with a piezometer is advisable. Other tests are possible, but this is the most accurate.

As might be guessed, this lovely gem takes its name from the area of its first discovery, Andalusia, Spain. However, most of the present-day material comes from the Minas Novas district of Brazil,—the same district where Brazilian alexandrite is found. It is found there in gem gravels associated with blue and white topaz. Some specimens also come from the gem gravels of Ceylon.

In chemical composition it is identical to another rare gem, kyanite, having the formula Al2O3SiO2. To best show the red tint, since its true color, as with the alexandrite, is green, one must cut the table at right angles to the edge of the prism. Its hardness is 7½; luster, vitreous; specific gravity, 3.12 to 3.18.

This gorgeous gemstone is a 56.50-carat apatite from Brazil, and is now in the hands of a very happy collector who has an insatiable appreciation for the phenomenal. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul)

Apatite

Because of the myriad forms in which apatite is found, the Greek word for "deceit" was chosen as an apt name for this gem.

The yellow variety from Cerro Mercado, Durango, Mexico is not rare, but the other colors, when fine, definitely are.

The so-called asparagus stone, first found near Murcia, Spain, is the yellow-green variety. Moroxite is the blue or bluish-green apatite from Arendal, Norway. The sky-blue variety, sometimes called lasurapatite, occurs with lapis lazuli in Siberia along the, banks of the Sludianka River which empties into huge Lake Baikal where Genghis Khan held his Karkorums. Sky-blue apatite is also found in Australia, Ceylon and in Burma near Mogok (meaning "horizon"), fabled for beautiful pigeon-blood rubies and almost every other gem except diamond and emerald. A sea-green variety occurs in Ajmer (Rajputana) and Devada (Madras), India. Canada and Mt. Apatite, near Auburn, Me. have produced green crystals. Lilac or violet stones of lovely hue are associated with tin ores at Ehrenfriedersdorf, Saxony.

Sometimes apatite is fibrous and may produce cat's-eyes. The author has a fine green one weighing 9.12 carats, originally in the Phillips collection. These are much rarer than the faceted stones, however.

A number of superb specimens may be seen in museums and private collections, some of which are colorless, which should be the true color of apatite if it did not most frequently occur with various elements which render numerous tints to it.

Apatite is soft (5) and was the mineral chosen by Mohs for that number in his scale. The refractive indices range from 1.632 to 1.642 and from 1.634 to 1.646, the double refraction ranging from 0.002 to 0.004. It is of vitreous luster, occasionally even resinous. Chemically it is a calcium-fluorine phosphate with the formula Ca4(CaF) (P O4)3.

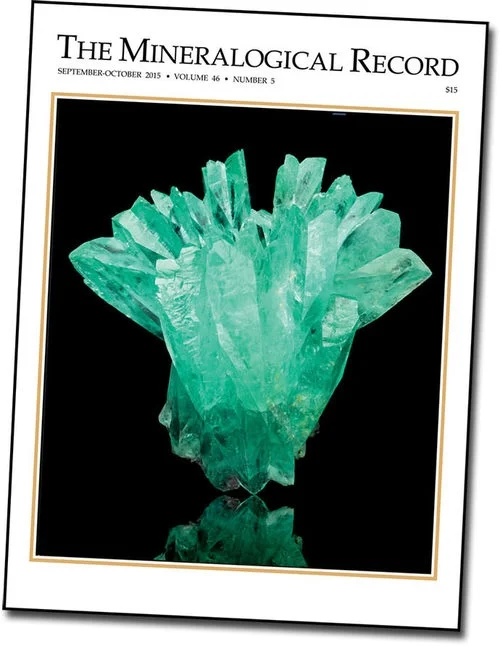

The Inca King was the cover star for the Sep–Oct, 2015 edition of Mineralogical Record. (Photo: Augustine de Valence, MIM)

Apophyllite

Apophyllite is a colorless to pink stone with a hardness of only 4½ to 5. Since under moderately high temperature, this mineral spreads, its name was taken from the Greek words for "off" and "leaf."

It seems to favor mountainous territory; for it is found in the Harz Mountains at Andreasberg, Germany and the Syhadree Mountains, Bombay, India.

The refractive indices are 1.535 and 1.537, the specific gravity ranges from 2.30 to 2.50 and the luster is pearly to vitreous. Its chemical composition is KF. Ca4Si8O12(OH)16. Hardness is 4½ to 5.

Axinite from Tanzania: 15.5 x 8.9 x 13.5 cm. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Axinite

Axinite may produce large crystals, but very seldom are there areas from which even a medium size gem may be cut. It is usually cut as a cabochon, although sometimes it is faceted.

It may be quite brilliant and when clear and of the preferred clove-brown color, it is a handsome gem. Sometimes it shows a violet tint which can be attractive, but the frequent gray color is undesirable.

The stone is brittle, of a vitreous luster, has a hardness of 6½ to 7 and a specific gravity of 3.29 to 3.30. The formula is HMg Ca2B Al2(SiO4)4.

Superb crystals occur at St. Christophe near Bourg d'Oisans, France in conjunction with albite, prehnite and quartz. It also is found in Silesia, the Tyrol, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, Italy, Hungary, Russia and England. In the United States, it occurs in Phippsburg and Wales, Me., Cold Spring, N.Y., Franklin Furnace, N.J., Bethlehem, Pa., Luning, Nev. and in San Diego and Madera Counties, Calif. It also occurs in the northern part of Baja California, Mexico.

Since the crystals frequently resemble an axe, its name was derived from the Greek word for "axe." As a cut gem it is exceedingly rare.

1.55 ct. fancy cut benitoite, Inventory #18850. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Benitoite

This beautiful gem received its name from San Benito County, California where it was first discovered in 1907. It so closely resembles the sapphire that it was sold as such for a considerable period of time until it proved to be an entirely new material. So far, it has not been found anywhere else.

It is not always blue; for clear areas may be evident in some of the larger stones. Then again, it may have a purple tint.

When one speaks of a large benitoite, one, nevertheless, speaks of a small to barely medium size gem; for few, indeed, exceed 1 carat after cutting. A flawless gem slightly over 7 carats is on record, another of 6¼ carats, etc., but these are outstanding.

