The Gem Spectrum is Pala International’s

free newsletter. Edited by Pala’s own Gabrièl Mattice,

it is filled with interesting articles on various aspects of gems

and minerals.

We

distribute The Gem Spectrum free within

the United States to members of the gem and

jewelry trades. If

you would like to be added to our mailing

list, please contact

us. We

distribute The Gem Spectrum free within

the United States to members of the gem and

jewelry trades. If

you would like to be added to our mailing

list, please contact

us.

The Reds have the Greens

When the first Russian stuck his

hand into the icy waters of the Ural Mountains’ Bobrovka River

and pulled out a handful of shiny green pebbles, little did he know

that he would be triggering an entirely new movement in jewelry. Originally

thought to be peridot, the gem proved to be green andradite garnet,

and was dubbed “demantoid” after its diamond-like properties.

Before long, the workshops of Carl Fabergé were crafting stunning

pavé pieces for the Czars. Even New York’s Tiffany had its

chief gemologist, George F. Kunz, off in Russia buying all the fiery

green gems he could get hold of.

Then,

just as quickly as it appeared, it vanished.

Overnight, the Bolshevik revolution turned

Russia upside down, and that included the country’s

gem trade. The Reds had no need for bourgeois

luxuries such as gems. Thus the brilliant green

pebbles lay dormant in the swamps and marshes,

waiting patiently for a new suitor.

It

took the late-1980’s fall of the Soviet

Union to shake more demantoid loose from the

Ural soil. With communism gone, the former

Reds found green to be very much to their liking.

Once again, demantoid emerged onto the world

gem market. Like reconnecting with a long-lost

lover, buyers were smitten again, and quickly

rekindled the passion for these Ural pearls.

In

the 1990’s, Pala International’s

William Larson worked closely with the Russians

at several mining areas, but even with modern

mining methods, demantoids remained elusive.

This lady was definitely playing hard-to-get.

That

changed in the summer of 2002. When prospectors

digging at the old Kladovka mine uncovered

a brand-spanking new vein, Larson received

a frantic call from his Russian partner, Nicolai

Kouznetsov. Nicolai pleaded with Larson to

get on the next plane over to Russia: “Come

now! I’ve got something here even better

than caviar…”

To

a caviar lover like Larson, that was pure catnip.

Just forty-eight hours later, he walked into

an Ekaterinburg sorting room and was stunned

by what he saw – a gemologist sat behind

a giant green mountain. Over 20 kg of

demantoid – more than the world had seen

since the time of the Czars – was spread

out for viewing. Larson could say only one

thing: “Great googly moogly! The Reds

have the greens.”

A Visit to Russia’s Demantoid Mines

by William Larson

It’s late August, 2002, and

I’m exhausted, flying Aeroflot from Los Angeles to Moscow and

then a domestic jet to Ekaterinburg, jumping-off point for the Ural

Mountain gem mines. Yes I’m tired, but – damn the torpedoes – somebody

has to do it. Why, you ask? Because the Reds have just dug up what

promises to be one of biggest finds of green in a century. Green as

in demantoid garnet, imperial gem of Fabergé and the Czars.

After

arrival, Vadim, the mine manager, meets us

and we drive out to the mines. In the Urals,

the mining season is short – just three

to four months – and only in the last

two weeks has the insect population come down

to bearable. It was at the Kladovka site that

demantoid was first found last century. Indeed,

researching that historic discovery is what

led Vadim and his team here.

Exploration started in May, but by July, they were on the verge of giving

up. Then, Mother Russia threw her sons a little treasure. Workers exposed

a vein and before long, green Ural pearls were being unearthed in unheard-of

quantities.

In

one vein, the green garnets have formed in

crystals and aggregates. The best pieces are

isolated in lines of nodules, glistening like

green, polished tears. These are up to a quarter

inch in diameter.

Above

the pit, pea-sized pieces of demantoid are

scattered across a piece of canvas in a spectacular

display of newly dug treasure. We marvel at

the scene, turning beautiful, crystal-clean

demantoids in our fingers. The likes of this

have hardly been seen since the time of the

Czars.

A

few of the rocks are broken up, revealing nodules

of an extraordinary green color. As the last

sunlight fades, we retire to camp, where a

barbecue has already begun. We take several

fine demantoid samples back, and display them

like hunting trophies on the dinner table.

