Gem Mining in Burma

|

Gem Mining in Burma

The following article is reprinted by kind permission of Gems & Gemology, in which the original appeared, Spring 1957 (Volume IX, Number 1). Readers of Ehrmann’s unpublished manuscript, “The Ruby Mines of Mogok,” will be on perhaps overly familiar terrain, but will have the opportunity, via the images, to put faces to names, and the visual to the conceptual.

The photo on the cover at right (click to enlarge): “The oldest pagoda in Mogok. It is reputed to be located on very rich gem soil, but will never be worked because it is sacred ground.” Please note that we have removed scanning artifacts from most of the photos below, which also has softened the photos slightly.

INTRODUCTION

For many centuries, Burma has been one of the most important gem centers in the world. The Mogaung area, practically in the path of the famous World War II Burma Road, is the only commercial source of jadeite that produces qualities ranging from the finest gem emerald green to the cheapest utilitarian quality. The gem mines in Mogok are the only sources of fine gem rubies; Siam rubies are generally inferior. Only in rare cases is a fine Siam ruby found. Today, approximately eighty-five percent of all rubies and sapphires mined are of Burmese origin, especially since the Kashmir mines in India have ceased operations on any large scale.

Despite sufficient time and adequate facilities for making a complete and thorough investigation, a superficial survey in the course of several trips during the past two years revealed the presence of immense wealth still hidden within Burma. Until a complete scientific investigation is made of the gem areas in Burma, it is hoped that this article will fill the interim gap.

GEOGRAPHY

Burma, or the Union of Burma as it is now called, is divided into six states: Burma, Shan, Kashin, Kayah, Chin and Karen. It is a long, narrow country, bordered by India and Assam on the west, by Tibet and China on the north and by Siam on the east. The port of entry into Burma, either by sea or air, is Rangoon, its capital city. Rangoon has a population of about 800,000 people, consisting of approximately 550,000 Burmese, 125,000 Chinese and 125,000 Indians. All Burma has a population of 18,000,000. By contrast with India and other Asiatic countries, its people seem prosperous, wellfed and wellclothed. Slums and poverty are evident only in the large cities of Rangoon and Mandalay.

Rangoon is a rather impressive city with wide, pleasant, well-laid-out streets and many beautiful parks within the city limits. However, the ravages of World War II are still seen in the many bombed-out buildings with all their rubble. The slum sections, too, are as bad as anywhere in India, with crowds and filth evident everywhere.

|

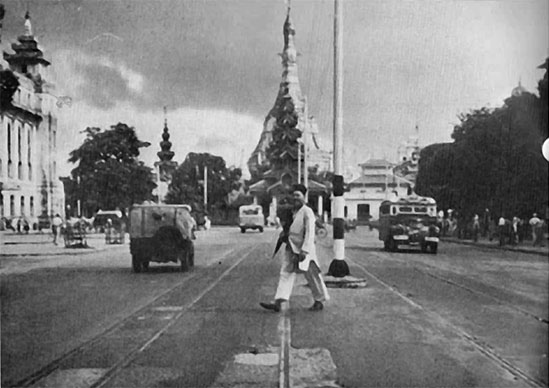

| Sula Pagoda, on the Sula Pagoda Road, in the heart of Rangoon. |

The residential section of the city is well kept with many beautiful mansions standing majestically on Prome Road, the finest residential street in the city. There are many temples and pagodas of beautiful architecture (though not as elaborate as those in Siam). The Sula Pagoda, in the center of the city, has a tower over fifty feet high covered with 24-karat gold leaf to which gold is added regularly every few years. This gold is reputed to be worth many millions of dollars. The Shwedagon Pagoda is located in the residential area on a lovely landscaped two-mile square. This pagoda, with its golden spire glittering in the sunlight is the largest and finest Buddhist temple in the world; it, too, is worth millions of dollars.

Another interesting landmark is the University of Rangoon, known as the finest higher education institution in the Far East. It consists of many buildings on a huge campus, with a mixture of old and modern architecture. It is staffed by a fine, international faculty.

Transportation within Burma is poor. There is a railroad from Rangoon to the north, but it is old, dilapidated, and very slow. A trip to Mandalay, a distance of 450 miles, takes about three days and is extremely dangerous. Each train leaving Rangoon is preceded by an armored car with a complement of soldiers, since these trains are frequently attacked by marauding bands of insurgents roaming the jungles of Burma. Even this protection does not prevent frequent attacks and much loss of life. Another mode of transportation is by slow, crowded, and uncomfortable river boats on the Irrawaddy River, the most important river in Burma and navigable for about 1000 miles. Such a trip is a combination of three days of train travel to Mandalay, two days by boat to Thabeikian, and sixty miles by automobile to Mogok.

|

| Burmese plane and crew that flew author from Rangoon to Mogok. |

However, it is air travel that offers the finest mode of transportation within Burma. The Union of Burma Airlines is most efficient, flying regularly to all points north. The planes used are Dakotas and DC3s, flown by Burmese pilots trained in England. These two-motor planes are found best for the short distances flown. There are two daily flights to Mandalay and flights once a week to the capitals of all other states, thus making air travel the only efficient way to get to Mogok. A plane leaves Rangoon every Friday at 8:00 A.M. and arrives in Momeik about noon, where it is met by a jeep for the twenty-eight-mile drive to Mogok. This brief jeep trip is usually accompanied by an element of danger, since the roads are frequently mined by the insurgents who roam the jungles. Cars are frequently robbed or blown up. The insurgents are political enemies of the state. In addition, there is the ever-present danger of the highway bandits who steal everything of value but seldom kill.

Nevertheless, the drive to Mogok is fascinating. Momeik is 800 feet above sea level and Mogok is 4000 feet above, so there is a continual climb through extraordinarily interesting country. Scenically, it is the most astounding country in all Asia. Occasionally, green valleys appear through thick jungles; then, suddenly, terrible desolation and ruined pagodas come into view. Here and there is a village beyond which are picturesque rice paddies. The roads are deteriorated and appear to have had no care in years.

Mogok is situated in a magnificent valley, surrounded by majestic mountains which are studded with temples and pagodas, some very modern and others thousands of years old. Geographically, Mogok is considered a part of the Burma State, although it is actually located in the western part of the Shan State. This fact dates back a long time, before the English occupation of Burma. Burma was a kingdom then, and all of Burma was ruled by Burmese kings. Because of the vast wealth in the Mogok area, these kings retained their hold on it and fought the Sab Bwas (same as maharajas of India) who tried to wrest it from them.

Even under British rule, the Mogok area was kept as a separate entity, as an independent state. A British commissioner was appointed for this area alone. Until Burma became a republic, uniting all six states, only the State of Burma was actually the Kingdom of Burma. The other five states were ruled by Sab Bwas. These Sab Bwas are still very powerful politically, all holding ministerial rank. As Sab Bwa of his own state, he is the minister representing his state in the Union Government. In addition, he may, and usually does, hold another political office.

The Mogok valley is about twenty miles long and two miles wide. In the center of the village of Mogok is located a beautiful lake, created by digging for precious stones during the Ruby Syndicate era. The Mogok gem area reaches to the city of Momeik, a distance of twenty-eight miles to the north and sixty miles to the west, up to the villages of Twingwe and Thabeikian on the Irrawaddy River.

