Burmese Jade, Part 2

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Mr. Hughes is

an author and gemologist in Fallbrook, California. Mr. Galibert (FGA,

hons.; ING, AG) is a gemologist and Hong Kong-based dealer

in colored stones and pearls. Mr. Bosshart is

chief gemologist, Research and Development, at the Gübelin

Gem Lab, Lucerne, Switzerland. Mr. Ward,

a gemologist, writer, and photographer, owns Gem Book Publishing,

Bethesda, Maryland. Dr. Thet Oo is a gemologist and Yangon-based

dealer in colored stones. Mr. Smith is

a gemlogist and Bangkok-based dealer in colored stones. Dr. Tay is

president of Elvin Gems and Far Eastern Gemmological Lab of

Singapore. Dr. Harlow is

curator of Gems and Minerals at the American Museum of Natural

History, New York City.

Acknowledgments and references appear at the end of Part 2 of this article. Also included is a Palagems.com Jadeite Buying Guide.

© 2000 Richard W. Hughes

Note: Portions of this article originally

appeared in Gems & Gemology, Vol.

36, No. 1, pp. 2–26.

Abstract: Part 1 of this article discussed the history, location and geology of Burma’s jadeite mines, along with a description of the deposits themselves and mining methods. In this concluding part, the trading, grading and cutting of Burmese jadeite is detailed. Also included is a description of the various types of enhanced jadeite and assembled jadeites.

From the time jade is won in the Jade

Mines area until it leaves Mogaung in the rough for cutting

there is much that is underhand, tortuous and complicated,

and much unprofitable antagonism. In my opinion the whole

business requires cleansing, straightening and the light

of day thrown on it.

Major F.L. Roberts

Former Deputy Commissioner, Myitkyina (from Hertz, 1912)

Perhaps

no other gemstone has the same aura of mystery as does jadeite.

The mines’ remote location in Upper Burma is certainly

a factor (as discussed in Part

1 of this article). But most important is that jade connoisseurship

is almost strictly a Chinese phenomenon. The people of the

Orient have developed jade appreciation to a degree found

nowhere else in the world, but this knowledge is largely

locked away in arcane, non-Roman alphabet texts, adding further

to the inscrutable nature of this precious stone.

Part 2 of this article continues to draw back the

curtain on this enigmatic precious stone, revealing the manner in which Burmese

jade is traded, graded, cut, treated and faked. Since the technical aspects of

Burmese jade have already been extensively covered in the literature (Hobbs,

1982; Fritsch et al., 1992; Chunyun Wang, 1994), emphasis will be on the obscure

and anecdotal. For if there is one concept more important than any other, it

is that an understanding of jade is not limited to the technical or exacting,

but is about feeling, a feeling for a culture, a feeling for the textural, ephemeral

qualities that makes the study of jade unlike no other in the world of precious

stones.

|

| Figure 16. A room with a view U Tin Ngwe, who went from taxi driver to jade kingpin almost overnight, stands atop a small fortune of jade at his Hpakan home. Photo © Olivier Galibert. |

The color of joss

It is said that success in the

jade business involves “joss” (luck). That’s

akin to calling a lottery ticket an investment in the future.

The jade trade is not about luck, it’s about strapping

your hopes and dreams onto the rim of the roulette wheel

and letting the creator give it a long, hard spin. Just how

much joss is involved is illustrated by the tale of U Tin

Ngwe, one of Hpakan’s many laopan (kingpins).

Ironically enough, he got his start in the business while

working as a taxi driver. One day, a local jade trader fare

offered him a spin of the green wheel, in the form of a grab

bag of jade boulders. Picking up each piece, he studied them

carefully. “Why not?” he thought, “I feel

lucky,” and handed over 3,000 kyat ($23) for the heaviest

boulder in the lot. He felt even luckier after selling the

piece to another trader for 650,000 kyat ($5000). And that

trader felt even luckier still after selling the exact same

piece for over 3,000,000 kyat ($23,000). “Hmm,” he

thought to himself, “this is interesting.” It was

so interesting that, today, U Tin Ngwe owns several jade

mines and is one of the biggest traders in the valley. When

the steel ball finally came to rest, it had stopped at his

number (U Tin Ngwe, pers. comm. to RWH, OG, MS & TO,

June, 1996).

Types of Jadeite Rough. Traders

classify jadeite rough first according to where it was mined.

River jade, the jadeite recovered from alluvial deposits

in and along the Uru River, occurs as rounded boulders with

a thin skin (figure 19, top left). In contrast, mountain

jade (found away from the river) appears as rounded boulders

with thick skins (figure 19, bottom left). The irregular

chunks of jadeite quarried directly from in situ deposits,

such as those at Tawmaw, represent a third type (figure 19,

right). According to Chhibber (1934b), “it is locally

believed that jadeite mined from the rivers and conglomerate

is more ‘mature’ than that of Tawmaw.”

Because weathering usually removes damaged or altered

areas, the best qualities are usually associated with river jade. In addition,

the thin skin – and, therefore, greater likelihood of “show points” – in

river jade allows a more accurate estimate of the quality and color within (figure

10). Mountain jade boulders tend to be clouded by a thick layer (termed “mist” by

Chinese traders) between the skin and the inner portion of the boulder (Ho, 1996;

figure 14).

|

| Figure 17. Vendors work the morning jadeite market in Mandalay. Photo © 2000 Fred Ward. |

The occurrence of green and lavender jadeite is independent of the deposit type, but reddish orange to brown jadeite is found only in those boulders that are recovered from an iron-rich soil. The reddish orange results from a natural iron-oxide staining of the skin of the porous jadeite, and is sometimes intensified with heat (Chhibber, 1934b).

Jadeite Trading in Burma

Contributing to the aura

of mystery that surrounds jadeite is the distinctive system

of jadeite commerce in Burma. This includes the markets for

rough jadeite, the boulder “taxes,” and evaluation

of the rough. The Chinese, who dominate the market for fine

jadeite both within and outside of Burma, play an important

role in this system.