The better museums have excellent specimens, but those in the hands of private collectors will equal them.

Benitoite is a barium-titanium silicate Ba TiSi3O9with a hardness of about 6½, refractive indices of l.757 and 1.804, specific gravity of 3.65 to 3.69 and a vitreous luster. In cutting, the table should be so oriented that the crystallographic axis is on the same plane with it.

The color of benitoite is very stable and usually very lovely. It is avidly sought by collectors and justly so."*

*(See The Story of Benitoite, The World's Rarest Gem in the February 1957 issue of the Lapidary Journal for the most complete account ever written of this un usual gem.)

Large rare cats eye 20.18 cts. beryllonite from Pakistan, Inventory #16118. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Beryllonite

Beryllonite is very rare and, obviously takes its name from beryllium of which it is a variety. It is, like benitoite, a substance found only in America. The locale is Stoneham, Maine where it occurs in conjunction with beryl and phenakite, both beryllium minerals.

Generally it is a colorless stone, but may occur with a slight yellow tint. The hardness is only 5, the specific gravity varying from 2.80 to 2.85, the refractive indices are 1.553 and 1.565. It is of a vitreous luster and has the chemical formula NaBePO4.

9.11 cts. brazilianite, Inventory #18523. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Brazilianite

Brazil, the country where the greenish-yellow brazilianite is found, gives it its name. Although there is, as yet, no abundance of material, that which is found generally is of good quality and provides faceting material. The color is usually weak, but nevertheless, attractive.

It corresponds to the formula Na AL3-(OH)4(PO4)2. It is only 5½ in hardness, has refractive indices of 1.598, 1.605 and 1.617. The specific gravity is 2.94. The luster is vitreous.

This is a relatively new discovery and much desired by collectors. The American Museum of Natural History in New York owns a 19 carat brilliant cut stone. A few other gems of commensurate size have been cut.*

*(See Brazilianite, an article about this gem in the December, 1948 issue of the Lapidary Journal.)

Brookite from Pakistan, 7.5 cm x 5.0 cm. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Brookite

The interesting gem brookite is related to anatase and rutile. It is softer than rutile and of the same hardness as anatase, namely 5½ to 6.

It was named after Harry James Brooke (1771–1857), an English crystallographer and mineralogist. Other varieties are jurinite, named for L. Jurin (1751–1819), a Swiss naturalist, and arkansite for Arkansas where black crystals are found at Magnet Cove in the Ozark Mountains.

Brookite is found with albite and quartz at Bourg d'Oisans primarily, but also in Switzerland and near Miask in the Ural Mountains. Small crystals are also found in America in North Carolina, Paris, Me. and Ellenville, N.Y.

The preferred color is yellow, but as has been mentioned, it is black when opaque. It is rarer than anatase and far more so than rutile. The luster is adamantine, the specific gravity, 3.87 to 4.01 and the refractive indices are 2.583 and 2.741.

Cassiterite. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Cassiterite

To find cassiterite clear enough for faceting is quite rare; for it is usually opaque. It is a tin ore and is the major source for that metal.

The word is derived from the Greek word for "tin" and since Cornwall, England was the main supplier for the Romans, this area was called the Cassiterides.

Faceted gems may be brown, yellow or colorless and are pleasing to see. The high specific gravity, 6.7 to 6.8 easily distinguishes it from gems of similar hue. The refractive indices are 1.997 and 2.093. This gives it a large birefringence, while its color-dispersion is great also, viz. 0.071 (B-G). The luster is adamantine; hardness, 6 to 7 and chemical formula Sn O2.

Golden Danburite from Tanzania, 51.29 carats. Danburite is a crystalline mineral similar to topaz. It has a Mohs hardness of 7 to 7.5, so it’s very wearable. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Danburite

The original locality, Danbury, Connecticut, is the place from which danburite takes its name. Other locales are Russell, N.Y. and on Piz Valatscha, the northern spur of Mount Skopi in eastern Switzerland. Crystals from this latter area were once sold for bementite, named after C. S. Bement of Philadelphia. Some fine specimens have been found in Madagascar, Bungo, Japan, and in Mogok, Burma.

Danburite is closely related to topaz and andalusite since it is a calcium borosilicate, with the formula CaB2(SiO4)2. It is hard enough to mount (7) but usually is lacking in color. The deepest tint of yellow, however, is attractive, but cannot vie with the richer hues of topaz. It also possesses the desired brilliance for a gemstone, the refractive indices being about 1.630 and 1.636. The specific gravity is very constant, 2.99 to 3.01. Although it is of vitreous luster, polishing greatly enhances its brilliance.

Several of the American museums have excellent specimens, but probably the finest cut gem is in the British Museum of Natural History. It was found at Mogok, Burma and is absolutely flawless and transparent. It weighs 138.61 carats, 31.8 x 29.6 mm. (15.2 mm. in depth) and is a rich wine-yellow color.

Datolite

Datolite is closely related to danburite. It is not found as a cut stone as often as danburite since it is not as brilliant as other colorless minerals such as corundum, topaz and quartz crystal. It is usually yellowish-green, and quite soft; only 5 on the Mohs scale.

The best of the faceted gems come from material found in Habachtal, Austria, but it also occurs in the Tyrol, Harz Mountains, New Jersey, Michigan, Massachusetts and in Cornwall.

Since the massive material is very granular and rather easily split, the name datolite was derived from the Greek word for "divide." Like danburite, it is a calcium borosilicate, Ca(B.OH)SiO4. Pure crystals are colorless. The hardness is 5 to 5¼. The refractive indices are 1.625 and 1.699. It is doubly refractive and the specific gravity is 2.90 to 3.00.

Russian Quintet. Demantoid garnets from the Kladovka mine in the Ural Mountains. These stunning stones were mined in 2004 but only recently cut by master Marty Key. The 2.57-carat round is the finest green of this material's production. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Demantoid Garnet

The demantoid garnet is a very beautiful gem which can almost vie with the emerald in color and the diamond (its name is from the Dutch word demant, meaning "diamond") in brilliance. It is one of the most desirable of the rare gems. These garnets almost invariably contain inclusions of exceedingly fine byssolite needles, popularly referred to as "horsetails."

