Tsavorite from Kenya

Tsavorite by Peter Bancroft

Lualenyi Mine, Voi, Kenya

Editor’s Note: We are pleased to reprint this selection from Peter Bancroft’s classic book, Gem and Crystal Treasures (1984) Western Enterprises/Mineralogical Record, Fallbrook, CA, 488 pp.

|

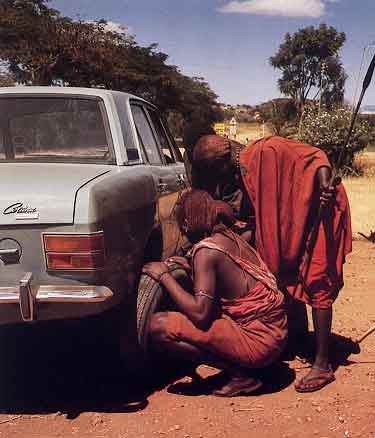

The great Tsavo plain stretches in all directions untouched by man except for the winding scar of a road connecting Kenya’s port city of Mombasa with the inland capital, Nairobi. A few tiny villages of the pastoral Masai people dot the land, but that is all. Oryx, gazelle, springbok, giraffe, and buffalo graze, always alert for carnivores. Migrating herds of zebra and wildebeest cast swirling dust clouds into the sky. And in the background rises perennially snowcapped Mt. Kilimanjaro, Africa’s tallest peak.

Across the border in Tanzania, the first of a series of gem mines was discovered in 1967. Ruby was found in the Matabatu Hills; gem zoisite (tanzanite) appeared near the Usumburu Mountains and chrysoprase on Hanety Hill. (garnets, rubies, and sapphires were screened from gravels in the Umba River. Quantities of grossular garnets of every shade of yellow, green, tan, and brown were found in Lala Taima.

Successful miners like John Saul and Peter Morgan became convinced that gemstone occurrences were not necessarily confined to the Tanzanian side of the border. Precambrian metamorphic graphite-bearing gneisses, similar to those commonly associated with gem deposits in Tanzania, were found in the hills and low mountains of southeastern Kenya.

|

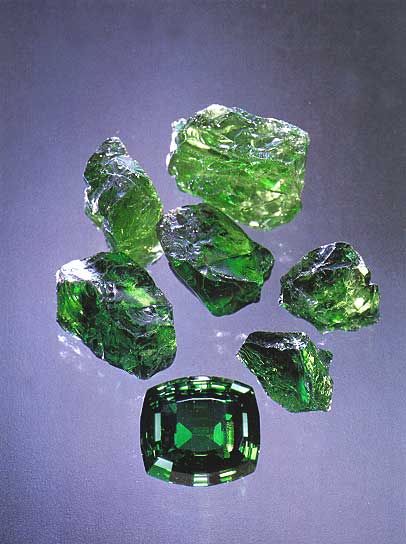

| Green vanadium grossular. Size: Cut stone - 7.59 carats. Locality: Lualenyi mine. Collection: Pala International. Photo: Harold and Erica Van Pelt |

Working independently, Saul and Morgan sent out prospecting teams in search of gems. Masai and Kikuu tribesmen who knew the country well joined the teams. Morgan and his African partner, Kimani, moved into the Mgama Mountains. Search parties spread out to examine float in canyon bottoms and outcrops in the draws. At times they moved roots, dug under clumps of grass, and dislodged bushes. Nothing was overlooked. One day one of the prospectors carried back to camp some green grossular (garnet) he had found in the bottom of the ravine. Early the next morning, Morgan and Kimani followed their guide up to the spot of discovery. Soon other float grossular chips were traced to beds of graphite schist where specks of green grossular glistened in the dull rocks. A major gemstone discovery had been made.

|

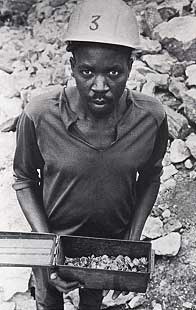

| Metal “safe” half full of green grossular. Photo: William Larson |

The new green grossular mine stands on the southwestern portion of Kide Hill, a part of the Taita Hills district. A road was bulldozed due north to connect with the Mombasa-Nairobi highway. Trees were downed for mine timber after exploratory digging indicated the best portion of the deposit dipped steeply into the hill. A tent camp was set up under trees on an adjoining hillock. An aging but wise 70-year-old African, Mezee Adam, became chief mine engineer; 30 Masai were employed as miners and the recovery of gems was under way. Dogs patrolled a fence surrounding the property from within, though these animals were shortlived as marauding lions negotiated the fence in search of prey.