Rough Jade Markets. Most

of Burma’s open jadeite markets are small, perhaps because

the idea of free trade is still somewhat new. Nevertheless,

there are markets in Hpakan, Lonkin, and Mogaung.

Burma’s largest jade market is in south Mandalay

(figure 12), a city that is said to operate on the three “lines” – white

(heroin), red (ruby), and green (jade; Cummings and Wheeler, 1996). Trading is

conducted in several places along 86th Street (Kammerling et al., 1995). Here,

every morning, hundreds of people can be observed haggling over jadeite. Just

south of the markets, cutting workshops are also found. Despite the toughness

of jadeite, many cutters in Mandalay still shape cabochons on boards that have

been coated with carborundum and hard wax, and then polish the jadeite on bamboo

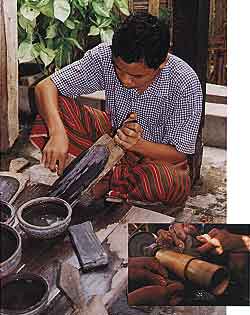

lathes (figure 13).

|

Figure 18. In Mandalay, cutters still use a board coated with a mixture of carborundum (of various grits) and hard wax to shape cabochons (photo by Mark Smith). They then polish jadeite on bamboo lathes, often without any abrasive (inset photo © 2000 Fred Ward). |

Taxes. Written on each jadeite boulder we saw in the markets was a registration number and the weight of the boulder; this signified that tax had been paid on the piece. A government-appointed committee evaluates the boulders in Hpakan and then levies a tax of 10% of the appraised value. Even though a boulder has been officially appraised, its purchase is inevitably a gamble for the trader.

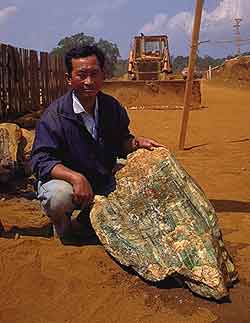

Types of Jadeite Rough. Traders classify jadeite rough first according to where it was mined. River jade, the jadeite recovered from alluvial deposits in and along the Uru River, occurs as rounded boulders with a thin skin (figure 14, top left). In contrast, mountain jade (found away from the river) appears as rounded boulders with thick skins (figure 14, bottom left). The irregular chunks of jadeite quarried directly from in situ deposits, such as those at Tawmaw, represent a third type (figure 14, right). According to Chhibber (1934b), “it is locally believed that jadeite mined from the rivers and conglomerate is more ‘mature’ than that of Tawmaw.”

|

|

|

|

| Figure 19. Top left: This jadeite boulder shows the relatively thin skin and potentially good color that is usually associated with “river jade.” Although from the outside this appears to be a normal jadeite boulder, oxidants that entered through cracks on the surface have produced a large area of discoloration. Bottom left: Note the thick yellow “mist” around the jadeite in this boulder of “mountain jade.” Right: A key advantage to jadeite taken from in situ deposits is that the quality of the material is readily apparent. Photos © Richard W. Hughes. | |

Because

weathering usually removes damaged or altered areas, the best

qualities are usually associated with river jade. In addition,

the thin skin – and, therefore, greater likelihood of “show

points” – in river jade allows a more accurate estimate

of the quality and color within (figure 10). Mountain jade

boulders tend to be clouded by a thick layer (termed “mist” by

Chinese traders) between the skin and the inner portion of

the boulder (Ho, 1996; figure 19).

The occurrence of green and lavender jadeite is

independent of the deposit type, but reddish orange to brown jadeite is found

only in those boulders that are recovered from an iron-rich soil. The reddish

orange results from a natural iron-oxide staining of the skin of the porous jadeite,

and is sometimes intensified with heat (Chhibber, 1934b).

Evaluating Rough – The Skin Game

One of the greatest challenges

in the jadeite trade is the evaluation of a material

that is covered by a skin that typically hides all

traces of the color and clarity/diaphaneity that

lies within. This skin can be white, yellow, light

to dark brown, or black.

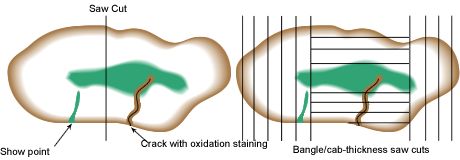

According to traders and miners with whom we spoke,

they look first for any color spots or show points in those areas where the skin

is thin enough to see through. Evidence of surface cracks is also important,

as fractures often extend into the boulder and open a path for oxidants to discolor

the interior (see figure 19, top left). Such fractures can have a strong negative

impact on the value of the material.

|

| Figure 20. The “Golden

Hand” To get a better idea of the quality of color in this boulder, the dealer places a metal plate at the far side of a small area with potential and then uses a penlight to illuminate it. Photo © Richard W. Hughes. |

If a show

point is not available or is inadequate, the owner will sometimes

polish an “eye” or maw (“cut” or “window”)

through the skin (see figure 1). First, though, the owner will

carefully examine the piece to determine the best location

because, if good color shows through the window, the boulder’s

value rises tremendously. Conversely, if poor color is revealed,

the value drops. Such windows should be checked for artificial

coatings or other tampering, which may give a false impression

of the material within (see, e.g., Johnson and Koivula, 1998).

If there

are no show points or windows, a common technique is to wet the

surface of the boulder in the hope that the underlying color

will come through (again, see figure 10). Where even a little

color is suggested, traders also use small metal plates in conjunction

with a penlight. They place the edge of the plate on what appears

to be a promising area and then shine the penlight from the side

farthest from the eye (figure 20). The plate removes the glare

from the light, so any color can show through. If light penetrates

the underlying jadeite, this is an indication of good transparency.

But, due to jadeite’s aggregate structure, the color will

have been diffused from throughout the boulder by the scattering

of light. Thus, even a small area of rich color can make a piece

appear attractive through the window. To see an example of this,

take a jadeite cabochon that is white, but has a small green

vein or spot. Shine a penlight or fiber-optic light through the

cab from behind. Voilà, the entire cabochon appears green.