It was discovered less than 100 years ago, in the eighteen-sixties, in the form of pebbles in the gold-washings of Nizhni-Tagilsk. Later it was uncovered in other gold-washings in the Bobrovka stream on the western slopes of the Ural Mountains. Shortly thereafter, it was found nearby in situ. For a while these were called Bobrovka garnets. Many of the first stones were cut as cabochons, but this gem is so lively that this practice was soon discontinued.

The brownish-green and yellowish-green stones contain iron, but no chromium. However, the fine emerald-green gems do contain this element and chromium is believed to be the element which gives the emerald its color. Many persons prefer the rich emerald-rich demantoids over all other jewels. Its drawback is its softness—6½. No. other garnet is this soft. It should be mentioned here that there is another green garnet, the uvarovite, with a hardness of 7½, but the crystals are always exceedingly small. This is also a Russian gem and was named after Count S. S. Uvarov who was once President of the St. Petersburg Academy, now Leningrad.

Demantoids are usually rather small, but gems exceeding 12 carats have been recorded. All the leading museums and collectors have fine examples. The writer has a number of fine demantoids.

Andradite, with a chemical formula Ca3Fe2(SiO4)2, is the family name of the type of garnet to which the demantoid belongs. Other andradites are the lovely topazolite (the name obviously having been derived from its topaz color) and melanite (from the Greek word for "black.")

The refractive index of demantoid is very high, viz. 1.888 to 1.889. The brilliant cut is most suitable for this gem since its color-dispersion is the highest of any gem, 0.057 (B-G). Its luster, as is obvious from its very name, is adamantine.

21.22 cts. deep chrome green diopside cabochon from Tanzania. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Diopside

Diopside is a gem of great beauty and clarity. It belongs to the pyroxene group and corresponds to the formula CaMg(SiO3)2 in which some of the magnesium is replaced by ferrous oxide.

The most beautiful gems are those cut from Tyrol material. These are the most transparent, of bottle-green color, and have the highest specific gravity, 3.2 to almost 3.3. This is due to the higher iron content. The name is from the Greek words meaning "double" and "appearance"—because of its double refraction. It is a variety of malacolite, from the Greek word malakos, meaning "soft", because it is softer than the minerals with which it is associated. As iron replaces the magnesium in larger proportions, it becomes hedenbergite (after Ludwig Hedenberg) with the formula CaFe(SiO3)2.

It is soft, 5 to 6. The refractive indices are 1.671 to 1.726. The specific gravity is 3.27 to 3.31, and the luster is vitreous. It is also found at DeKalb, N.Y. and elsewhere in the United States, Minas Gerais, Brazil, Ceylon, Madagascar, Kimberley, South Africa (in the blue-ground and containing chromium), and in fabulous Mogok, Burma. Fine white cat's eyes have been cut from material found in the Ala Valley, the original point of discovery.

Sometimes it is of a fibrous nature, such stones being found in Mogok (Upper Burma, about 90 miles north-east of Mandalay) and this chatoyant material, when cut as cabochons, often displays superb cat's-eyes or stars. They will rival the best green tourmaline cat's-eyes. (The author would like to interpolate the remark here that far more gem materials exhibit chatoyance than is commonly supposed and that a complete and detailed paper should be done regarding them).

Diopside is sometimes found in large crystals and a number of fine cut gems may be seen in the most noted museums. One weighing 11.30 carats is in the author's collection.

Dioptase from the Tsuemb Mine, Namibia measuring 12 x 8.5 x 2.5 cm. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Dioptase

Since the cleavage planes may be distinguished by looking through the crystal, Hauy derived the name, dioptase, from the Greek words for "through" and "to see."

Gems cut from this material are rare indeed as little cutting area is ever present, but the few cut stones extant are very beautiful; for they are a rich emerald-green in color. Like many stones such as the balas ruby (red spinel), etc. it is erroneously called copper emerald. This is due to its color and because it contains copper, the formula being H2CuSiO4. Since copper will generally give a deeper color to minerals than chromium, dioptase is usually a slightly darker green than the preferred emerald-green color, but the difference is not so great as to call its color dark green rather than emerald-green.

Its hardness is 5, much softer than emerald, but the specific gravity is higher, being 3.27 to 3.35. The refractive indices are 1.644 to 1.709 and the luster is vitreous.

The cut gems met with on the open market are usually small, but a few large crystals have been found in the original locale in the gold-washings in Transbaikalia, Siberia in the Kirghiz Steppes; others were found in Persia. Excellent specimens also occur in French Equatorial Africa and SouthWest Africa; Rezbanya, Rumania; Copiapo, Chile, and Cordoba, Argentina. Faceted gems are very beautiful and much desired by collectors.

Gem dumortierite from the Umba Valley in Tanzania, striking octagon cut, 7.8 x 6.26 x 5.5 mm, 2.14 carats.

Dumortierite

Dumortierite is very rare when found in the preferred blue or violet hues. It was named after Vincent Eugene Dumortier (1801–1876). It is even rare in polished slabs and certainly so in cabochons.

The formula is Al(AlO)7(BOH)(SiO4)3, the refractive indices are 1.678 and 1.689, the specific gravity is 3.26 to 3.36, the hardness, 7, and the luster, vitreous.

In the United States, it occurs at Harlem in New York City, at Clip in Yuma County, Arizona; Nevada and in California, where it is locally called "desert lapis." Foreign occurrences are in Norway, Madagascar, South-West Africa and near Lyons, France.

26.54 cts. olive green enstatite from Mogok, Burma. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Enstatite

Enstatite is a very interesting material, (Mg, Fe)SiO3, and when the percentage of iron increases, the substance technically becomes hypersthene. If pure, it would be colorless, but iron is invariably present and gives it its green tint.

However, the richer green stones from the blue-ground in South Africa contain chromium also. These have been called green garnets, but they are totally unrelated to garnets and the practice should be discontinued.