Mining here was tedious business. The inclined shaft reached a depth of 137 meters, and lines of miners shoveled material up the dimly lit passage from man to man until the loose rock reached the surface. The aggregate was screened by hand and green stones were dropped through a slot in a small iron "safe" secured with a padlock.

The first kilogram of green grossular was accumulated in 1973 and taken to Nairobi. When the lot was poured onto a bathroom scale, William Larson, owner of Pala International, made the first large purchase of Kenya green grossular.

Laboratory tests by Edward Gübelin and Max Weibel in Switzerland proved the grass-green stone to be colored by vanadium. Though not distinct enough to be considered a new species, this was obviously a new variety of garnet quite different from the yellow-green demantoid found in Italy and the Soviet Union. In order to enhance merchandising, the gems received the varietal name tsavorite, after the Tsavo area in which they occur.

|

| Masai warriors change author’s tire. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

Green grossular, a very beautiful stone, has features that surpass those of the emerald. The green garnet has a much higher index of refraction, which results in superior brilliance, tends to greater transparency, and occurs with fewer inclusions. Green grossular is extremely rare, and fine stones of over 5 carats are considered collector’s items. Gübelin owns one good crystal and Herman Bank of Idar-Oberstein, West Germany, owns another.

|

| Main camp at the Lualenyi mine, 1975. Photo: William Larson |

The green gem usually occurs in shattered sections of large porphyroblasts, and attempts to salvage anything resembling a complete crystal of display quality have been nearly fruitless. Much material is unsuitable for gems, which means that grading or marketing the rough requires great skill.

|

| Foreman Mezee Adam (white hat) greets visitors at mine portal. Photo: William Larson |

The largest known faceted green grossulars, reported to weigh more than 30 carats, are usually flawed and therefore are not too attractive. The largest fine quality stone known is a nearly flawless 16.67-carat emerald-cut stone in Richard Webster’s collection.

Spurred on by the discoveries, John Saul (who had witnessed the first sale) redoubled his efforts to discover new commercial gem deposits. In 1974, a bag of small crude reddish corundum crystals was brought to his office. Tracing them to a hill within the Tsavo Game Preserve, Saul began mining. He was unprepared for the extraordinary successes as well as inordinate degrees of intrigue that dogged his venture.

|

| Young men sift for garnets. Photo: William Larson |

Saul’s partner, James Miller, supervised mining activities and the removal of hundreds of kilograms of ruby corundum. A small but important percentage was facet-grade gem ruby, the first to be found in Africa. Colors ranged from hot pink to deep red, and some material faceted into gemstones weighing an amazing 10 carats.

|

| Cheetah with cub in veld near Voi. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

Unfortunately, problems involving mining rights led to claim jumping and friction between Saul and Jomo Kenyatta, then president of Kenya. The mine was abandoned and is not being worked today.

|

| Jeanne Larson admires green gems at the Lualenyi, 1979. Photo: William Larson |

|

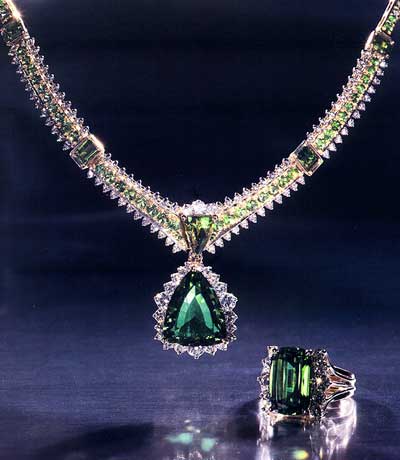

| Green grossular (tsavorite) and diamonds Size: pendant stone 10.7 carats. Locality: Lualenyi mine. Collection: A.H. Stange. Photo: Harold and Erica Van Pelt |

|

About the author. Dr. Peter Bancroft was Marketing Director of Pala International in the mid-1970s. He is also the author of The World’s Finest Minerals and Crystals and has written for many publications in Europe, Australia and the United States. Dr. Bancroft is a well-known lecturer on mines, minerals and gemstones.