To reduce the risk of such a speculative business,

much jadeite rough is simply sawn in half; this is the approach used at the government-sponsored

auctions in Yangon. However, parting a boulder down the middle has the danger

of cutting right through the center of a good area. A more careful method of

evaluating jadeite boulders involves grinding away the skin (Lee, 1956). Alternatively,

some owners gradually slice the boulder from one end (perhaps the thickness of

a bangle, so that each slice can be used for bangles or cabochons) until they

hit good color. They then repeat the process from the opposite end, the top,

and the bottom, until the area of best color is isolated (figure 21).

|

Certain experienced jade traders are said to have a “golden hand” when it comes to judging jade boulders; that is, they are able to predict, by studying the outside of the boulder, what the inner color will be. Nevertheless, the jade trade seems to be a competition between sellers, who want to show the best spot of color and not disclose the remaining bad points, and buyers, who want to imagine a fine interior in a stone that shows poorly in the few maws.

Evaluation of Finished Jadeite

The evaluation of finished jadeite

has been discussed by Healy and Yu (1983), Ng and Root (1984),

and, most recently, by Christie’s (1995b), Ho (1996),

and Ou Yang (1995, 1999). The basic system is summarized

below in a somewhat simplified fashion. Although we use the

concepts discussed in the above publications, as much as

possible we have chosen language that is comparable to that

used for other colored stones.

While a number of fanciful terms have been used

to describe jadeite, its evaluation is similar to that of other gemstones in

that it is based primarily on the “Three Cs” – color, clarity,

and cut (fashioning). Unlike most colored stones, the fourth “C” – carat

weight – is less important than the dimensions of the fashioned piece. However,

two additional factors are also considered – the “Two Ts” – translucency

(diaphaneity) and texture. In the following discussion, Chinese terms for some

of the key factors are given in parentheses, with a complete list of Chinese

terms for various aspects of jade given in table 1.

|

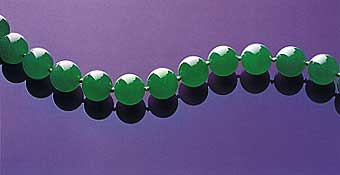

Color (se). This is the most important factor in the quality of fashioned jadeite. As per standard color nomenclature, jadeite’s colors are best described by breaking them down into the three color components: hue (position on the color wheel), saturation (intensity), and tone (lightness or darkness). Color distribution must also be taken into account. The necklace in figure 23 is an excellent example of top-quality hue, saturation, tone, and color distribution.

- Hue (zheng): Top-quality jadeite is pure green. While its hue position is usually slightly more yellow than that of fine emerald and it never quite reaches the same intensity of color, the ideal for jadeite is a fine “emerald” green. No brown or gray modifiers should be present in the finished piece.

- Saturation (nong): This is by far the most important element of green and lavender jadeite color. The finest colors appear intense from a distance (sometimes described as “penetrating”). Side-by-side comparisons are essential to judge saturation accurately. Generally, the more saturated the hue is, the more valuable the stone will be. A related factor is referred to as cui by the Chinese. Colors with fine cui are variously described as brilliant, sharp, bright, or hot. This is the quality that makes “shocking” pink shocking and “electric” blue electric.

- Tone (xian): The ideal tone is medium – not too light or too dark.

- Distribution (jun): Ideally,

color should be completely even to the unaided eye, without

spotting or veins. In lower qualities, fine root- or vein-like

structures that contrast with the body color of the stone

may be considered attractive. However, dull veins or roots

are less desirable. Any form of mottling, dark irregular

specks, or blotches that detract from the overall appearance

of the stone will reduce the value.

Figure 23. This necklace, which contains a total of 65 beads (7.8–9.8 mm in diameter) and two matching hoops, illustrates the optimum “vivid emerald green” color in fine jadeite. Note also the very fine “old mine” texture and translucency. Photo courtesy of and © Christie’s Hong Kong and Tino Hammid. TABLE 1. Chinese jade nomenclature (Based on Ho, 1996) Chinese name Meaning Yu Chinese word for jade Ruan yu Nephrite Ying yu “Hard jade” or jadeite Fei-ts'ui (feicui) “Kingfisher” jadeite Lao keng “Old mine” jadeite – fine texture Jiu keng “Relatively old mine” jadeite – medium texture Xin keng “New mine” jadeite – coarse texture Ying Jadeite type with the highest luster and transparency Guan yin zhong Semi-translucent, even, pale green jadeite Hong wu dong Lesser quality than guan yin zhong, with a pale red mixed with the green Jin si zhong “Golden thread” jadeite: A vivid green color is spread evenly throughout the stone. This type is quite valuable. Zi er cui High-grade jadeite mined from rivers. Because of its high translucency, it is also known as bing zhong (“ice”). Lao keng bo li zhong Old-mine “glassy” (finer texture, more translucent) jadeite (see figure 24). In Imperial green, this type is the most valuable jadeite. Fei yu Red jadeite, named after a red-feathered bird Hong pi “Red skin” jadeite, cut from the red skin of a boulder (see figure 1) Jin fei cui Golden or yellow jadeite Shuangxi Jadeite with both red and green Fu lu shou Jadeite with red, green, and lavender Da si xi Highly translucent jadeite with red, green, lavender, and yellow Wufu linmen Jadeite with red, green, lavender, and yellow, as well as white as the bottom layer

Clarity. This

refers to imperfections that impair the passage of light.

The finest jadeite has no inclusions or other clarity defects

that are visible to the naked eye.

Typical imperfections are mineral inclusions, which

usually are black, dark green, or brown, but may be other colors. White spots

also are common, as are other intergrown minerals. The most severe clarity defects

in jadeite are fractures (healed or unhealed), which can have an enormous impact

on value because jadeite symbolizes durability and perfection (Ou Yang, 1999).

|

Translucency (diaphaneity). This

is another important factor in evaluating quality. The best

jadeite is semi-transparent; opaque jadeite or material with

cloudy patches typically has the least value.