Since enstatite is refractive, the Greek word for "adversary," was chosen for its name, while the iron-rich hypersthene was chosen from the Greek for "very tough". Hypersthene is rarely cut since it is opaque. When containing small pieces of brookite it is cut into cabochons.

Bronzite is another variety of hypersthene with the low specific gravity of 3.2 to 3.3. It is a beautiful bronze color and of a metallic luster. Since it is sometimes fibrous it may be cut to show chatoyance. The writer recently owned a beautiful cat's-eye showing a golden "eye" on a rich bronze ground, weighing 40.46 carats. It is found in Styria, a province of Austria; India, and Mogok, Burma.

Other stones in this group are bastite or schiller-spar, very closely related to bronzite except in color and sheen (it is most often found in Harz) and diallage which is more closely related to hypersthene, most often found in the Western Alps, the Appennines and on Skye Island.

Most of the varieties are now called simply enstatite or enstatite-hypersthene. Enstatite has a hardness of 5.5, is of a pearly to vitreous luster, has a specific gravity of 3.26 to 3.30 and refractive indices of 1.656 to 1.665 for the brown material and 1.665 to 1.674 for the green. In addition to green and brown, it may also occur in white, yellow and gray.

In addition to the above-mentioned locales, beautiful hypersthene has been found on the coast of Labrador and St. Paul Island and some material comes from Mogok in Burma. This material is often called Labrador hornblende. In the United States, recoveries have been made at the old Tilly Foster magnetite mine, New York, (Brewster and Putnam Counties), Edwards, N.Y. and in Texas and Pennsylvania. A number of excellent cut gems are in museum displays.

Epidote from Haramosh Peak, Gilgit Agency, Pakistan, 8 x 5 x 1 cm. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Epidote

The unique color of the pistachio-nut is present only in epidote. Hauy chose the Greek word meaning "added" for the name of this mineral. Other closely related stones are zoisite, named after Baron von Zois, piedmontite, from the original locale, allanite after Thomas Allan (1777–1833), and orthite from the Greek word for "straight." Epidotes of preferred color have been called pistacites. This gem may be very lovely and is a proud addition to any collection of colored stones since this color is totally unobtainable in any other jewel.

The chemical composition is expressed in the formula Ca2Al2 (AlOH)(SiO4)3, the refractive indices are 1.716 to 1.768, the luster is vitreous to metallic, the specific gravity is 3.4 (3.5 for piedmontite and 4.2 for allanite) and the hardness is 6½.

Piedmontite, as the name implies, is found in San Marcello (manganese mines) in the Piedmontese Alps. Occasionally, beautiful crystals of a cherryred color are found and are cut into fine gems.

The lovely pistachio-colored crystals once came exclusively from Knappenwald, Salzburg, Austria. Other yellow-green and brown stones have been uncovered in Arendal, Norway; Prince of Wales Island, Alaska; Kenya, South Africa; and Brazil. In the United States, stones very similar to the Austrian gems have been discovered in Rabun Gap, Georgia (not far from Atlanta). Green ones occur in Roseville, N.J. and Haddam, Conn.

Pale yellow 7.89 cts. oval euclase. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Euclase

Euclase is an exceedingly rare and attractive gem. It was first uncovered in Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais, Brazil in association with topaz in veins of quartz. It is also found in the Sanarka River gold-washings in the Ural Mountains, Kashmir, India, and Tanganyika, South Africa.

It comes in several colors, the principal ones of which are blue and a sea-green, not unlike aquamarine. It has excellent cleavage, hence the Greek term for "good cleavage" was selected to name it.

Be(AlOH)SiO4 is the chemical formula. If pure, it would be colorless, as would many minerals, but certain impurities are evident and act as coloring agents. It is of a vitreous luster, 7½ in hardness, has a specific gravity of 3.10 and the refractive indices are from 1.651 to 1.677.

Noted museums own choice specimens as do a number of private collectors. The author recently saw a splendid collection owned by a New York dealer and was informed that it would only be disposed of in toto. This is admirable and as it should be.

Sharp cat's eye fibrolite (sillimanite), 63.15 carats, 22.71 x 22.40 x 13.93 mm. Every light creates an eye; notice the thin white eye in the middle and the thick mauve bands outside. (Photo: Jason Stephenson)

Fibrolite

The first specimens of fibrolite were all quite fibrous, hence its name. It is alternately known as sillimanite after Benjamin Silliman (1779–1864) and is coming to the fore in the category of rare gems. Silliman was an early distinguished Professor of Mineralogy at Yale University. A great deal of work has been and is being done on this stone.

Fibrolite and andalusite are chemically identical with the formula Al2SiO5. Usually, it is unsuitable for faceting as is the case with most rare gems, but occasionally it is a pale sapphire-blue resembling iolite. Massive forms are often mistaken for grayish-brown and grayish-green jade.

Like iolite, it can appear blue when viewed in one direction and of a yellowish hue in another. The specific gravity is 3.25, the hardness 7½ in crystals and 6 to 7 in the massive material. The luster is vitreous and the refractive indices are 1.658 to 1.677. When pale in color, it more closely resembles euclase, but the latter has a specific gravity of only 3.10.

It first came to light in the ruby mines at Mogok, Burma where it was found as crystals and water-worn pebbles. It is also found in the gem gravels of Ceylon.

Since it is fibrous, cat's-eyes are met with from time to time and the "eyes" almost rival those of the cymophane (chrysoberyl). These cat's-eyes and the faceted gems are in constant demand and the supply is small. One may consider himself very fortunate to list a good fibrolite in his collection. Fibrolite from a recent find in Idaho is sometimes marketed as "gem sillimanite" but, while the material is an interesting and fairly rare cutting material, it bears little resemblance to good fibrolite.

Hambergite from Pakistan, 4 cm in height x 7 cm in width x 2 cm in depth. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Hambergite

Beryllium minerals give us many handsome gems and hambergite is still another. It was named for the Swedish mineralogist, Axel Hamberg (1863–1933.) Although it is now found in Madagascar, it was for years obtainable only from southern Norway.