Mogok has a moderate climate. During winter, the maximum temperature is 25 degrees during the night and early morning. During the day, it rises to 70 degrees. In summer, the evenings are not very cold and the maximum day temperature is about 95 degrees. It is a heavy rainfall area, ranging from ninety inches of rain to one hundred and thirty-five inches in the rainy, or monsoon, season from May to November.

The chief industries of Burma are the cultivation of rice and the logging of timber, mainly teakwood. Both commodities are exported to many countries, accounting for Burma’s only sources of foreign exchange. Mogok is the exception. The only industry in the entire area of Mogok is the mining of gemstones. There is hardly any cultivation in this area; consequently, even rice, which is the staple food, has to be brought in from Momeik.

In addition to the temples and pagodas one sees in the mountains, there are various plants of gorgeous colors; brightly colored blooming magnolia trees and cherry blossoms are abundant. One shrub, similar to rhododendron, grows all over the mountains. The natives are superstitious about these rhododendron shrubs, believing that they are created by the good spirits hovering in the area and called “the gods of the mountain.”

Wild life is also abundant. Many varieties of birds can be seen almost any time of day. Elephants, tigers, and diverse species of the deer family thrive in the mountains and nearby jungles.

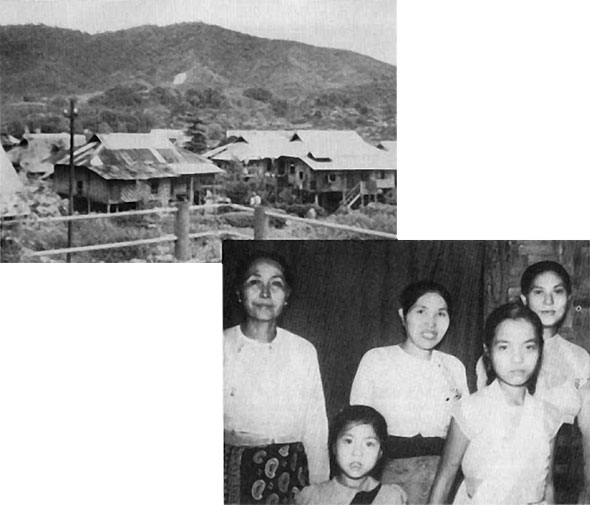

PEOPLE

The Burmese are a friendly, smiling people. Their dress is neater and more beautiful than anywhere else in the Orient. Both men and women wear skirts, or longhis, and both sexes delight in bright colors and silk attire. A longhi is a skirtlike garment. Cotton longhis are used for daily wear; silk longhis are worn on holidays and for special occasions. The longhis are very wide to give plenty of room to the wearer. They are stepped into and are folded and knotted in front. It is not unusual to see a man or woman open the longhi while walking, shake it with graceful motions and retie the knot, all in the twinkling of an eye. These movements are done unconsciously and with mechanical precision. Nowhere in the world do people take more pride in their wonderful, bright, harmonious colors. The men generally wear sport shirts with their longhis; the women wear sheer, white blouses adorned with ruby- or sapphire-set gold buttons. Unlike the rigid customs in India, the life of the Burmese is free from the effects of any caste system and seclusion of women, which may account for their pride in gay dress. In the interior, even though less civilized, the people of the various tribes have their distinctive and picturesque modes of dress and adornment.

|

| Above, typical huts in the mining village of Mogok. Below, family in Mogok with which author stayed, showing typical Burmese dress. |

In the section of Burma which borders on Assam, Tibet, Yunan Province of China, and French Indo-China live the peaceful Shans, the warring Kachina and the headhunting Nagas. These people have their own unique and colorful dress. The women wear large turban-type hats made of gay materials. In their noses, they wear a gold drop which is fastened to the center of the nostril and hangs down below the mouth—a most awkward place, indeed, for a pendant! But in every part of Burma, all the Burmese have one thing in common: a fierce pride in their newly gained independence and freedom from English rule since 1948.

U Khin Maung, my agent and interpreter, had made arrangements for us to stay at his parents’ home, a typical Mogok hut built on a concrete slab with woven bamboo walls and native wooden beams. Upon our arrival, we were given a fine welcome by his parents, two younger brothers and a sister. I was given a cot in the corner of the livingroom. In all the homes in Mogok, the livingrooms serve a dual purpose, since they are also the family’s shrine. In one corner, a pagoda occupies the most prominent place in the room. In front of it is a table on which are placed flowers and bowls of rice, changed daily as offerings to Buddha. Daily prayers, in a prone position, are said to Buddha morning and night. According to the Buddhist religion, no one can enter a pagoda wearing shoes, so everyone takes off his shoes before entering the livingroom of any house in Burma.

|

| A livingroom of one of the prominent gem dealers, showing a centerpiece of an altar consisting of peridot pagoda, peridot buddha and a quartz crystal buddha. (Photo courtesy of Edward R. Swoboda) |

All homes in Mogok have another thing in common: the complete lack of any sanitary facilities. Outhouses are found in the rear of the huts. Water for washing and cooking is brought in from pumps, sometimes found in the rear but more frequently in front of the huts. Baths are taken at these pumps in full view of the entire population. Both men and women manage their longhis so gracefully that the dry one is on before the wet one is completely off. My first attempt at bathing in the street almost turned into a fiasco, because I wasn’t quick enough in changing from the wet to the dry longhi. Although no one was visible at the moment, I heard much laughter from my invisible audience. After practicing several times, I also became adept in the rapid change of garments.

Our first evening in Mogok, we retired early after a typical Burmese dinner. We ate a tasteless, thin soup containing mustardlike greens, followed by white rice in curry sauce with bits of pork, and other vegetables and tea. About 6:00 A.M., I was awakened by the morning prayers of all our neighbors. We had our breakfast of two boiled eggs, bread and butter and coffee. We had brought canned butter and instant coffee with us. We started our tour of the town with a courtesy call to the S.D.O. (subdivisional officer), who acts as mayor, chief of police, fire chief and magistrate, as well as chief mining inspector. His name is U Hla Tint, a charming and personable young man of about thirty. He is respected by all the twenty thousand inhabitants of the area. He gave us a most cordial welcome and promised to give us advice and help in any way we wished. After the customary cup of coffee, followed by a cup of tea, we departed, assured that we would have all the cooperation we needed from the law in Mogok.

|

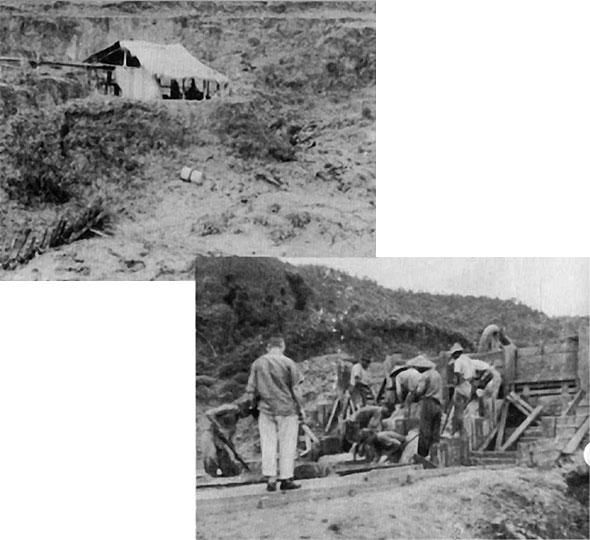

| Mogok gem mine after fifteen feet of sand layer has been removed to bare the gem gravel. |

We visited a number of the most important mine owners and dealers, from whom I gathered much essential information. The, procedure in visiting these people was invariably the same: the minute we arrived, shed our shoes and sat down in a squatting position, cups of coffee were served. This coffee was unlike any I had ever tasted. Apparently, the coffee, milk, sugar and water are cooked together and the sugar was plentiful. It had a sickening sweet taste, but we finished it and were immediately offered cups of tea, which tasted good after the first awful concoction. The number of cups of coffee and tea we imbibed each day depended on the number of visits we made. A sincere feeling of welcome everywhere we went made me feel at home.