It is interesting to note that even if the overall

color is uneven or low in saturation, jadeite can still be quite valuable if

it has good transparency. The “glass” jade bangles in figure 24 sold

for U.S. $116,000 at the November 1999 Christie’s Hong Kong auction.

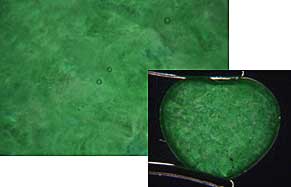

Texture (zhong). In

jadeite, texture is intimately related to transparency. In the

authors’ experience, typically the finer the texture is,

the higher the transparency will be. Further, the evenness of

the transparency depends on the consistency of the grain size.

Our observations also suggest that coarse-grained jadeite tends

to have more irregularities, blotches, or discolorations.

Texture is key to the classification of fashioned

jadeite into three categories: fine (lao keng, or “old mine”),

medium (jiu keng, or “relatively old mine”), and coarse (xin

keng, or “new mine”), as described by Ho (1996). “Old mine” is

considered the best, with the finest texture, translucency, and luster (again,

see figures 24 and 25). Note that Chinese jadeite dealers also use the terms “old

mine” (keng zhong) and “new mine” (xin shan zi) to

describe rough. This is not really an expression of the age or location where

the jadeite is mined, but more an indication of texture and translucency, with

old-mine jadeite having a higher quality, being of finer grain size, and having

greater luster and translucency (Ho, 1996). It probably derives from the belief

that jade that is more compact and of finer texture is of greater age.

| Table 2: Burmese jadeite nomenclature (based on Chhibber, 1934) | |

| Burmese name | Meaning |

| Kyauk sein (kyauk = stone; sein = green) | Burmese word for jadeite |

| Mya yay or yay kyauk (Chinese = kingfisher = fei-ts’ui ) | First grade green; bright, intense emerald green; used for expensive jewelry, such as cabochons, rings, necklaces, earrings, etc. |

| Shwe lu | Second grade green; light green jadeite with bright green spots and streaks; also used for expensive jewelry, such as cabochons, rings, necklaces, ear rings, etc. |

| Lat yay | Third grade; clouded jadeite, used in making bracelets, buttons, hatpins, etc. |

|

Kyauk amè (English = chloromelanite) |

Dark green, appearing black except when thinly cut. This material is rich in iron, and is used for making buttons, bars for brooches, etc. |

| Konpi | Red or brownish, found in boulders embedded in red earth |

| Hua hsueh tai tsao (Chinese; “moss entangled in melting snow”) | White with veins of shaded green |

| Kyauk atha | Translucent white, used for bracelets, pipe stems, plates, spoons, etc. |

| Pan tha | Brilliant white, translucent, and opaque to a certain extent |

| Maw-sit-sit (English = maw-sit-sit; a rock mixture of kosmochlor, natrolite and albite) | Medium to dark green, mottled; ornamental gem material; soft and brittle |

Fashioning. More

so than for most gem materials, fashioning plays a critical

role in jadeite beauty and value. Typically, the finest qualities

are cut for use in jewelry – as cabochons, bracelets,

or beads. Cutters often specialize: one may do rings, another

carvings, and so on.

Polish is particularly important with jadeite.

Fine polish results in fine luster, so that light can pass cleanly in and out

of a translucent or semi-transparent piece. One method of judging the quality

of polish is to examine the reflection of a beam of light on the surface of a

piece of jadeite. A stone with fine polish will produce a sharp, undistorted

reflection, with no “orange-peel” or dimpling visible.

Following are a few of the more popular cutting

styles of jadeite.

Cabochons. The

finer qualities are usually cut as cabochons (see figure

1). One of the premium sizes – the standard used by

many dealers’ price guides – is 14 x 10 mm (Samuel

Kung, pers. comm., 1997). Material used for cabochons is

generally of higher quality than that used for carvings (Ou

Yang, 1999), although there are exceptions.

With cabochons, the key factors in evaluating cut

are the contour of the dome, the symmetry and proportions of the cabochon, and

its thickness. Cabochon domes should be smoothly curved, not too high or too

flat, and should have no irregular flat spots. Proportions should be well balanced,

not too narrow or wide, with a pleasing length-to-width ratio (Ng and Root, 1984).

The best-cut cabochons have no flaws or unevenness of color that is visible to

the unaided eye.

Since the 1930s, double cabochons, shaped like

the Chinese ginko nut, have been considered the ideal for top-grade jadeite,

since the convex bottom is said to increase light return to the eye, thus intensifying

color (Christie’s, 1996). Stones with poor transparency, however, are best

cut with flat bases, since any material below the girdle just adds to the bulk

without increasing beauty. Hollow cabochons are considered least valuable (Ou

Yang, 1999).

Traditionally, when fine jadeite cabochons are

mounted in jewelry, they are backed by metal with a small hole in the center.

The metal acts as a foilback of sorts, increasing light return from the stone.

Also, with the hole one can shine a penlight through the stone to examine the

interior, or probe the back with a toothpick to determine the contours of the

cabochon base (Ng and Root, 1984). When this hole is not present, one needs to

take extra care, as the metal may be hiding some defect or deception.

|

Beads. Strands of uniform jadeite beads are in greater demand than those with graduated beads. The precision with which the beads are matched for color and texture is particularly important, with greater uniformity resulting in greater value (figure 25). Other factors include the roundness of the beads and the symmetry of the drill holes. Because of the difficulties involved in matching color, longer strands and larger beads will carry significantly higher values. Beads should be closely examined for cracks. Those cracked beads of 15 mm diameter or greater may be recut into cabochons, which usually carry a higher value than a flawed bead (Ng and Root, 1984).