That

evening, over a toast, our Russian friends

invite us to return again. As Nicolai raises

his glass, he winks at me and says: “I

love this business. We travel far and wide

in search of these charms of nature. And in

doing so, we are exposed to the charms of people

from opposite sides of the globe. Here’s

to our business…” We raise our

glasses once more…

Yes,

I will definitely be back for more. All in

all, it is one of my most memorable days in

prospecting.

|

Palagems.com Demantoid

Garnet Buying Guide

By Richard

W. Hughes

Introduction/Name. Demantoid

is the name given to the rich green variety of andradite garnet.

The gem was first discovered in Russia and the name is derived

from its diamond-like adamantine luster.

Color. While

the color of demantoid never equals that of the finest emerald,

an emerald-green is the ideal. The color should be as intense

as possible, without being overly dark or yellowish green.

The color of demantoid is believed to be due to chromium. It

should be noted that demantoid’s fire is best seen in

the lighter, less saturate gems. Thus the color preference

is a matter of individual taste. Some people will choose an

intense body color and less fire, while others prefer a lighter

body color and more fire.

Lighting. Demantoid

garnet generally looks best under daylight. Incandescent light

makes it appear slightly more yellowish green. Because of its

high dispersion, demantoid looks great in the same type of

lighting as diamond, i.e., multi-point (as opposed to diffuse)

lighting.

Clarity. In

terms of clarity, demantoid is relatively clean. Thus when

buying one should expect eye-clean or near-eye-clean stones.

Demantoids often contain radiating needle inclusions that are

termed “horsetails.”

Cut. In

the market, demantoids are found mainly as round brilliant

or cushion cuts. Cabochon-cut demantoids are not often seen.

Prices. Demantoid

is among the most expensive of all garnets, with prices similar

to those fetched by fine tsavorite (the other green garnet).

But like all gem materials, low-quality (i.e., non-gem quality)

pieces may be available for a few dollars per carat. Such stones

are generally not clean enough to facet. Prices for demantoid

vary greatly according to size and quality. At the top retail

end, they may reach as much as US$10,000 per carat.

Stone Sizes. Demantoid

is rare in faceted stones above 2 cts. Fine demantoids above

5 carats can be considered world-class pieces. Most stones

tend to be less than 1 ct.

Sources. The

original locality for demantoid was in Russia’s Ural

Mountains. Today, deposits of lesser material exist in Iran,

Italy and Namibia, but the Russian material remains the standard

by which the gem is judged.

Enhancements. Some

demantoid garnet is heat-treated to improve the color. The

resulting stones are stable under normal wearing conditions.

Imitations. Demantoid

garnet has never been synthesized, but a number of imitations

exist. These include green glass and green YAG.

Properties of Demantoid Garnet

| |

Demantoid Garnet (a variety

of andradite garnet) |

| Composition |

Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3 |

| Hardness (Mohs) |

6.5 to 7 |

| Specific Gravity |

3.84 |

| Refractive Index |

1.888; Singly refractive |

| Crystal System |

Cubic |

| Colors |

Light to deep green |

| Pleochroism |

None |

| Dispersion |

0.057; this is among the highest

of all gems, even higher than diamond |

| Phenomena |

None |

| Handling |

Ultrasonic: generally safe,

but risky if the gem contains liquid inclusions

Steamer: not safe

The best way to care for demantoid garnet is to clean it with

warm, soapy water. Avoid exposing it to heat or acids. |

| Enhancements |

Some demantoid is heat treated

to improve the color |

| Synthetic available? |

No |

Further reading

For

more on Russia’s demantoid

mines, see Gabrièl Mattice’s Gem

Spectrum Newsletter, Vol. 4,

No. 1 |

|

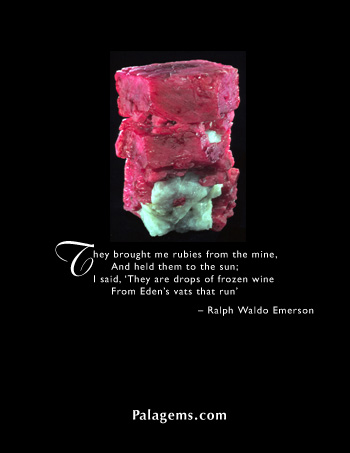

Big

Mama’s in the House

One of the most extraordinary ruby specimens ever to emerge

from Burma’s fabled Mogok Stone Tract was recently acquired

by Pala International. Pictured at left, this crystal weighs

an incredible 10,100 carats. We have affectionately name it “Big

Mama.”

In the world of rubies, Mogok has no peer, with the finest

pigeon’s blood reds so rare that, above two carats, they

easily surpass diamond in price. Crystals of this quality are

equally rare. Big Mama is available for viewing by appointment.

|

|

|