The faceted specimens are Madagascar material. Some small crystals, clear enough to be faceted in some instances, were recently discovered at the Little Three Mine near Ramona, San Diego County, Calif. by Captain John Sinkankas, U.S.N., author of the book Gem Cutting—A Lapidary Manual.

The formula is Be2(OH)BO3, the refractive indices are 1.553 to 1.631. The birefringence is 0.072, which is greater than that of all other gems with the exception of sphene and cassiterite. On the other hand, only the opal among gems has a lower specific gravity; for the specific gravity of hambergite is 2.35.

The hardness is 7½, a little more than quartz crystal which, in the cut stone, it closely resembles. It has a vitreous luster. Cut specimens are extremely rare.

Idocrase

Since idocrase appears on Mount Vesuvius, it is alternately known as vesuvianite. For years these gems were cut in Naples, Italy.

The compact masses are not rare, but clear pieces certainly are. They afford a wide range of color: yellow, blue, red and colorless, but in the majority, they are either green or brown. These are usually step cut.

Californite is the massive variety. Several years ago this was offered as jade, or "California jade", but it should not be confused with genuine jade, which has since been discovered at several California locations. Beautiful yellow-brown stones found near Laurel, Quebec, Canada were once sold as "laurelite" in an attempt to popularize this variety. Xanthite, the name derived from the Greek word for "yellow," is found in Amity, N.Y. Cyprine was named for the island of Cyprus (this island was the source of copper for the ancients) because of its sky-blue and greenish-blue color, but it is found in Tellemarkin, Norway.

Idocrase resembles, in crystalline form, several other minerals, hence the Greek words for "form" and "mixing" were selected for its name.

It is a complex substance which corresponds to the chemical formula Ca6Al(AlOH)(SiO4)5. The refractive indices are 1.700 to 1.721, the specific gravity is 3.35 to 3.45, the hardness, 6½, and the luster is vitreous.

The green and brown crystals are found in the Ala Valley and on Mount Vesuvius, Italy; Zermatt, Switzerland; Zillertal and Pfitschtal in the Tyrol, and close to Lake Baikal in Siberia. The Laurentian Mountains in Eastern Canada produce the golden-brown variety. The best californite occurs in Siskiyou County but it is also found in twelve other counties of California. A substance closely resembling this material has been known in Switzerland for many years.

Iolite cubes showing the gem's dichroic properties. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Iolite

Iolite or cordierite is a particularly fascinating gem. Its sapphire-blue color is most pleasing and when viewed from the opposite direction, its yellowish hue is remarkable. This hue often has tints of brown or gray. Other names for this stone are dichroite (since it is highly dichroitic), water-sapphire (which is the pale blue color) and lynx-sapphire (the dark blue color). Some material from India, Norway, etc., contains spangles of hematite, thus producing a type of sunstone. Iolite may at times appear violet, hence the name iolite from the Greek for "violet." Cordierite is named after Pierre Louis Antoine Cordier (1777–1861).

The difference between water-sapphire (light color) and lynx-sapphire (deep color) is achieved solely through cutting in one direction or another. If cut in a completely reverse manner, the stone will appear brownish when viewed from the top. The author possesses a number of stones displaying the various hues. The blue color is achieved by placing the table facet at right angles to the prism-edge.

Chemically, iolite is represented by the formula (Mg, Fe)4Al8(OH)2(Si2O7)5. The refractive indices are 1.532 to 1.549, the luster is vitreous, the specific gravity, 2.58 to 2.60 and the hardness, 7 to 7¼.

It is often cut cabochon and occasionally one will display asterism. These closely resemble star sapphires. The author recently had such a gem weighing 15.38 carats, 15 mm. round. When viewed from the top it was blue with a distinct six-rayed star, but by transmitted light it took on a violet tint. From the side, it appeared a dull yellowish-brown. This is another gem eagerly sought by collectors and museums and many possess fine examples.

The best stones are cut from rough material found in Ceylon, but Madras, India, Burma, Brazil and Madagascar also produce this gem. A number of fine stones have been discovered in Haddam, Conn.

1.49 cts. Kornerupine from Burma. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Kornerupine

The rare and lovely gem kornerupine was first discovered in Greenland and was given its name in honor of Kornerup. Later it was found in Madagascar. The Greenland material is usually yellow or brown, but that from Madagascar ranges from a sea-green to an almost emerald-green. Vivid green stones have also been recovered from the open pits in Ceylon. A little material has also been discovered in Saxony.

A fine green kornerupine is a decided asset to any comprehensive collection. A number of private collectors have excellent specimens, as do a number of the leading museums.

Kornerupine is doubly refractive and the refractive indices are 1.665 and 1.678 for the Madagascar stones and 1.669 and 1.682 for the others. The specific gravity ranges from 3.28 to 3.34, the hardness is 6½ and the luster is vitreous. It corresponds to the chemical formula MgAl2SiO6.

3.52 cts. unusually deep blue kyanite from Nepal. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Kyanite

Kyanite has also been called cyanite. It is a very beautiful sapphire-blue to colorless gem which has several peculiarities, one of which is that in certain directions its hardness is only 5, yet in other directions it is 7. This makes cutting extremely difficult. There is no other mineral which displays such a wide variety of hardness. A second peculiarity is that, chemically, it is the same as fibrolite and andalusite with the formula Al2SiO5. As the name implies, it is from the Greek word for "blue." Sometimes it is called disthene from the Greek words for "double" and "strength," referring to its variance in hardness within the same crystal.

The usual cutting is confined to the step cut when faceted, but cabochons are popular also. These often display "eyes" and may be as sharp as most other cat's-eyes.

Much of the material comes from India where it is found associated with sapphires in the Kashmir and also in Patiala and Punjab, India. Other locales are Switzerland, Kenya and Brazil. In the United States, Montana (a source of sapphires also) has produced some crystals and others have been found atop Yellow Mountain, near Bakersville, N.C.

The refractive indices are 1. 712 and 1.728, the hardness in one direction is 4 to 5 and in another, 6 to 7, the luster is pearly to vitreous and the specific gravity varies from 3.65 to 3.69.