MINING AND GEOLOGY

The Mogok area is the only place in the world that has a population of about twenty thousand people who make a living from gemstones. Except for diamonds and pearls, almost every variety of gemstones, both precious and semi-precious, has been found there. The total gem area is approximately 1916 square miles. Gem deposits are found within an eight-mile radius of Mogok, and there are about twelve hundred individually owned mines operating in the area.

The village of Mogok is totally dissimilar from Idar-Oberstein, Germany, in people and architecture, but they are very much alike in the predominance of the stone industry. As in Idar-Oberstein, every house in Mogok is a lapidary shop. However, Idar-Oberstein is only a gem-cutting center; in the immediate vicinity of Mogok are many gem mines.

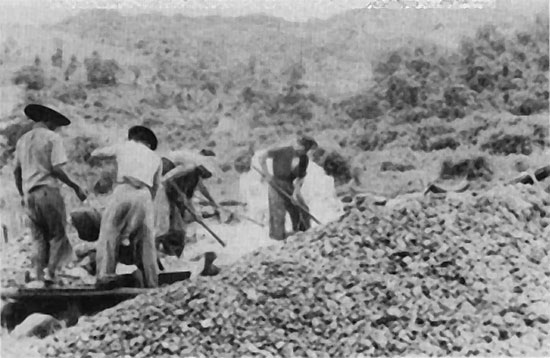

There are two types of mining operations. After an area has been discovered where signs of gemstones are present, the top layer of sand, sometimes as deep as fifteen feet, is removed. When the gem gravels become visible, the real work begins. Depending on the size of the area, from three to twenty-five miners begin to loosen the gem gravels, the large boulders being discarded on the sides. The smaller gravels are gradually shoved to a pile in a convenient corner by shovels and picks. In most mines around Mogok where water is plentiful, a centrifugal pumping system is used to pump the gravels up to a high point with an eight-inch pipe. A wooden structure receives all the gravels, since it can hold from thirty to forty tons. At a specified time of day, the gravels are washed in the following manner. The miners that loosened the gravels come into the structure and remove the largest pebbles by hand. The balance is pushed through a wire mesh to the first level, then to the second level, and finally to the bottom. Thus, the large pieces are held on the first level, smaller pieces on the second, and the smallest on the third, or bottom level.

|

| Above, hut housing pumping gear in Ruby Mine. Below, wooden structure into which gem gravels have been raised by centrifugal pumps. |

At this point, the washing operations actually begin. This is a top-secret operation; only the mine owner and his miners are present during this final step. No one is supposed to learn what luck the mine had on any day!

|

| Above, first washing of heavy gravel. Below, moving gem gravels to the lowest level before final washing. |

|

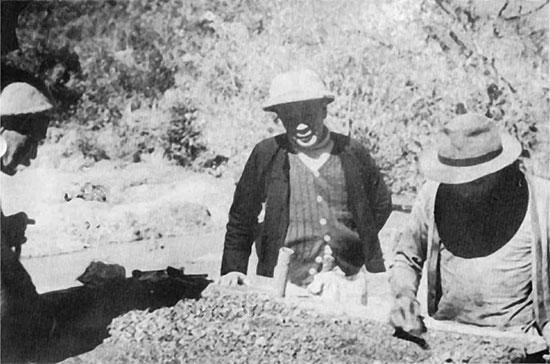

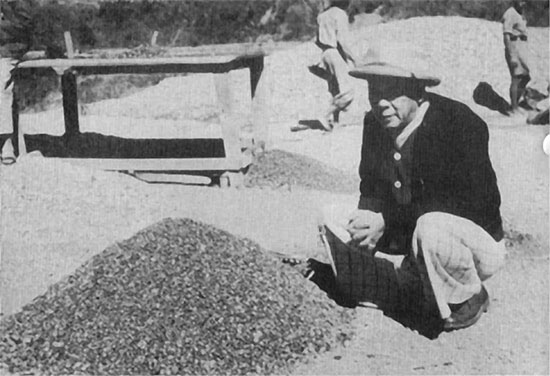

The gravels on the lowest level are then taken out in wire baskets and thoroughly washed again. Many pebbles are removed by hand and the balance is carried by each miner to a picking table four by eight feet in size. The mine owner and his assistant stand there moving the gravels with a metal blade in one hand; the other hand is used to pick out all gems, which are then placed in a bamboo container while the other gravels are pushed off the table. Such gravels still contain small pieces of rubies, sapphires and other gems with which the mine owner does not think it worth while to bother. This material is gathered into piles which are sold to the poor women relatives of the mine owner. After purchasing one or two piles for a very small amount of money, these women comb them for all remaining gems. If, by some chance, the mine owner has overlooked a large gem, it rightfully belongs to the woman purchaser of the pile in which it is found. Naturally, the results of any washing can be joyous or very disappointing. The entire operation is a rapid one, and the results are quickly seen.

|

| Above, final washing of gem gravels before removal to the picking table. Below, assorting gems from gravel on picking table. |

|

|

| Above, picking table, showing bamboo container for selected gems. Below, poor women-relatives sorting reject lots of gravels for any remaining small gems. |

|

The other method is to dig square wells to depths of twenty-five to thirty feet. To prevent the walls from caving in, the miners shore them with bamboo rods. After a hole is secure, the mining process begins. The gem gravels are brought to the surface in rattan baskets raised by a rope, a process similar to drawing water from a well. The gravels are then washed and the precious stones removed.

|

| Wealthy mine owner with pile of gravel in which an important sapphire was found. |

Rubies and associated minerals such as spinels are formed in a matrix of white, dolomitic, granular limestone. These rocks have been altered by contact with molten, igneous material which recrystallized the calcium carbonate as pure calcite, while the impurities became the rubies, spinels and other minerals. Rubies now are seldom found in this matrix. All mining is in the adjacent alluvial ground.

The origin of the Mogok gem area has not been described anywhere, as there has been no scientific investigation made to date. My own superficial observations indicate that there are at least two hundred and fifty mineral species within the area. It is safe to say that the Mogok-area gems are of metamorphic origin. The original rock in which these gems were formed disintegrated on the earth’s surface. Loose, disintegrated soil was formed in which the gem minerals, such as rubies, sapphires and spinels (which are not harmed by water and other atmospheric conditions), were imbedded and remained in excellent condition. This disintegration was washed away by waters and the gems were washed along as well. Eventually, the waters stopped flowing and the gravels remained, covered by sand layers of from five to fifteen feet, where they are now waiting to be discovered. New areas are opened daily where new finds are continually being made. Rubies are known to occur in three important tracts in Upper Burma, but the original source of the gems is found to be highly crystalline limestone.