Bangle Bracelets. Bangles are one of the most popular forms of jadeite jewelry, symbolizing unity and eternity. Even today, it is widely believed in the Orient that a bangle will protect its wearer from disaster by absorbing negative influences. For example, if the wearer is caught in an accident, the bangle will break so that its owner will remain unharmed. Another common belief is that a spot of fine color in a bangle may spread across the entire stone, depending on the fuqi – good fortune – of the owner (Christie’s, 1995a). In the past, bangles (and rings) were often made in pairs, in the belief that good things always come in twos (Christie’s, 1997).

|

Because a single-piece bangle requires a large quantity of jadeite relative to its yield, prices can be quite high, particularly for fine-quality material. The bangle in figure 26 sold for US$2,576,600 at the Christie’s Hong Kong November 1999 auction. Multi-piece bangles are worth less than those fashioned from a single piece, because the former often represent a method of recovering parts of a broken bangle. Mottled material is generally used for carved bangles, as the carving will hide or disguise the imperfections. When a piece is carved from high-quality material, however, it can be a true collector’s item (Ng and Root, 1984).

Huaigu (pi). The Chinese symbol of eternity, this is a flat disk with a hole in its center, usually mounted as a pendant or brooch. Ideally, the hole should be one-fifth the diameter of the entire disk and exactly centered. Small pairs are often used in earrings or cufflinks (figure 27).

|

|

|

Carvings. For the most part, the jadeite used in carvings is of lower quality than that used for other cutting styles, but nevertheless there are some spectacular carved jadeite pendants and objets d’art. The intricacy of the design and the skill with which it is executed are significant factors in determining the value of the piece. Carving is certainly one area where the whole equals more than the sum of the parts.

Recut Recovery Potential. As with many other types of gems, the value of poorly cut or damaged pieces is generally based on their recut potential. For example, it might be possible to cut a broken bangle into several cabochons. Thus, the value of the broken bangle would be the value of the cabochons into which it was recut (Ng and Root, 1984). If three cabochons worth $500 each could be cut from the bangle, its value would be about $1,500.

Enhancements and Imitations. Enhancements.

Jadeite historically has been subjected to various enhancements

to “finish” it, “clean” surface and interior

stains, and even dye it to change the color altogether. In

recent years, a three-part – A through C – classification

system has been used in Hong Kong and elsewhere to designate

the treatment to which an item has been subjected (Fritsch

et al., 1992).

A-Jade is jadeite that has not been treated in

any way other than cutting and polishing. Surface waxing is generally considered

part of the “traditional” finishing process. Used to improve luster

and fill surface fractures and pits, wax dipping is the final step in finishing

virtually all cut jadeite (figure 30).

|

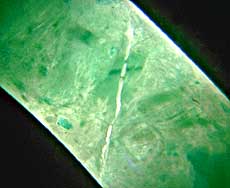

As noted above, much jadeite is discolored by rust-like oxidation stains. B-Jade is jadeite that has been soaked in chemical bleaches and/or acids for an extended period to remove brown or yellow impurities from between grain boundaries and cracks. Because this treatment process leaves voids in the jadeite, the bleached jadeite is subsequently impregnated with paraffin wax or, most commonly, a clear polymer resin (figure 31). The result is usually a significant improvement in both transparency and color. However, detection of this enhancement generally requires infrared spectroscopy, a sophisticated technique that usually must be performed in a gemological laboratory. (See Fritsch et al., 1992, for a full description of both the treatment and its identification.)

|

C-Jade,

jadeite that has been artificially stained or dyed, also

has a long history. Green, lavender, and even orange-brown

(Wu, 1997) colors are produced by staining suitable pale-colored

material with vegetable or other organic dyes, a process

that has been performed on jadeite since at least the 1950s.

The methods used in Hong Kong have been described by Ehrmann

(1958), Ng and Root (1984), and Ho (1996).

The authors have seen fading in both dyed green

and dyed lavender jades, but the green dyes tend to fade more readily. Generally,

dyeing is identified with a microscope and a spectroscope: The color tends to

concentrate in veins throughout the stone, in surface cracks, and along grain

boundaries; also, a broad band from about 630 to 670 nm in the red region of

the visible spectrum is considered proof of dye in green jadeite (see, e.g.,

Hobbs, 1982). Some of the newer dyes may also show a weaker band at 600 nm. Because

some stones are only partially dyed, the entire piece must be checked.

Assembled Stones and Other Imitations. There are many assembled stones that resemble jadeite. These include triplets made by taking a highly translucent piece of pale-colored jadeite and cutting it as a thin, hollow cabochon. A second cabochon is cut to fit snugly into the first, with a green cement or jelly-like substance placed between the two. A third, flat piece of jadeite of lower transparency is then cemented onto the base. Another type of assembled stone is that made with a piece of extremely dark green jadeite hollowed out to eggshell thickness. This allows light to pass through, creating the appearance of fine Imperial jade (figure 32). To strengthen the piece, the hollow back is filled with an epoxy-like substance; and to hide the deception, the piece is then mounted in jewelry with the back hidden (Kammerling and McClure, 1995; Hughes and Slavens, 1999).

|

At Mandalay’s jadeite market, two of the authors (RWH and FW) noticed many pale jadeite cabochons that had been coated on their upper surface with green plastic (figure 33) (Hughes, 1987). Another convincing imitation is produced by first placing a dye layer on the piece and then overlaying it with varnish (Koivula et al., 1994).

|

|

Assembled Rough. The

authors have observed several types of assembled rough. One

type involves grinding away the skin of a jade boulder, painting

or staining the surface green, and then “growing” a

new skin via immersion in chemicals, which deposit a new oxidation

layer on the outside. Unlike the skin on genuine jadeite boulders,

which is extremely tough and can be removed only by grinding,

the fake skins are soft and easily taken off. Another type

involves sawing or drilling a core out of a jade boulder, inserting

a green filling and a reflector, and then covering the hole

with a combination of epoxy and grindings from the surface

of jade boulders.

In certain cases, even the cut windows of jadeite

boulders may be faked. One method involves simply applying a superficial stain

to the window area. Another is to break off a chip, stain it green and glue it

back onto the boulder. When a window is then cut on the boulder, it “reveals” a

fine green color.