Pear-shaped 5.65-carat natural padparadscha sapphire from Malawi, 12.08 x 9.80 x 6.34 mm with AGL certificate. Photo: Mia Dixon

Padparadscha

Padparadscha is a corruption of the Sinhalese (the natives of Ceylon) padmaragaya, meaning "lotus-color." It is an orange to aurora-red sapphire found in Ceylon and is exceedingly rare and beautiful.

Since information on sapphires (corundum) is easily obtained, suffice it to say that the chemical composition is Al2O3, the hardness is 9 (second only to diamond), the specific gravity is 4.00, the refractive indices are 1.761 and 1.769 and the luster is vitreous.

Dark red beauties: Painite, with a hardness of 8 on the Mohs’ scale, has been quite elusive, with only three known specimens collected between 1954 and 2000. Faceted painites are even rarer; the above stones are amongst the very few painites considered to be clear enough for cutting. Weight (l-r): 0.72 cts, 1.32 cts, 0.32 cts. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul)

Painite

The most recently discovered rare gem is painite, named for the British mineralogist, Mr. A. C. D. Pain, who is now working in Burma. The discovery was made in 1952 in a ruby mine near Mogok, Burma. The rough crystal weighed 1.70 grams and was a deep garnet-red in color. This is the only known specimen.

It was first tested by the London Chamber of Commerce Laboratory and then by the British Museum Department of Mineralogy. Mr. Pain later donated this crystal to the British Museum (Natural History). In testing, its weight was reduced to 1.48 grams.

It has a hardness of about 8 and a specific gravity of 4.00 to 4.02. The refractive indices are 1.7875 and 1.8159 and the luster is vitreous.

The British Museum has recently published an enlightening booklet concerning this material entitled, Painite, A New Mineral From Mogok, Burma, by G. F. Claringbull, Max H. Hey and C. J. Payne.

Brilliantly cut colorless 2.32 cts. phenakite. (Photo by Mia Dixon)

Phenakite

Phenakite was first encountered in association with emerald and alexandrite, embedded in mica-schist at Takovaya, Ekaterinburg in the Ural Mountains. Later it was also found in the Urals on Lake Ilmen at Miask. Other locales are Santa Barbara, Minas Gerais, Brazil; in the Kiswaiti Mountains, Tanganyika; Canton Valais, Switzerland, and in Colorado, U.S.A.

It is found in several hues, yellow, brown and red as well as colorless. Like many other gemstones, it is a beryllium mineral with the formula Be2SiO4. When colorless, it resembles quartz crystal, hence the Greek word for "cheat" was chosen to name it.

It is fairly hard, 7½ to 8 on the Mohs scale, but it lacks brilliance. The refractive indices are 1.654 and 1.670, the specific gravity is 2.95 to 2.97 and the luster is vitreous.

Rare 3.35 cts. pollucite from Connecticut, U.S.A. cut and faceted by Glenn Vargas, Inventory #21785. (Photo by Mia Dixon)

Pollucite

The rare gem, pollucite, is found in Maine, U.S.A. in association with hambergite. Its original name was pollux because it was found with a rare lithium mineral which was named after the mythological Greek character Castor, who was Pollux's twin. This first non-gem material was found at Elba.

The hardness is 6½, the specific gravity ranges between 2.90 to 2.94 and the refractive indices are 1.517 for the Elba stones and 1.525 for the Maine ones. It is of a vitreous luster.

Prehnite and tanzanite from Tanzania, 5.5 x 4 x 4 cm. (Photo by Mia Dixon)

Prehnite

Prehnite is a rich oil-green gem of considerable rarity in faceted stones. It was first discovered by Colonel Prehn at the Cape of Good Hope in the late eighteenth century. Good examples have also been found at Bougr d'Oisans, France; China, and at Bergen Hill and Paterson, N.J.

Two other gems very similar in character are chlorastrolite and zonochlorite. The former is found on Isle Royale, Lake Superior, Michigan. They make handsome and unusual gems, some even displaying a cat's-eye effect. The latter are found at Neepigon Bay, Lake Superior, Canada. They show alternate layers of light and dark green.

Prehnite has a hardness of 6, a specific gravity varying from 2.80 to 2.95 and is of a vitreous luster. The refractive indices are 1.615 and 1.645 and the chemical formula is H2Ca2Al2(SiO4)3.

16.27-carat oval brilliant South African rhodochrosite, 20.21 x 13.41 mm. From Ron Gladnick's collection. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Rhodochrosite

Although rhodochrosite would generally be considered an ornamental stone, upon occasion it is found in faceting grade. The rose-colored hue (from the Greek word for that color) is lovely indeed. It has also been known as dialogite from the Greek word meaning "doubt".

It is found in association with such metals as copper, lead and silver at Capnik, Hungary; Freiberg in Saxony; San Luis, Argentina, and Leadville, Colo.

It is quite soft, only 4 on the Mohs scale, and it has a specific gravity of about 3.70, increasing in direct proportion to the increase of iron. The refractive indices vary from 1.597 to 1.826.

The luster is vitreous and the chemical formula is M2CO3.

Rutile from Tetikanana, Ambatofinandrahana, Madagascar, 7.1 x 4.5 x1.5 cm. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Rutile

Rutile is more brilliant than a diamond, with refractive indices of 2.616 and 2.903 with a gigantic double refraction of 0.287. It ranges in color from a vivid red through brown and black. It has been mistaken for a black diamond from time to time because of its extreme brilliance.

We have already noted its close relation to both anatase and brookite. The rough crystals resemble cassiterite, but it is not related to that mineral.

The name rutile implies a red color, and the Latin word rutilus, meaning "red," was selected to name it.

Its chemical formula is TiO2, the luster adamantine, the hardness from 6 to 6½ and the specific gravity, 3.82 to 3.95.

Prominent localities are at Arendal and Kragero, Norway; Horrsjoberg, Sweden; the Tyrol, the Ural Mountains and Canada. In the United States, it has been found in small amounts at Warren, Me.; Lime and Hanover, N.H.; Waterbury, Bristol, Dummerston and Putney, Vt.; North Guilford and Monroe, Ct.; Edenville, N.Y.; Sadsbury, Pa.; Newton, N.J.; Stony Point, N.C.; Magnet Cave, Ark.; Grave's Mountain and in Habersham County, Ga.