The variety of minerals found in these mines varies a great deal. Statistics are difficult to obtain because of the previously mentioned secrecy that prevails. I did, however, obtain the cooperation of one mine owner in this respect, a jovial Burman, U Nyunt Maung, one-man owner of the largest mine in the Mogok area. According to him, about seventy thousand carats of rubies and sapphires are mined there yearly. Of unusual interest is the fact that only one per cent of spinels come from this mine. These rubies and sapphires are not all of gem quality. A good guess would be that less than five percent of the seventy thousand carats is of decent quality; only one-half of one percent is of gem quality. Other varieties of gemstones found here are danburite, scapolite, beryl, zircon, amethyst and fibrolite. In addition, many varieties of iron minerals and rare earths occur, such as monozite, ilmenite, columbite and tantalite.

In Kathe and Kyatpyin (the first six miles and the latter eight miles from Mogok), in addition to individually owned mines employing from five to fifty miners, there are also large tracts of land leased to individual miners who work a few feet of the area by the hole-digging method previously described. As this area is rather dry, most of the gem gravels are piled up in huge piles and washed during the months of the rainy season. Although not considered a rich area, it still provides about one-half million dollars worth of rubies and sapphires annually.

Most mine owners and miners are interested only in the precious rubies, sapphires and spinels because of the ready market for them; consequently, the other gems are sadly neglected. If it were not for the fact that Mr. A. C. D. Pain, a very competent gemologist, who has been living in Mogok for many years, has shown a constant interest in the rarer gems, they would have been ignored as worthless. The following gemstones are found in almost all the Mogok area: peridots, which will be described more fully later; fine, yellow danburites, up to forty carats; scapolite cat’s-eyes in white, pink and blue of various sizes up to fifty carats; apatites in blue and green, as well as the chatoyant variety, which is rather common; an abundance of albite cat’s-eyes up to fifty carats; topazes; and orthoclases and other varieties of the feldspars. Less abundant minerals in the same area are kornerupines, sphenes, diopsides, iolites, chrysoberyls, zircons, and, occasionally, a new gem mineral. Mr. Pain has recently found a new species which is now being described by the British Museum of Natural History in London.

Mr. Pain owns a magnificent collection of representative Burmese gems which he is continually improving in quality. When I saw it last, it contained some 250 gems varying in size from two to 150 carats. The outstanding stones are a blue kornerupine weighing about twenty carats, a sphene of similar size, a pink scapolite cat’s-eye of about twenty carats in weight, and a fibrolite of most unusual size. Unfortunately, all my efforts in trying to purchase this collection failed.

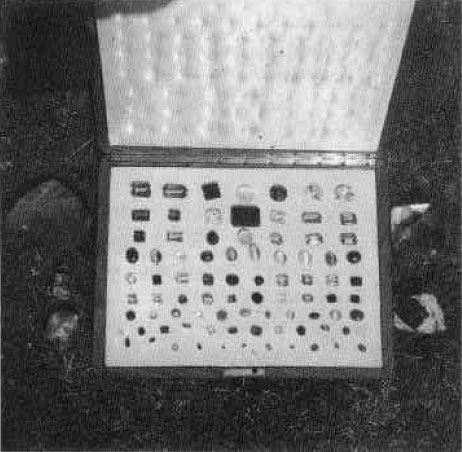

|

| Fabulous gem collection of Mr. A. C. D. Pain consisting exclusively of Mogok gems. (Photo courtesy of Edward R. Swoboda) |

In Sakhangy, twelve miles southwest of Mogok, quartz and topaz crystals are found in highly decomposed pegmatite. Because of excessively heavy rains in the past few years, this deposit has caved in completely. The topazes are of various colors and well crystallized, not unlike those found in Brazil. However, the fine golden colors desirable for jewelry purposes are rare.

For a long time, peridots of commercial gem quality were believed to have come only from St. Johns Island in the Red Sea. However, there is a more important locality for this beautiful gem mineral in a village called Pyaung Gaung, which is eight miles northwest of Mogok. The natives call these peridots Pyaung Gaung zain (zain means stone). No investigation could be made there since this territory is completely in the hands of insurgents. Several unusually fine, large specimens of these crystallized peridots were purchased and are now in some of our museum collections. The quality of the Burmese peridots is similar to that found in the Red Sea, but the largest stones of pure gem quality come from Burma.

In addition to rubies and sapphires, other important gem minerals mined in Burma include jadeite. Burma is just about the only source of jadeite in the world. This gem mineral deserves its own chapter later.

Burma is also rich in strategic minerals. The tin mines of the Tennarim Peninsula are very important. This peninsula is in the southern-most part of Burma and has a coastline of about one thousand miles, connecting in the south with the Malay Peninsula. Tungsten is also mined in large quantities on the Tennarim Peninsula.

In the central and northern part of Burma are many deposits of tin, tungsten, lead, silver and copper, which are suitable for mining. Because of lack of transportation, difficult terrain, and insurgent activities, development of these mines has been most inadequate. There are also a few rich oilfields in the central part, providing sufficient gasoline for Burmese consumption.

Other Burmese minerals worth mentioning are antimony, asbestos, barite, bismuth, chromite, gypsum, graphite, manganese, molybdenum and monazite. There are visible signs that all these deposits are being presently surveyed by private and government geologists, evidencing a purposeful movement to develop all the natural resources of Burma.

HISTORY

It is difficult to ascertain exactly when Mogok was founded. That it was first settled by man about 3000 B.C. is indicated by relics of this period used by the Mongolians, who were the first settlers. Such relics consisted of stone axes, chisels, and many types of spears and stone arrowheads similar to our Indian ones.

Modern Mogok was founded in 579 A.D., when it was all jungles and thick forests. While hunting in the jungles, headhunters of the Sab Bwa of Momeik lost their way and slept under a tree. At daybreak, they heard birds singing and hovering over them. Investigating the commotion of the birds, they ran into a mountain break full of beautiful rubies. They collected as many as they could carry and brought them to the Sab Bwa of Momeik. He immediately realized the wealth of the area and sent some of his household to establish Mogok. It was first called Thahpainpin Pomegranate for the fruit growing abundantly there, and such a little village still exists on the extreme west limits of Mogok.

In those days, Burma was ruled by a king named Avaking. The capital was the city of Ava, near the present site of Mandalay. After hearing about the fabulous wealth, the king started to invade the area. Then the Sab Bwa of Momeik made an agreement with King Avaking, establishing Mogok as part of Burma, in return for twelve specified villages. It is on record that in 1254, a pact was signed by King Ava and the Sab Bwa of Momeik settling all their differences. The Mogok area was now a part of the Burma Kingdom and gem trading began. History has it that no mining operations were first required, since the gems were found everywhere.

According to a legend, an agent of King Mindon, named U Tun Po Hland, showed a ruby called the Ngamauk Ruby to a French trade mission, telling them that quantities of such valuable stones were to be found in Mogok. At that time, France controlled Siam and now wanted to purchase the whole Mogok area from King Mindon. The members of the trade mission were especially impressed when the Ngamauk Ruby was placed in a pan of water and the water turned red, the color of the ruby. King Mindon flatly refused to sell, saying there was not enough money in the world to buy the fabulous area. The ruby itself is said to have become part of the famous British Crown Jewels. Although there was no description given as to weight, subsequent accounts made it a very large stone and probably the famous one in the crown jewel collection that was tested a few years ago and found to be a spinel.