Jadeite Auctions

At many of the early auctions, buyers would examine

the jade and make offers to the seller using hand signals under

a handkerchief (see, e.g., Ng and Root, 1984, for an illustration

of these “finger signs”). This system, which has

been used historically at the mines as well as in China, allows

the seller to realize the highest price for each lot without

letting others know the actual amount paid. Thus, the buyer

can resell the material at whatever price the market will bear

(Allan K. C. Lam, pers. comm., 1997). This technique can still

be seen every morning in Hong Kong’s Canton Road jade

market. However, it is no longer used at the jadeite mines.

Recognizing the importance of the market for jadeite

jewelry, Sotheby’s Hong Kong initiated specialized jadeite jewelry auctions

in November 1985 with just 25 pieces. Christie’s Hong Kong followed suit

in 1994 with a sale of 100 pieces. Since then, thousands of pieces have been

auctioned off by Christie’s Hong Kong in what are now biannual auctions

of magnificent jadeite jewelry.

To give some idea of the importance of this market,

the Mdivani necklace (Lot 898), which contains 27 beads (15.4 to 19.2 mm in diameter),

sold for US$3.88 million at the October 1994, Christie’s Hong Kong sale.

The record price for a single piece of jadeite jewelry was set at the November

1997 Christie’s Hong Kong sale: Lot 1843, the “Doubly Fortunate” necklace

of 27 approximately 15 mm jadeite beads, sold for US$9.3 million (again, see

figure 25). Indeed, out of the top ten most expensive jewels sold worldwide by

Christie’s in 1999, five out of ten were jadeite, including three of the

top four (1999: Christie’s captures its…, n.d.). These auctions clearly

show that jadeite is among the most valuable of all gemstones.

Summary

Jade (primarily nephrite) has been prized in China for thousands of years.

Yet the finest jade – jadeite – has been a part of the Chinese

culture only since the late 18th century, when the mines in what is today

north-central Burma were opened. As the first Western gemologists to enter

the remote jadeite mining area in more than three decades, the authors witnessed

tens of thousands of miners working the rivers, Uru conglomerate, and in-situ

deposits in search of jadeite. Backhoes, trucks, pneumatic drills, and rudimentary

tools are all enlisted in the different mining operations.

Identification of jadeite in a boulder requires

both luck and skill (and the presence of windows or “eyes”), although

many dealers simply grind off the skin of the boulder or cut it in half. Once

the taxes are paid (and the boulders marked accordingly), the rough jadeite is

sold primarily to Chinese buyers who carry it to Hong Kong and elsewhere in China

for resale and fashioning. Color, clarity, transparency, and texture are the

key considerations in evaluating fine jadeite, which is cut into many different

forms – such as cabochons, bangles, saddle rings, disks, and double hoop

earrings, as well as carved for use as pendants or objets d’art.

The finest Imperial jadeite is a rich “emerald” green

color that is highly translucent to semi-transparent, with a good luster. With

both rough and fashioned jadeite, purchasers must be cautious about manufactured

samples or enhancements. Although “waxing” of jadeite has been an accepted

practice for many years, the more recent “B” jade – by which the

stone is cleaned with acid and then impregnated with a paraffin wax or polymer – will

affect the value of the piece. Jadeite is often dyed, and plastic-coated cabochons

were seen even in the Burmese markets. Also of concern, because of durability,

are those jadeite pieces that have been cut very thin and then “backed” or

filled with an epoxy-like substance.

The prices received at the Hong Kong auctions held

specifically for jade indicate that for many people, especially in the Orient,

jadeite holds a higher value than almost any other gem material. From humble

beginnings as an encrusted boulder to its exquisite emergence as a fashioned

piece, jadeite truly is an inscrutable gem.

|

Conclusion: Spinning the jade wheel

If jade is not polished, it cannot be made worth anything. If man does not suffer trials, he cannot be purified.

Chinese proverb (as quoted by Gump, 1962)

In jade,

as in roulette and life itself, some win, some lose. Few who

lived in Bangkok in the late-1970’s can forget the story

of one trader who invested a small fortune in a promising jade

boulder. Others were also eager to possess it; one went so

far as to offer him several times his money. But he refused

to sell. Instead, giving the wheel a long, hard spin, he cut

the stone open himself. Alas, it was not to be. The polishing

wheel revealed no purity whatsoever, just a worthless lump.

When the steel ball finally came to rest, it stopped right

between his eyes – exiting from the muzzle of the weapon

with which he blew out his brains.

Yes, the jade trade is a crapshoot, a spin of the

roulette wheel. Some may win, more still will lose. But as long as the green

stone continues to be taken from the soil in Upper Burma, there will be a steady

line of players, ready to suffer for their art, ever ready to trace the green

line, in search of color, in search of purification, in search of feeling – building

the bridge to heaven, one pebble, one stone at a time.

![]()

Acknowledgments

Richard Hughes thanks Robert

Weldon and Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone for making

his first trip possible. Thanks also to Robert Frey for a

careful reading of the manuscript, Elaine Ferrari-Santhon

and Dona Dirlam of the Richard T. Liddicoat Library and Information

Center for helpful research on jade, and Dr. Edward Gübelin,

whose earlier accounts of the mines provided inspiration.

Olivier Galibert thanks the following: C. K. Chan of Chow

Tai Fook, Edmond Chin of Christie’s Hong Kong, Garry

Dutoit of the AGTA Gemological Testing Center, Lisa Hubbard

of Sotheby’s Hong Kong, Benjamin So and Judith Grieder

Jacobs of the Hong Kong Jade and Jewellery Association, Samuel

Kung, Dominic Mok, and Eric Nussbaum of Cartier Geneva. George

Bosshart thanks his wife, Anne, an outstanding trekking companion.

Fred Ward and Richard Hughes thank Georg Muller, television

producer and friend with enough foresight, insight, and connections

to get his colleagues and himself into the Burmese jade localities.