Although fairly widely found the best material comes from Brazil and from a hiddenite deposit in Alexander County, N.C.

Among all the rare gems, only rutile and the padparadscha have been synthesized, the latter for its odd color and the former for its colossal brilliance or "fire".

Purple scapolite, 15.26 carats, about 17.3 mm. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Scapolite

Although scapolite has been known since about 1800 its discovery at the ruby mines of Mogok, Burma was recorded about 1913. The first gems were pink in color and thought to be pink moonstones until tests proved otherwise. Later, gems of white, yellow and violet-blue were found. Then, about 1920, scapolite was found in Madagascar and, in 1930, in Brazil. Some material has been found in Canada. The Madagascar gems are yellowish, but some of those from Brazil are almost golden.

Some of the ordinary Far East material has been dyed with organic dyes, probably logwood, to simulate black or purple cat's-eyes. Within the past year, a dealer offered some of these to the author as "black sapphire cat's-eyes" at a very exorbitant price. Everyone should examine black cat's-eyes carefully prior to making any purchase. The difference in hardness is, of course, very great. The author has a number of shell, or mother-of-pearl, cat's-eyes which have been dyed various and lovely hues, and black. These, too, may be mistaken for more valuable eyes by an undiscerning collector. These actually exhibit chatoyance and are not to be confused with the operculum (Latin for "lid", the door of the shell of a gastropod), for the operculum does not show any chatoyance.

The Burmese stones, upon occasion, display the cat's-eye effect. At first it was believed that only the pink and violet-blue ones possessed this property, but white and yellow scapolite cat's-eyes exist also. Cat's-eyes are primarily a man's stone, though not exclusively, but the delicate tint of the pink scapolite cat's-eye is well-suited to the most feminine wearer. Very strong white "eyes", rivaling the cymophane, are obtainable.

The name scapolite comes from the Greek word for "rod," which is the true shape of the crystals. Actually, there are two constituents, marialite (after Maria, Mary, from its pure white color) and Meionite, from the Greek word for "less". The formula for the former is Na4Cl(Al3Si9O24) and for the latter it is Ca6(SO4CO3) (Al6Si6O24). The luster is very vitreous, the specific gravity varies between 2.57 to 2.74 and the hardness is 6, though sometimes as low as 5. The refractive indices vary with color, but range from 1.544 to 2.68. The stones may assume large proportions.

Bright and open golden colored 94.41 cts.(!) sheelite from China; a nice collectors piece, Inventory #23737. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Scheelite

Scheelite occasionally affords us clear areas from which attractive faceted gems may be cut in various hues of white, yellow, brown, green, red and rare orange-yellow.

It is a brittle substance with a hardness ranging between 4½ and 5. The specific gravity is 5.90 to 6.10 and the luster is vitreous to adamantine. The refractive indices are 1.918 and 1.935.

It occurs in Bohemia, Saxony, the Tyrol, Salzburg, Hungary, Hnland, Chile, New Zealand, Tasmania and South West Africa. In the United States, it has been found in Monroe and Huntington, Ct.; Chesterfield, Mass.; Cabarrus County, N.C.; Nevada, California, Arizona and Colorado.

Golden sinhalite from Sri Lanka, 14.36 x 11.64 x 7.93 mm. Inventory #20073. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Sinhalite

For years the gem, sinhalite (from the word "sinhalese", the natives of Ceylon), has been sold for golden or brown peridot or olivine. However, Dr. G. T. Claringbull and Dr. M. H. Hey have proved conclusively that it is an entirely different mineral, with the chemical formula MgAlBO4.

The gem is quite attractive and often may show a tint of green in the yellower stones. Large gems may occur and still be free from flaws; the writer possessing one weighing 29.63 carats.

The hardness is between 6 and 7, the specific gravity about 3.34, the luster is vitreous and the refractive indices range between 1,659 and 1,696. The only known source is Ceylon. It is reasonable to assume that this gem may occur in Burma also.

Greenish-yellow with an orange corner, cut in France with lots of sparks. A fun "funky" stone. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Sphalerite

Sphalerite, also called blende, is found in large, clear crystals and is very unusual in that its refractive indices vary from 2.368 to 2.371 (near that of diamond) and its color dispersion, 0.156 for the B-G interval is over three times as great as the diamond. It is impossible to glance cursorily at this gem; one sees so many colors and combinations of colors that the effect is almost hypnotic. Unfortunately, it is quite soft, 3½ to 4, and is, therefore, unsuitable for wear.

The Greek word "deceitful" was selected to name it and an apt name it is. Its alternate name, blende, comes from the German word hienden for "deceive".

It is zinc sulphide with the formula ZnS. It would be colorless if pure, but is usually a yellowish-brown, and many colors may be observed due to its gigantic dispersion. However, both white and red sphalerite is found.

The specific gravity is 4.08 to 4.10 and the luster, adamantine to resinous. Some sphalerite exhibits the interesting phenomenon of triboluminescence, i.e. the ability to glow when heated by friction.

Sphalerite of gem quality is very rare; such occurrences primarily being in Sonora, Mexico and Picos de Europa, Spain.

Golden brown sphene. This stone weighs 40.33 carats and measures 20.03 x 20.05 x 12.86 mm. Inventory #18755. (Photo: Jason Stephenson)

Sphene

Sphene is another beautiful gem with a high refraction, the indices ranging from 1.885 to 2.050, and great color-dispersion, 0.051 for the B-G interval.

The name sphene is from the Greek word for "wedge", the shape of the crystals. Its alternate name, titanite, is from the Greek mythological titans.

It is harder than sphalerite, being 5 to 5½ on the Mohs scale. Though soft, it is used in jewelry. The specific gravity is 3.52 to 3.54 and the luster is brilliant. It has been found in various hues of yellow, brown, green, and red. Titanite is usually black or brown. The chemical formula is CaTiSiO5. Cut gems up to about 12 carats are known.

It occurs in gneisses and schists in the Alps, particularly Pfitschthal and Zillerthal in the Tyrol and also in the Swiss Alps, and in Madagascar. Fine specimens have been found in Pennsylvania, Maine and New York.