In 1886, the British Government occupied Burma. After a victorious battle in the Mogok area, Major Charles Barnard and his troops took over. Barnard Village, where peridots are found, is still in existence. On March 29, 1888, the area was formed as the Mogok Ruby Mines District, and Mr. G. M. S. Carter became its first administrator. Distinct from other areas, it was ruled as a separate entity and controlled solely by the British. Mr. A. R. Godbar was the last administrator in 1920.

In 1889, the Ruby Mine Company Syndicate, Ltd., was formed, capitalized by numerous English bankers and industrialists. It was handled by the management firm of Streeter and Company in London. According to agreement, this company paid the British Crown forty thousand rupees yearly plus one-sixth of all profits accumulated. Barrington Brow, M. P., was sent from England to negotiate the first five-year contract, which expired in 1895.

Scientific mining began and several geologists were sent to survey the Mogok area. They reported that the bulk of the gembearing gravel was located in the center of town where most of the natives lived. The company negotiated with the owners of these properties and bought all the huts located in the surveyed gem-bearing beds. The natives were given new homes or, where possible, old homes were moved to new locations hacked out in nearby jungles. These moves presented no problems, since the natives were well compensated and were promised employment.

Mining began immediately after the people were moved. Electricity was brought to Mogok with the construction of a power plant. Digging began and several millions of dollars worth of rubies, sapphires, spinels and other gems were mined. A single ruby of fabulous size, purportedly worth $100,000 (a lot of money in those days), was discovered. Profits were good for the first contract. The company and townspeople were happy with the new way of life.

As the contract had expired, in 1896 the company negotiated again with the British Government and agreed to pay a tax of 3,150,000 kyats (about $800,000) plus one-fifth of the total profits for fourteen years. This contract included all the mines within a radius of ten miles of Mogok. Those were the boom days with everyone working and much money in circulation.

In 1906, the company extended its mining operations to other areas and bought all the property in the city limits of Mogok, again moving homes to new sites. The original Mogok area is today the site of a beautiful lake in the center of town. Also, about 1906, a 42-carat fine pigeon-blood ruby was found. After cutting, the ruby, weighing twenty-two carats, was purchased by an Indian gem dealer, M. Chodilla, for 300,000 kyats (over $100,000).

Because of heavy rainfall and much excavating, pumping became a serious problem. The hole would fill and stop all mining operations during the rainy season. Experts from London solved the water problem by building tunnels for the water to flow off from the hole; however, this proved to be only a temporary solution. Tunnels costing $200,000 were built into the mountains but after a year the same problem arose.

In 1914, affairs of the company began changing rapidly for the worse. Because of stealing, technical problems and wide extensions, large sums of money were lost. Operations were continued, however, until 1922, the expiration date of the contract, marking cessation of company operation. Some personnel remained until 1928, working privately with local people on a half-share basis. On August 28, 1928, this group attempted to remove the water from big tunnels in order to empty the big hole. That venture culminated in disaster as the mountain side caved in; nevertheless, gem mining continued.

Before the beginning of World War I, an Englishman named Albert Ramsay settled in Mogok as a lapidary and dealt in rough gems. His alert and inventive mind eventually made him the savior of the mining industry in Mogok. In previous years, only the clear rubies, sapphires and spinels had been sought. Such stones were not too plentiful, especially those of faceting quality. Mr. Ramsay began experimenting with translucent varieties of rubies and sapphires and found that by cutting certain of these crystals with the base perpendicular to the crystal axis, a star was formed. Heretofore, such material had been ignored as having no market value. After his discovery of the star, Mr. Ramsay began buying all the material he could obtain and cut it into cabochons showing wonderful stars. It took him a long time to convince the jewelers of Europe and America that this type of stone would gain favor with the gem-loving public, but he finally succeeded and mining was revived in Mogok. Mr. Ramsay also continued in the rough-gem business and in May, 1929, purchased a gem sapphire weighing 1029 carats for $30,000. Thirty-two pieces were cut from it, one of which brought the total amount paid for the original stone.

Because of pressure brought by the local people, new rules and regulations were made in 1950 when homesteading of mines began. Claims were made by individuals and granted by the Crown. The tax levy was 10 rupees per miner employed. By this time, all company holdings had been abolished and the machinery and electric plant were sold to a Mr. Morgan and a Mr. Nicols. Mr. Morgan has since died, but Mr. Nichols still carries on, supplying electricity to the whole area. Secrecy surrounding all operations makes it impossible to determine the total output of gems.

On May 7th, 1942, Mogok was invaded by the Japanese and all mining stopped. Miners dug holes in their backyards and under their homes and discovered many gems. On March 15, 1945, the British army moved in and the Japanese withdrew. The independence of Burma from British rule was declared on January 5, 1948. Mining continues in the same primitive manner, but about 1200 mines are now owned individually. Some are just two- to three-man operations, whereas others employ as many as fifty men. All miners are shareholders and split the profits with the owners, thus largely eliminating high grading.

JADE AND AMBER MINES

Both jade and amber occur in the northernmost part of Upper Burma, reached by a once-a-week flight from Rangoon to Myitkyina. This village is in the eastern part of the so-called jade and amber belt and is very near the border of Yunan Province of China. Mogaung, about fifty miles to the northwest of Myitkyina, is the last city in Burma with a railroad station. The center of the jade- and amber-mining district is the village of Mogaung, where the largest deposits are found within a radius of seventy-five miles in all directions.

The jade mines of northern Burma contain the most important deposits of this interesting material in the world. The early Chinese prized it greatly and are said to have believed that jade possessed magical qualities which made it a sacred stone. Three thousand years ago, jade from this area was brought via the caravan route to the center of China. Members of the Imperial Family and the nobility of the Chou Dynasty wore ornaments of delicately carved jade. Weapons of war such as swords, sabers, spears and knives were also fashioned from this precious stone. Jade was even buried with the dead in the belief that it would ward off evil spirits. It is no wonder, then, that all the jade mined in this area found its way to China. At a later date, its wonderful qualities, such as color and durability, became known in the Western Hemisphere and the demand increased greatly.

The jadeite region is almost inaccessible most of the year. During the monsoon season, it is practically impossible to reach, since it is a highly dissected upland region consisting of ranges of mountains which form the Chindwin-Irrawaddy Watershed. It is higher in the north than in the south and Tawman, one of the principal jade-mining districts, is situated on a plateau about three thousand feet above sea level. The highest mountain is Loimye, about a mile above sea level. Tawman is about sixty-five miles from Mogaung. There is a road which is barely passable even under the best conditions, so the most satisfactory mode of transportation, if not the fastest, is by mule truck. These conditions are serious handicaps in any attempt to complete a geological survey of the area.

Jade mining progresses for only three months of the year, from March to May. All mining activities cease with the coming of the rainy season, since the shafts fill with water within a few days.