George Harlow and Richard Hughes also thank William

Larson of Pala International for his help and advice.

Photographer Tino Hammid was

very helpful in providing photos of the Christie’s Hong

Kong auction items, and Harold and Erica Van Pelt supplied

figures 1 and B-3, as well as the cover photo.

A special thanks is also due to Alice Keller, Brendan

Laurs, Stuart Overlin, Karen Myers and the other staff of Gems & Gemology, for

the fantastic job they did in fact-checking, editing and laying out the original

version of this article.[not reproduced here]

Dedication

This article is dedicated to our

colleague and co-author, Dr. Thet Oo, who suffered a series

of strokes after his second trip to the mines. A finer traveling

companion does not exist. We wish him a speedy recovery. (back

to top)

References

- The art of feeling jade (1962) The Gemmologist, Vol. 31, No. 372, pp. 131–133 (reprinted from Gems and Minerals, No. 286, July 1961, pp. 28–29).

- Bender F. (1983) Geology of Burma. Gebrüder Borntraeger, Berlin, 260 pp.

- Bleeck A.W.G. (1907) Die Jadeitlagerstätten in Upper Burma. Zeitschrift für praktische Geologie, Vol. 15, pp. 341–365.

- Bleeck A.W.G. (1908) Jadeite in the Kachin Hills, Upper Burma. Records, Geological Survey of India, Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 254–285.

- Burma Action Group (1996) Burma: The Alternative Guide. London, Burma Action Group, 2nd ed., 48 pp.

- Chhibber H.L. (1934a) The Geology of Burma. Macmillan, London, 538 pp.

- Chhibber H.L. (1934b) The Mineral Resources of Burma. Macmillan, London, 320 pp.

- Christie’s (1995a) Magnificent Jadeite Jewellery. Catalog for Christie’s Hong Kong, May 1, 1995 auction.

- Christie’s (1995b) Magnificent Jadeite Jewellery. Catalog for Christie’s Hong Kong, October 30, 1995 auction.

- Christie’s (1996) Magnificent Jadeite Jewellery. Catalog for Christie’s Hong Kong, November 5, 1996 auction.

- Christie’s (1997) Magnificent Jadeite Jewellery. Catalog for Christie’s Hong Kong, April 29, 1997 auction.

- Christie’s (n.d.) 1999: Christie’s captures its largest share ever of the jewellery auction market. Christie’s press release, 6 pp.

- Cummings J., Wheeler T. (1996) Lonely Planet Travel Survival Kit: Myanmar (Burma), 6th. ed. Lonely Planet, Hawthorn, Australia, 393 pp.

- Damour A. (1863) Notice et analyse sur le jade vert: réunion de cette matière minérale à la famille des wernerites. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences, Vol. 56, pp. 861–865.

- Deer W.A., Howie R.A., Zussman J. (1963) Rock-forming Minerals. Vol. 2, Chain Silicates. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- DelRe N. (1992) Gem Trade Lab notes: Repaired jadeite. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 193–194.

- Ehrmann M.L. (1958) A new look in jade. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 9, No. 5, pp. 134–135, 158.

- Eldridge F. (1946) Wrath in Burma, 1st ed. Doubleday & Co., Garden City, NY, 320 pp.

- Fritsch E., Wu S.-T.T., Moses T., McClure S.F., Moon M. (1992) Identification of bleached and polymer-impregnated jadeite. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 176–187.

- Goette J. (n.d.) Jade Lore. Reynal & Hitchcock, New York, 321 pp.

- Griffith W. (1847) Journals of Travels in Assam, Burma, Bootan, Affghanistan, and the Neighbouring Countries. Bishop’s College Press, Calcutta, reprinted in 1971 by Ch’eng Wen Publishing Co., Taipei, 529 pp.

- Gübelin E.J. (1964–65) Maw-sit-sit: A new decorative gemstone from Burma. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 11, No. 8, pp. 227–238, 255.

- Gübelin E.J. (1965a) Jadealbit: Ein neuer Schmuckstein aus Burma. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Edelsteinkunde, No. 51, pp. 4–22.

- Gübelin E.J. (1965b) Maw-sit-sit–A new decorative gemstone from Burma. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 9, No. 10, pp. 329–344.

- Gübelin E.J. (1965c) Maw-sit-sit proves to be jade-albite. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 9, No. 11, pp. 372–379.

- Gump R. (1962) Jade: Stone of Heaven. Doubleday & Co., Garden City, NY, 260 pp.

- Hänni H.A., Meyer J. (1997) Maw-sit-sit (kosmochlore jade): A metamorphic rock with a complex composition from Myanmar (Burma). Proceedings of the 26th International Gemmological Conference, Idar-Oberstein, Germany, pp. 22–24.

- Hansford S.H. (1950) Chinese Jade Carving, 1st ed. Lund Humphries & Co., London, 145 pp.

- Harlow G.E., Olds E.P. (1987) Observations on terrestrial ureyite and ureyitic pyroxene. American Mineralogist, Vol. 72, pp. 126–136.

- Harlow G.E., Sorensen S.S. (in press) Jade: Occurrence and metasomatic origin. Extended Abstracts of the 25th International Geological Congress, August 2000, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Healy D., Yu R.M. (1983) Quality grading of jadeite. Lapidary Journal, Vol. 36, No. 10, pp. 1670–1674.

- Hertz W.A. (1912) Burma Gazetteer: Myitkyina District. Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Rangoon, Volume A, reprinted 1960, 193 pp.

- Hind Co. Map (1945) Mogaung Sheet, Hind 1095 Sheet 92C, First Edition Unlayered.

- Ho L.Y. (1996) Jadeite, English ed. Transl. by G.B. Choo, Asiapac, Singapore, 127 pp.

- Hobbs J.M. (1982) The jade enigma. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 3–19.

- Htein W., Naing A.M. (1994) Mineral and chemical compositions of jadeite jade of Myanmar. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 269–276.