In contrast to many “armchair authors” who merely recycle what has appeared in other books, Dr. Bancroft has spent years traveling the world like a modern-day Herodotus, visiting hundreds of remote and fascinating mineral and gem deposits, and interviewing miners and local inhabitants. Bancroft has uncovered a wide range of information, some of it never before published. This and his extensive knowledge of the literature have combined to produce an authoritative and highly readable text.

Although many fine specimens reside in public collections such as the Smithsonian Institution and the British Museum, Bancroft has searched further through a vast number of private collections worldwide in order to assemble the suite of magnificent photographs found in Gem and Crystal Treasures. Many specimens in these collections are rarely if ever available for public view.

Dr. Bancroft has done graduate work in geology at the University of Southern California, The University of California at Santa Barbara, and at Stanford University. His doctorate, in Education Administration, is from Colorado State University. During his long professional career he has served as teacher, principal, and superintendent of schools in California; as a White House consultant on education, as a professional photographer; as a gemstone buyer, as Curator of Mineralogy at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History; and as Director of Collections for the San Diego Gem and Mineral Society.

His personal mineral and crystal collection has won state and national honors. In 1984 he was selected as an Honorary Awardee for the American Federation of Mineral Societies’ Scholarship Foundation.

Dr. Bancroft’s son, Edward, has a collection that can be seen in the Dept. of Geological Sciences at the University of California at Santa Barbara. A beautiful introduction is online at: The Bancroft Collection.

Today, Peter Bancroft resides with his wife Virginia in Fallbrook, CA. Those wishing to correspond with him can contact him at:

Dr. Peter Bancroft

3538 Oak Cliff Drive

Fallbrook, CA 92028

USA

|

Palagems.com Tsavorite Garnet Buying Guide Introduction/Name. Tsavorite is the name given to the rich green variety of grossular garnet. The gem was first discovered in Tanzania in 1967 by Campbell Bridges. In 1970, Bridges also discovered gem tsavorite in Kenya’s Taita/Taveta district. The name “tsavorite” was coined in 1974 by Campbell Bridges and Tiffany’s Henry Platt and is derived from Kenya’s Tsavo National Park, which lies adjacent to rich deposits of the gem. Color. While the color of tsavorite never equals that of the finest emerald, an emerald-green is the ideal. The color should be as intense as possible, without being overly dark or yellowish green. The color of tsavorite is believed to be due to vanadium, at times with a trace of chromium. Lighting. Tsavorite garnet generally looks best under daylight. Incandescent light makes it appear slightly more yellowish green. Clarity. In terms of clarity, tsavorite is relatively clean. Thus when buying one should expect eye-clean or near-eye-clean stones. Cut. In the market, tsavorites are found in a variety of shapes and cutting styles. Ovals and cushions are the most common, but rounds are also seen, as are other shapes, such as emerald cuts, trillions, etc. Cabochon-cut tsavorites are not often seen. Prices. Tsavorite is among the most expensive of all garnets, with prices similar to those fetched by fine demantoid (the other green garnet). But like all gem materials, low-quality (i.e., non-gem quality) pieces may be available for a few dollars per carat. Such stones are generally not clean enough to facet. Prices for tsavorite vary greatly according to size and quality. At the top retail end, they may reach as much as US$8,000 per carat. Stone Sizes. Tsavorite is rare in faceted stones above 7–8 cts. Fine tsavorites above 20 carats can be considered world-class pieces. Most stones tend to be less than 3 cts. Sources. The original locality for tsavorite was Kenya’s Tsavo National Park, but today important deposits of gem tsavorite have also been found in Tanzania’s Lindi Province. Enhancements. Tsavorite is one of the few colored gems that is not normally subject to any type of enhancement. Imitations. Tsavorite garnet has never been synthesized, but a number of imitations exist. These include green glass and green YAG. Green glass is also common at the mines in various rough forms.

Properties of Tsavorite Garnet

|