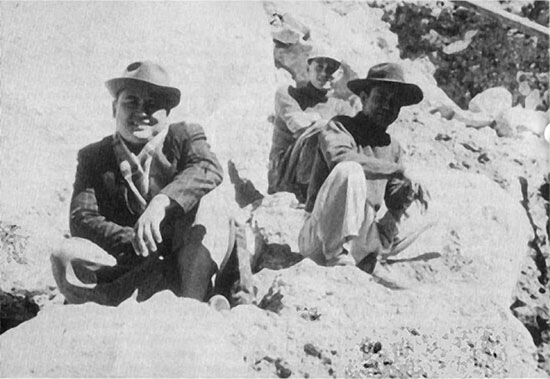

|

| Typical jade mine, with owner and two friends, in the Mogaung district of Burma. |

Many workings were observed by the author, who considered them all of similar nature. At the top, there is a very thick overburden of red earth, probably the weathering of serpentinized peridotites that form the rock into which the jadeite albite mass is intrusive. Below the serpentinized peridotites lies a thin, earthy, very light chlorite schist locally called “byindone.” Below it is an amphibole schist, or amphibolite. Next to that is an amphibole-albitite rock which is underlain by albitite and it, in turn, is underlain by jadeite.

The mining methods today are still the same as those used a thousand years ago, except that hydraulic drills are now being used in some areas. Before any jade mining is begun, every worker, whether Kachin, Shan, Burman or Chinese, prays to the jade spirits, or Nats, in the belief that they will discover valuable jade quickly if the Nats are pleased. Generally, the overburden is quarried with picks and crowbars until a steep face is obtained. Water is dammed upstream to make it flow over the steep face, washing away all earth and leaving the boulders clearly exposed for examination. It is well to remember that the selection of the locality and all the work are started through pure instinct, an inner conviction of the miners rather than any scientific reasoning. When valuable jade is discovered in one spot, all the miners flock to it and work it until all the jade has been removed. Consequently, they frequently forget where they had worked last and begin digging in spots previously mined, with much labor thus lost. Scientific mapping and a coordinated, well organized mining program would certainly yield large amounts of fine jade in this area at a small percentage of the present cost to the jade merchants, who do almost all the financing.

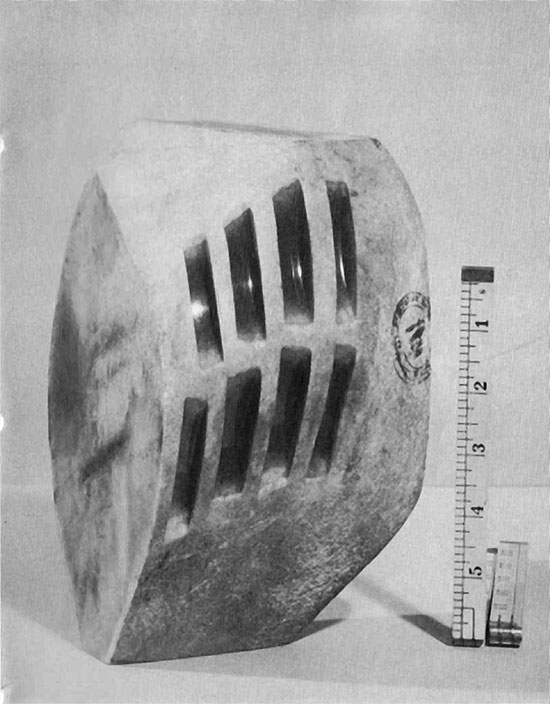

|

| Above, typical boulder of rough jade, just removed from mine, and stamped by officials. Below, rough jade, showing texture. (Photos courtesy of Wen Ti Chang, Los Angeles) |

|

There is a valuation committee in every jade mine. When a piece of jade is found, the financier has it evaluated by this committee, which receives a fee of five percent of the value. As a rule, such valuations are very low. If the financier decides to keep the jade, the miners receive half of the evaluated price. Ten percent more goes to the local government under whose jurisdiction the stone is found. Values and evaluations are never mentioned but merely indicated among the interested parties by the conventional finger pressures under a handkerchief. It is costly to ship the jade boulders to Mogaung, the chief trading center. Sometimes, as many as fifty coolies are employed to transport a boulder weighing a ton. They proceed very slowly through the rugged terrain until they reach a place where the jade can be placed in an oxcart and brought Mogaung. There, the Government again collects thirty-three and a third percent of the value before the merchant is permitted to ship his jade out of Burma.

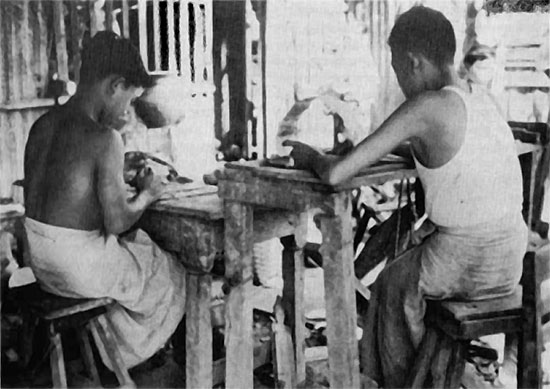

|

| Cutting jade cabochons in Mandalay, Burma. Note foot-driven pedal and carborundum plate on which cabochons are preformed. (Photos courtesy of Edward R. Swoboda) |

|

Up to this point, the value is merely a fictitious figure without any actual basis. The main thought is to have as low an evaluation as possible until all government taxes are paid. Then, the jades are prepared for local auctions and for export in the following manner: Each boulder is weighed and a seal is placed upon it. At strategic points, cuts of approximately three-fourths inch in width and one-half inch in depth are made in each boulder and polished to show the color. The Chinese jade dealers pride themselves on being able to determine the value of each jade boulder by the appearance of the polished cut. On certain days, auction sales are held for the prospective purchasers.

The auctions differ greatly from ours, since there is no audible competitive bidding. The purchaser accompanies the auctioneer along the path on which the boulders are displayed. A stop is made before each numbered boulder in which the purchaser expresses interest. With his hand and the auctioneer’s hand covered by a cloth, the bidder makes his offer by pressure on the auctioneer’s fingers, thus insuring absolute secrecy in each transaction. In the evening, the sales are completed and the boulders turned over to the highest bidders.

It is not unusual for many boulders to remain unsold during these auctions. They are then shipped to dealers in Hong Kong for similar auction sales. From a scientific point of view, it is a real gamble to buy jade in this manner. The purchasers are actually gamblers rather than jade experts. Much money has been lost by these superficial methods of purchasing.

All jades leaving Burma are shipped from Mogaung after clearance by the Government agency. Boulders of jadeite are wrapped in a heavy, dark sailcloth tied with hemp rope and shipped by Irrawaddy River boats to Rangoon, where they are put on boats going to Hong Kong. Also, a considerable quantity is smuggled across the border to Yunan, Communist-controlled China, by mules. Prior to the Communist occupation of China, jade was shipped to Canton, Shanghai and Peiping. Approximately fifteen percent of all jades, the poorest quality, remains in Burma and is usually sold in Mandalay, where there are many jade cutters and jewelry manufacturers.

Burmese amber was highly prized by the Chinese even before the beginning of the Christian era. Burmese amber is very different from amber extracted in the Baltic Sea in East Prussia. The Burmese type is a golden color with a beautiful bluish streak through it and is strongly fluorescent even in ordinary sunlight. It is also purer, harder, and tougher than the Prussian amber, thus making it excellent material for cutting and carving into figures, snuff bottles, vases and various Chinese carved objets d’art. The only other occurrence of amber of similar quality is in Sicily; this amber possesses the same fluorescent phenomenon.