- Htein W., Naing A.M. (1995) Studies on kosmochlor, jadeite and associated minerals in jade of Myanmar. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 24, No. 5, pp. 315–320.

- Hughes R.W. (1987) The plastic coating of gemstones. Australian Gemmologist, Vol. 16, No. 7, pp. 259–261.

- Hughes R.W. (1999) Burma’s jade mines: An annotated occidental history. Journal of the Geo-Literary Society, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 15–35.

- Hughes, R.W., Galibert, O. et al. (1996–97) Tracing the green line: A journey to Myanmar’s jade mines. Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone, Vol. 167, No. 11, Nov, pp. 60–65; Vol. 168, No. 1, Jan, pp. 160–166.

- Hughes R.W., Slavens C. (1999) Tales from the Crypt–GQI lab news: Jadeite–Repaired, assembled, treated. GQ Eye, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 10–11.

- Hughes, R.W. and Ward, F. (1997) Heaven and hell: The quest for jade in Upper Burma. Asia Diamonds, Vol. 1, No. 2, Sept-Oct, pp. 42–53.

- Jackson J.A., Ed. (1997) Glossary of Geology, 4th ed. American Geological Institute, Alexandria, VA, 769 pp.

- Johnson M.L., Koivula J.I., Eds. (1998) Gem news: Jadeite boulder fakes. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 141–142.

- Kammerling R.C., Koivula J.I., Johnson M.L., Eds. (1995) Gem news: Jade market in Mandalay. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 278–279.

- Kammerling R.C., McClure S.F. (1995) Gem Trade Lab notes: Jadeite jade assemblages. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 199–201.

- Keller P.C. (1990) Gemstones and Their Origins. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 144 pp.

- Koivula J.I., Kammerling R.C., Fritsch E., Eds. (1994): Gem news: Coated jadeite. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 30, No. 3, p. 199.

- Lee R. (1956) Jade cutting in Orient. The Mineralogist, Vol. 24, No. 3, March, pp. 138–140.

- Lintner B. (1994) Burma in Revolt. Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 514 pp.

- Lintner B. (1996) Land of Jade: A Journey from India through Northern Burma to China, 2nd rev. ed. White Orchid Press, Bangkok, 380 pp.

- Mével C., Kiénast J.R. (1986) Jadeite-kosmochlor solid solution and chromian sodic amphiboles in jadeitites and associated rocks from Tawmaw (Burma). Bulletin de Minéralogie, Vol. 109, pp. 617–633.

- Mining Journal Annual Review (1970) Diamonds, gemstones and abrasives: Other gemstones. Mining Journal, London, June, p. 124.

- Morimoto N., Fabries J., et al. (1988) Nomenclature of pyroxenes. American Mineralogist, Vol. 73, pp. 1123–1133.

- Myanma jade (1991) Myanma Gems Enterprise, WPD, Yangon, unpublished report.

- Ng J.Y., Root E. (1984) Jade for You: Value Guide to Fine Jewelry Jade. Jade N Gem Corp. of America, Los Angeles, CA, 107 pp.

- Noetling F. (1893) Note on the occurrence of jadeite in Upper Burma. Records, Geological Survey of India, Vol. 26, pp. 26–31.

- Ou Yang C.M. (1993) Microscopic studies of Burmese jadeite jade–1. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 23, No. 5, pp. 278–284.

- Ou Yang C.M. (1995) Jadeite Appreciation. Cosmos Books Ltd., Hong Kong, 191 pp.[in Chinese]

- Ou Yang C.M. (1999) How to make an appraisal of jadeite. Australian Gemmologist, Vol. 20, No. 5, pp. 188–192.

- Ponahlo J. (1999) Cathodoluminescence du jade. Revue de Gemmologie A.F.G., No. 137, pp. 10–16.

- Rossman G.R. (1974) Lavender jade: The optical spectrum of Fe3+ and Fe2+–Fe3+ inter-valence charge transfer in jadeite from Burma. American Mineralogist, Vol. 59, pp. 868–870.

- Soe Win (1968) The application of geology to the mining of jade. Union of Burma Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 1, pp. 445–456.

- Sorensen S.S., Harlow G.E. (1998) A cathodoluminescence (CL)-guided ion and electron microprobe tour of jadeitite chemistry and petrogenesis. Abstracts with Programs, 1998 Annual Meeting, Geological Society of America, Vol. 30, p. A-60.

- Sorensen S.S., Harlow G.E. (1999) The geochemical evolution of jadeitite-depositing fluids. Abstracts with Programs, Annual Meeting of the Geological Society of America, Vol. 31, p. A-101.

- Thin N. (1985) Petrologic-Tectonic Environment of Jade Deposits, Phakant-Tawmaw Jade Tract, Burma. Department of Geology, University of Rangoon.

- Tröger W.E. (1967) Optische Bestimmung der gesteinsbildenden Minerale. E. Schweizer-bart‘sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart, Teil 2.

- United Nations (1979) Geological Mapping and Geochemical Exploration in Mansi-Manhton, Indaw-Tigyaing, Kyindwe-Longyi, Patchaung-Yane and Yezin Areas, Burma. Mineral Exploration Burma, Technical Report 7, United Nations Development Programme, 13 pp., 6 maps in body.

- Wang C. (1994) Essence and nomenclature of jade – A problem revisited. Bulletin of the Friends of Jade, Vol. 8, pp. 55–66.

- Wills, G. (1972) Jade of the East. New York, John Weatherhill, Inc., 1st ed., 196 pp.

- Wu S.T. (1997) The identification of B + C jade. Journal of the Gemmological Association of Hong Kong, Vol. 20, pp. 27–29. (back to top)

About the Authors

George Bosshart is chief gemologist, Research and Development, at the Gübelin Gem Lab, Lucerne, Switzerland. About the Photographers Tino Hammid is Los Angeles-based gem and jewelry photographer.

|

|

|

Nephrite

has little value as a gem

in and of itself, but carvings

can be quite valuable.

Nephrite

has little value as a gem

in and of itself, but carvings

can be quite valuable.