40.34 carat kunzite from the Ocean View mine. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Spodumene

Spodumene gives us two rare, valuable and beautiful gems, viz. the lilac-colored kunzite, named after the renowned gemologist, Dr. George Fredrick Kunz (1856–1932) and the green hiddenite named after its discoverer, William Earl Hidden (1853–1918). The name spodumene is from the Greek words for "burnt to ashes", which was the general appearance of the first crystals.

The discovery of hiddenite, much the rarer of the two gems, was made at Stony Point, Alexander County, N.C. in 1879. Crystals from this locality are the finest and are of an emerald-green. Others have been uncovered in Madagascar and Brazil, but these are of a yellowish-green tint. A few gems from Brazil are a lovely blue· color and were at first mistaken for lazulite. Spodumene may also be white or yellow.

The refractive indices are 1.654 and 1.669 for spodumene; 1.660 and 1.675 for kunzite and 1.662 and 1.676 for hiddenite. The luster is vitreous, the hardness is 7 and the specific gravity ranges from 3.17 to 3.23. The chemical formula is LiAl (SiO3)2.

Kunzite was first found at Pala, San Diego County, Calif. in 1903 and it is still being mined there. It has been found in all colors, from a light pink to a deep lilac-blue, the latter being much more infrequent. Other localities are Riverside County, Calif.; Branchville, Ct.; and in Maine.

Staurolite

Staurolite, also called lapis-crucifer, received its name from the Greek word for "cross", which is the natural shape of its crystals. The crystals are used in Basel, Switzerland as baptismal amulets.

It is usually a dark reddish-brown in color, but may occur in an almost madeira-topaz hue also. It is usually step-cut and closely resembles garnet. It is found at Monte Campione, Switzerland, on the Sanarka River in the Ural Mountains, and in the diamond-bearing sands of Salobro, Brazil. In 1898 it was found in fine crystals in association with rubies and rhodolite garnets in Mason's Branch, Macon County, N.C. A specimen containing an area of red faceting material, which must be one of the largest known such areas, was found in Upson County, Georgia by W. Frank Ingram, a friend of the writer.

The hardness is 7 to 7½, the luster is subvitreous to resinous, the refractive indices are 1.736 and 1.746 and the specific gravity varies from 3.65 to 3.75. The chemical formula is H Fe Al5Si2O13.

Fab four. From left, 8.50-carat purple pentagon from Sri Lanka (sold), 1.66-carat lavender trillion from Burma's Mogok Stone Tract (#7805), 2.35-carat brown oval from Sri Lanka (sold), and 4.28-carat mauve oval from Sri Lanka (sold). (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Taaffeite

In 1945, Count Taaffe, for whom taaffeite was named, discovered this gem in a most unusual manner. He had purchased a parcel of faceted spinels and, in examining them, he observed that one out of the lot showed a doubling of the edges on the back facets, something that spinels do not show. He had it examined by the Precious Stone Laboratory in London and its properties were found to be different from any known gem. Thus a new gem came to light in the cut stone rather than in the rough. To confirm this analysis, it was further examined by the Mineral Department of the British Museum.

It is a pale lavender to violet in color, similar to many spinels, and possesses the same hardness of 8. The specific gravity is 3.62, the refractive indices being 1.719 and 1.723 and the luster is vitreous. The chemical formula is MgBeAl4O8 which is between spinel and chrysoberyl.

Its origin is presumed to be Ceylon. As with the sinhalites, perhaps they will also be discovered in Burma.

Ulexite

Ulexite is extremely soft, being only 1 on the Mohs scale, but cabochon stones are known, some of which show a nice cat's-eye effect. The author has one, round in shape and weighing 9.27 carats. It is very similar to gypsum, which also gives us an attractive cat's-eye. Many are as large as 75 carats. Both stones are white and of a beautiful silky luster. The specific gravity is 1.65.

The mineral was named after the German chemist, G. L. Ulex, who rendered the first accurate analysis. It occurs in Iquique, Chile, Salinas de la Puna, Argentina; in West Africa, and in Nova Scotia. In the United States, it has been found in Esmeralda County, Nev. and San Bernardino County, Calif.

Violane

Violane is occasionally cut into cabochons of a lovely violet-blue, but it is not as important as the other rare gems.

Its chemical composition is close to diopside. The refractive index is 1.69, the specific gravity is 3.23, the hardness is 6 and the luster is waxy.

2.38 cts. soft, creamy yellow willemite from Franklin, New Jersey, Inventory #21783. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Willemite

Willemite does not often occur in faceting grade, but when it is found in that quality it cuts a lovely gem. Of particular interest is its phosphorescence under magnesium light or radium radiations. It yields handsome cabochons, some of which show a distinct cat's-eye effect when they possess sufficient oriented inclusions. If pure, it would be colorless, but it usually contains a little iron which renders it yellow. It was named after Willem I, King of the Netherlands, in 1830.

The chemical formula is Zn2SiO4 and it is of a vitreous luster. The specific gravity is 3.89 to 4.18, the hardness is 5½ and the refractive indices are 1.691 and 1.719. It is found at the Franklin Furnace mines in New Jersey in association with franklinite.

1.94 cts. zincite from New Jersey. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Zincite

Zincite is one of the world's rarest gems and one of the most beautiful. Its rich aurora-red hue is most pleasant to see. It is regrettable that it is comparatively soft, 4 to 4½ on the Mohs scale, and easily cleaved.

The world's largest zincite, formerly in the Bauer collection and now at the Smithsonian Institution, is an emerald cut gem of approximately 20 carats and of great beauty. Gems cut from this material regardless of size , are rare indeed.

It is a red oxide of zinc corresponding to the formula ZnO and usually containing a small amount of manganese. The more manganese it contains, the more orange it is in color.

It is highly refractive, the indices being 2.013 and 2.029 and is of an adamantine luster which adds to its beauty. The specific gravity is 5.68.

The only place where it has been found is in the zinc mines at Franklin Furnace, Sussex County, N. J., the same locality where Willemite is mined.