Amber occurs in the lower tertiaries, which consist of finely bedded dark schists, blue shale and sandstone, the shales being generally predominant. In some places, the two are alternately interbedded with a few layers of limestone conglomerate. Sometimes, sandstone of various shades of blue and pink are almost laminated, and in places contain shaly concretions which vary in diameter from one to several inches. Generally, the sandstone and shale bear carbonaceous impressions; sometimes, these rocks contain very thin coal seams in which amber is imbedded in the form of concretions. Because of the soft nature of the shale and sandstone, few good exposures are seen on the surface.

Amber mines are located in the northernmost section of Burma and extend in a straight line to the border of Assam, through Myitkyina to the Yunan border. Hukawang Valley, comprising the villages of Maingkwan and Komaung, is the chief source. In most mines, amber occurs in pockets embedded in blue sandstone or dark-blue shale with a fine coal seam. The presence of coal seams is a favorable sign for the occurrence of good amber. Amber usually occurs in elliptical pieces and occasionally in blocklike forms. The best amber is found at a depth of about thirty-five to fifty feet, very seldom in large blocks, the average size being that of a normal closed fist.

The method of mining amber is as primitive as that of mining jade. The mine is a well-like affair about four feet square and descends to a maximum depth of approximately fifty feet. Four miners work in each pit. Two dig underground with a hoe. The other two haul up the mass in a rattan basket with a long hooked bamboo rod and examine each basket for amber. The pits are lined with a bamboo barricade which appears flimsily constructed but does hold the pit without caving in. It seemed like a miracle to the author, since there are many pits close together.

The progress in a pit is very slow; usually two men dig about two feet in a day. All mining is stopped when a hard layer of sand is reached, since the miners believe there is no amber beneath the sand. It might prove interesting to sink a few bores much deeper to test their theory. Much of the amber thus mined remains in the area and is made into earrings, bracelets and other popular jewelry worn by the natives of the Hukawang Valley. Chinese merchants, too, purchase great quantities of amber, especially the larger pieces which are suitable for carved objects d’art. They export these pieces to China where most of the carving is done. Some of this amber also finds its way to the European market.

GEM TRADING

Traditionally, the gem dealers of India are the most important in the Orient. Perhaps the widespread impression that rubies and sapphires originate in India stems from the fact that the bulk of gemstones found in Ceylon, Siam and Burma is purchased by Indian dealers who keep in close touch with the gem-producing mines. There they have informants from whom the dealers purchase information about new discoveries of gems. Because so many engage in gem trading, competition is very keen. Besides the India markets, they also supply the Western markets via Paris, where many gem-buying offices are located. Purchasers from all over the world generally find it much more convenient to do their buying in Paris, where the Indian dealers keep their outlets well supplied.

During the height of Britain’s power in India, the maharajas were the wealthy, chosen few who were able to buy the expensive gems. Each one tried to outdo the others in acquiring important gems, just as art collectors do in Europe and the United States. Consequently, for a long period of time, few large gems reached the Western markets.

|

| Author’s agent, U Khin Maung, with assorted gem gravel. (Photo courtesy of Edward R. Swoboda) |

In the Orient, a Western purchaser of gems encounters strange difficulties, one of which is the lack of any division between the wholesale and retail trade. In India, the procedure is simple. One chooses a recommended, reliable firm of gem dealers to act as purchasing agents. They sell their own material and are familiar with the entire market as well. A verbal agreement is made giving them a percentage ranging from two to five percent on all outside purchases made in their offices. Word spreads rapidly that an important purchaser is in town and brokers stand in long lines to show their gems. The prospective purchaser is given the opportunity to examine the merchandise and put aside interesting items, together with the marked asking prices, for further consideration and bargaining. At the end of the day, the gems are examined carefully and leisurely and marked with the offered prices. The following day, the bargaining ensues and those papers of stones are purchased on which a price agreement is reached.

The procedure just described is one used in all Oriental countries except Burma, where it is quite different. Upon arrival in Rangoon, one must immediately seek a reliable man to act as interpreter, broker and agent. This is an important choice, determining in no small measure the future success of the purchaser. In Rangoon, there are many dealers who also own retail stores containing large stocks of gems that have been brought to them by the brokers from the Mogok area. As a rule, there is little material of fine quality in the hands of such dealers.

|

| Maung Myint, gem dealer of Mogok, showing rough ruby and sapphire. (Photo courtesy of Edward R. Swoboda) |

If one desires to engage in gem purchasing with the convenience and comforts of a good hotel and fairly decent food, one can remain in Rangoon and do the best he can with his buying. A few telegrams to Mogok may bring some brokers down to show their gems. However, this is a poor arrangement for trying to buy the finest. The only way to see and buy is to go to the source at Mogok. For this prospect, the broker-agent-interpreter becomes even more important!

Once in Mogok, an entirely new set of problems arises. As mentioned previously, there are about 1200 mines in the area and it is impossible to visit all of them even over a long period of time. Therefore, it is advisable to visit the most important dealers first to ascertain what they have to offer. Most surprising is the reluctance with which stones are shown. It seems that the dealers stall on showing until they learn approximately how much money the would-be purchaser has available. A few good starting purchases go a long way in establishing one’s reputation as a buyer with serious intentions to acquire fine gems. The buyer’s opportunities increase as the rumors spread quickly among all the inhabitants.

Contrary to custom in other Oriental countries, the startling fact revealed during a visit to Mogok is that the women are the gem merchants, rather than the men! The most influential dealers are women who are shrewd, cunning and seemingly able to read the purchaser’s mind instinctively. In some cases, the bargaining may be done by the men, but no deal is ever concluded without the full consent of the women in the household—usually the mother, mother-in-law and wife.

On my first visit to Mogok, my experiences and feelings were mixed—amazing, exasperating, frustrating, instructive and illuminating. My agent and I started out early one morning to begin my purchasing transactions. Our first stop was at the home of the most important dealer in Mogok. After two hours of imbibing the customary cups of coffee and tea, along with much conversation, I became impatient and asked my agent about seeing stones. While studying my face intently, the dealer finally exhibited one stone paper containing a very poor star sapphire. Although I wasn’t at all interested in it, I wanted to be polite and inquired about the price. If I recall correctly, I had already judged $25 to be a fair price. When my agent informed me that it was the equivalent of $500, I almost exploded but casually tossed the stone back to the dealer. I asked to see more stones but was told most politely but firmly that there were no others.

We visited five more dealers that day with similar experiences for me at the home of each. One or two stones would be shown at tremendously exaggerated prices that were completely out of line. Even though I knew that the prices were inflated for bargaining, I thought it would be ridiculous to make offers amounting to perhaps five to ten percent of the asking prices. That evening, I went over the day’s experiences and discussed them with my agent. I must digress for a moment at this point to emphasize that great reverence and respect are accorded to age by all Burmese. Because my agent was a much younger man than I, that instinctive respect for my age prevented him from giving me an immediate analysis of my day’s errors. After long discussion, I finally did gather that it was considered bad form not to make an offer on merchandise for sale, no matter how low. I asked whether my offer of $2 for a stone quoted at $100 would not be considered insulting. He assured me that any offer would be graciously received as a compliment to the gemstones, but the eventual selling price would depend on the buyer’s patience and bargaining abilities. Time is of no importance in the Orient and long, patient bargaining is an essential part of trading there. My agent further explained the high asking prices as an attempt by the dealers to learn the purchaser’s idea of a stone’s worth. Apparently, “Let the buyer beware” is the slogan!

It took me a while to assimilate this information and try to act accordingly, since it was so different from our way of conducting business. However, I knew that I must follow my agent’s advice in order to make progress. The next morning, we started out again to another dealer. After the usual long-drawn-out preliminaries of coffee, tea and conversation, I was at last shown a fine gem sapphire weighing six carats for the asking price of $3,000. After careful examination, I decided that I could pay $600 for it and asked my agent to offer $300 giving myself enough leeway for the expected bargaining. Although I couldn’t understand the ensuing conversation, I saw the dealer’s smile express appreciation for the offer. He said “Quarre,” which I had learned means, “Too far apart.” I instructed my agent to tell him that he was asking much more than the stone was worth, and that I would raise my offer a bit if he would come down. The next price asked was $1,000, already a two-thirds reduction! I had my first feeling that gem buying in Mogok might eventually prove successful. I raised my first offer by $100, and he went down another $100. Whereupon my agent suggested that we let the dealer think it over and we would return the next day. The following morning, I requested the lowest price and was told that the very lowest was $700, “Take it or leave it,” My final offer was $600, which was accepted, leaving me in a much more cheerful frame of mind about the entire situation. With my newly acquired education, I was able to make many satisfactory purchases.

After a week, word had spread that I was a good purchaser who paid high prices. Brokers came with gems from many dealers we hadn’t visited, and prospects for a most successful purchasing trip increased day by day. In the process, I slowly became aware of an important factor in the economic life of the miners. Their living conditions are most primitive, requiring an infinitesimal sum of money for all their needs. The most prosperous family spends no more than a thousand dollars a year for all living expenses. As a result, their wealth is measured in terms of the quantity of their stocks of gems. After a dealer sells enough material to provide for his needs for a long time, he is no longer interested in selling. The following experience is a good example. I found a miner with twenty pieces of rough peridot which interested me greatly. He simply refused to sell them because he didn’t want any more money until after the Burmese New Year, three months hence. My agent’s and my persuasion were of no avail. He didn’t need the money and wouldn’t sell until he did, regardless of the possibility of receiving less at a later date. He was quite positive that prices would not go down, since all the miners and dealers were learning that prices were continually rising—which also made for reluctance in selling. They believe it is the better part of wisdom to hold their gems.

The only saving factor in the whole situation is the great devotion to Buddhism practiced by these people, coupled with each one’s desire to outdo the other in the building of magnificent pagodas and temples. Such a purpose on the part of any dealer greatly facilitates business negotiations! Whereas their personal living standards are so low, they do not hesitate to spend enormous sums of money, sometimes as much as $100,000, to build beautiful temples and pagodas—and with modern sanitary facilities so conspicuously absent in their own homes.

Every dealer claims exclusive connections with certain miners to supply him only with their rough stones. Of late, however, the miners have been learning that they have not been receiving full prices and that the dealers have been taking advantage of them. Consequently, they offer their gems to more than one dealer and accept the highest offers for their rough, thus placing the dealers in a highly competitive position. It is extremely difficult to determine the yield from a rough piece of sapphire or ruby, thus making it a really speculative business. The dealers suffer much loss when the rough proves disappointing after cutting.

Alternating in the villages of Mogok and Kyatpyin, there is a bazaar held every five days where the populace buys its supplies of groceries and vegetables. Miners and gem dealers also contribute to this colorful event. Dealers are always recognized by the umbrellas they carry at all times—their badge of office, as it were! Individual miners offer them rough material. My only purchase in a market place was a lot of rough rubies for which the miner began by asking $1000 and after much bargaining accepted my offer of $1.

An amusing purchase I made was at the site of a one-man controlled ditch. This miner showed me a rough piece of ruby that displayed very strong asterism. After my expression of interest, the customary bargaining began. Before long, we had a group of men, women and children surrounding us and enjoying the proceedings. When I finally completed my purchase, the people standing around claimed a commission from me, saying they were all brokers in the deal. It was said good naturedly and with much laughter. I settled the matter by giving the brokerage fee to a few of the smallest children, and my decision was applauded as a wise man.

For many years, rumors have been circulating that the Mogok area is being worked out and will soon stop yielding any gems. My observations have convinced me that mining there will flourish for an indefinite period, and that huge quantities of gemstones worth many millions of dollars are still in the hands of the dealers. I learned that many of them have had gems in their possession for almost half a century. To illustrate, I am thinking of an eighty-two-year-old man I visited. He dreams away the days with his opium pipe and is loath to part with any of his gems. The dealers in Mogok have been unsuccessful in their attempts to buy one of them. Because my agent’s mother was a friend of the old man, I thought I had a good starting point in my quest. We visited one morning and found the old man squatting in a corner smoking his pipe. For four hours, talk flowed back and forth without any reference to business—we were enjoying a social visit. Finally, the conversation veered to the topic of gems and, most fortunately for me, the name of Albert Ramsay was mentioned. It seems that when he was a youngster, the old man had worked for Mr. Ramsay and thought very highly of him. When my agent informed him that I had known Mr. Ramsay (since we had been located in the same office building in New York), the old man declared that any friend of Mr. Ramsay’s was a friend of his; and, eventually, he decided to show me a few of his gemstones. He never exhibited more than one stone at a time. After each deal was concluded, he would disappear into a little cubicle covered by a curtain and emerge with another stone. How I wished I could peek at the treasure I knew was hidden behind that curtain! Rumor had it that the old man’s stock of gems was worth more than a million dollars and dated back to the time of the Ruby Company, which had ceased activities in 1922.

Almost without exception, in every purchase I made, the starting price asked was at least ten times higher than the actual value. Only once was I offered stones at a price I thought they were worth and was willing to pay. However, that willingness almost cost me my reputation as a gem merchant! It was a box of spinels of fine quality for which the dealer asked $300, a price I considered fair and agreed to pay. I shall never forget his expression and the change in him at my ready acquiescence. He turned pale and told my agent I must be a smart one who was trying to take advantage of a poor, simple dealer. He threatened to tell the other dealers I couldn’t be trusted; and my agent and I were really in a dilemma. I thought fast and said to my agent that the offer need not be accepted, at the same time passing the box of spinels back to him. My agent then made the proper move. He took the blame in translating incorrectly, saying I had merely repeated the dealer’s statement of price. My agent whispered to me to make an offer of $150, which I did. After some bargaining, I bought the spinels for $200, absolved of all blame and $100 to the good!

As mentioned previously, the women are the bosses of the gem trade in Mogok. They have the final decision in all transactions involving the larger and more important stones, but they do consult their men, who are in partnership with them in such deals. However, the men have nothing to do with the trading in stones of small sizes. Such business is exclusively the province of the Mogok women and a lucrative one it is. Women throughout Burma wear jewel studs in their blouses and other apparel and are very fond of gemstones mounted in bracelets, earrings, pins and necklaces. A number of manufacturing jewelers in Mogok make attractive well-designed pieces in 22-karat gold. The women gem dealers consider the trading in small stones their bread-and-butter business; but from my own observations, I would say that it keeps them in cake, too! It is a steady, profitable, year-round business.